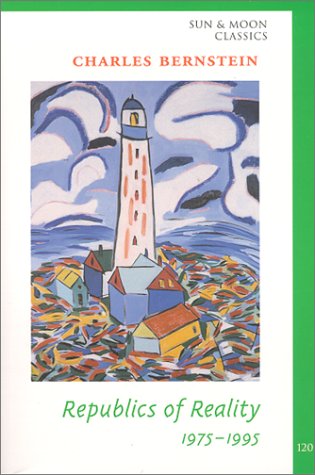

REPUBLICS OF REALITY: 1975-1995  / Charles Bernstein

/ Charles Bernstein

Order direct:

paper &pdf

Proquest digital (each poem as separate file): log in via research library

Sun & Moon Press

376 pages

Published in 2000

REPUBLICS OF REALITY: 1975-1995 contains

eight out-of-print books and one new sequence:

Parsing (1976)

Shade (1978)

Senses of Responsibility (1979)

Poetic Justice (1979)

The Occurrence of Tune (1981)

Stigma (1981)

Resistance (1983)

The Absent Father in "Dumbo" (1990)

& a previously unpublished set: Residual Rubbernecking (1995)

From the March 27, 2000 issue of Publisher's Weekly:

* review: book of "outstanding quality":

"At once the most paradoxically controversial and popular,

accessible and most difficult of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets, Bernstein

is also the writer of that group who strove early on to experiment

with the extremes of its newly minted methods. Whether highlighting

the synaesthesis of the word in its isolation or in the plain

phrase as it operates in daily life to convey our most banal

thoughts, this collection of long out-of-print chapbooks -- none

of these poems has appeared in any of Bernstein's many break-

through volumes, such as Islets/Irriations (1993) or Dark City (1994)

-- provides a unique overview of his career, and adds to the

range of his impressive canon of major and minor works. The first

poem from the 1976 volume PARSING titled "Sentences," will surprise anyone expecting text-over-speech, as it is practically a litany of anxieties, attitudes and stuttering intensities. This attention to spoken language makes such dense works as "Poem" (from

1978's Shade) both welcoming and discomforting, expressionistically cinematic but not without its moments of eye-wink satiric narrative. In the short poems collected in The

Absent Father in "Dumbo" and Residual Rubbernecking,

Bernstein takes the project far from the austere fragments of

the early works and deep into a purposely "purple" and unbeautiful lyricism: "Such mortal slurp to strain this sprawl went droopy/ Gadzooks it seems would bend these slopes in girth/None trailing failed to hear the ship looks loopey/Who's seen it nailed uptight right at its berth." Bernstein always manages to find the furthest reaches of any norms of "good taste" (be

it mainstream or avant-garde), creating a poetics that reveals

the social codes hiding behind all the poetry's tropes and forms.

Though many of the latter poems here seem unfocused and minor

compared to the fabulous and ambitious early chapbooks, the volume

as a whole presents as many promises as it does relevant problems,

as many beauties as it does strange new imaginings."

Paul Quinn on Republics of Reality in PN Review (2000)

Boston Review: Three microreviews of Republics of Reality by Ethan Paquin, John Palattella, David Kellog

Patrick Pritchett on Republics of Reality in Rain Taxi

Susan Schultz on Republics of Reality in Verse (18:2&3,2001)

Brian

Kim Stefans (ouncut version f Publisher's Weekly review)

Allen Mozek, on Republics of Reality at For the Birds blog (Dec. 1, 2009)

From the May 7, 2000 issue The Buffalo News

A strong focus on the language

By R.D. POHL

Special to The Buffalo News 5/7/00

"It's not my/ business to describe/ anything. The only/ report is the/ discharge of/ words called/ to account for their slurs," writes Charles Bernstein in "Have Pen, Will Travel," one of the concluding poems in "Republics of Reality: 1975-1995," his latest collection of work published just last week by Sun and Moon Press.

Description of a perceived world "out there" has never been the principal concern of Bernstein's poetry, which he prefers to call "polyreferential" with respect to the way its language engages a range of possible readings. Instead his focus has been on the particularity of language itself, its sheer physicality and "animalady" (a Bernstein coinage) as well as how it colors, shapes, and orders how we experience and think about the world.

"Love of language," he writes in this volume's "Palukaville," "excludes its reduction to a scientifically managed system of reference in which all is expediency and truth is nowhere."

"Republics of Reality" consists of a compilation of eight of Bernstein's previously published chapbooks or limited edition publications now long out-of-print, plus a ninth section (called "Residual Rubbernecking") which appears here for the first time in book form.

Despite weighing in at a hefty 374 pages, this volume represents only a portion of Bernstein's total oeuvre during the period in question. Not included are all the poems contained in his longer, better known collections with larger publishers (particularly Sun and Moon Press) including the volumes "The Sophist" (1987), "Rough Trades" (1991) and "Dark City" (1994) upon which rest his current reputation as perhaps this country's leading advocate for literary innovation and a language-centered approach to poetics.

But for readers who know Bernstein principally as a writer-critic, teacher and scholar (he is the David Gray Professor of Poetry and Letters at the University at Buffalo and directs UB's Poetics Program), this volume presents a fascinating overview of the first two decades of his prolific career, particularly the early work which played such an influential role in the evolution of so-called "language" poetry in North America. (Bernstein co-founded and co-edited the magazine L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E with colleague Bruce Andrews from 1978 to 1981.)

From the minimalist, serialist approach of "Sentences" in his first collection "Parsing" (a remarkable poem that retains a certain vestigial narrative thread: it's about sickness, insecurity, and fear masquerading as boredom) to the more radical experiments with sense, syntax and spelling in prose and mixed forms in the collections "Shade," "Poetic Justice" and "The Occurrence of Tune," one can almost discern an exploratory arc in Bernstein's work. If at first he appears to whimsically deconstruct most of the familiar elements of poetic form, he subsequently relocates the presence of language in a poem's most basic, irreducible phonemes.

Several of the poems in "Poetic Justice" engage in a high playfulness that suggests new ways of thinking about how a poem can be organized. "Electric" gets startling comic effects out of punning, clever wordplay and improvised upper and lower case shifting: the typographical equivalent of a malfunctioning Caps Lock key on a typewriter. "Azoot D' Puund" is written in an invented language that looks like a hybrid of Chaucerian English (is the reference to Ezra Pound?) and Afrikaans.

One of more notable surprises of reading through this volume, however, is the degree to which Bernstein's writing since mid-1980s has gravitated towards recognizably lyrical forms. At least in the work represented here (the collections including "Resistance" (1983), "The Absent Father in "Dumbo' " (1990) and "Residual Rubbernecking") he has consistently introduced familiar rhythms and even occasional rhyme schemes into his increasingly musical work.

This is not to suggest that his work is any less subversive, however, since the shift seems designed at least in part for comic and satirical purposes. Nor has his syntax become any more specifically referential. Reading or listening to one of Bernstein's poems still reminds one of Ludwig Wittgenstein's famous remark about language occasionally "going out on holiday": the rules of grammar and reference seem a bit relaxed, but everyone's having a ball.

Still, when he begins a poem like "Bulge" ("The reward for/ love is not/ love, any more/ than the reward/ for disobedience/ is grace. What/ chains these/ conditions severs/ semblance of/ a hand, two/ fists, in pre-emptive/ embrace with/ collusion") even if the sense of the poem is complex, disjunctive, and replete with possible meanings, its rhythm and form evoke lyrical feeling.

Contrast this to a decidedly anti-lyrical excerpt from "The Taste is What Counts" from Bernstein's "Poetic Justice" (1979): "More than I pretend, choppiness, its mass, a revolt against it. Complication beyond the box they require pervades like the world it makes. The purposiveness of the sensations a clear mirror. Glimpse immediately flashing formed with a passing knowledge that becomes your whole life reflected. Still empty the waves turning, movement to become an opacity as lap or imprint." In "Autonomy is Jeopardy," Bernstein, who does not typically write for a specific voice (and indeed rejects the idea of constructing an "authentic" narrative voice in principle) creates an alter ego whose fears correspond to those of the reader, and quite possibly to those of the poet himself. "Poetry scares me," he writes, "I/ mean its virtual (or ventriloquized)/ anonymity no protection, no/ bulwark to accompany its pervasive/ purposivelessness, it accretive/ acceleration into what may or / may not swell. Eyes demand/ counting, the nowhere seen everywhere/ behaved voicelessness everyone is clawing/ to get a piece of. Shudder/ all you want it won't/ make it come any faster/ last any longer."

Order direct:

paper & digital