The composer Brian Ferneyhough and the librettist Charles Bernstein call "Shadowtime," their new work based on the writings and life of the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin, a "thought opera." Among operatic types, that's a new one.

"Shadowtime," which had its premiere at the Munich Biennale in 2004, is a work of uncompromising complexity. By calling it a thought opera, Mr. Ferneyhough, a high modernist British composer, and Mr. Bernstein, a noted American poet, are doing more than signaling that the work explores the intellectual issues Benjamin dealt with, including the nature of time, language, melancholy and dialectical materiality. They are implying that the audience must put aside traditional notions of musical drama - of storytelling, narrative and character development - and enter an intellectual journey.

A large audience presumably willing to do just that arrived at the Rose Theater on Thursday night when the Lincoln Center Festival presented the North American premiere of "Shadowtime." But halfway through this work, which lasts two hours and 15 minutes without intermission, a steady trickle of audience members began leaving. While I was intrigued by "Shadowtime," which bracingly challenges the very notions of what opera can be, I sympathized with those who gave up on the work.

The opera begins on Sept. 26, 1940, the last night of Benjamin's life. Ailing and in flight from Nazi Germany, Benjamin and a traveling companion arrived in a Spanish town near the French border en route to America and freedom. When they were turned back from France, though, Benjamin committed suicide. These events are loosely depicted in the opening scene. The subsequent six scenes are metaphysical explorations of Benjamin's philosophy and spiritual states, as he relives his life and confronts his ghosts.

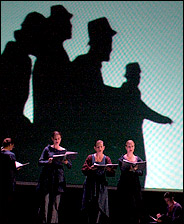

But the opera seems intentionally obscure and needlessly convoluted. It relies on the surreal images of the director Frédéric Fisbach's production and, of course, the subliminal pull of Mr. Ferneyhough's music to make the drama, such as is it, emotional and resonant.

For all its ingenuity, Mr. Ferneyhough's music, scored for diverse chamber orchestra and chorus, becomes exasperating. What makes his style engaging, but also difficult, is his penchant for layering events. In the instrumental prologue, as a gaggle of instruments snarl and dart about in barely contained frenzy, other instruments - lacy melodies in the winds, a ruminative cello line - slowly thread through the din of atonality. Amazingly, though, Mr. Ferneyhough writes with uncanny clarity even in the densest moments.

Yet when the textures thin for long stretches of delicate and pensive music, the multiplicity of musical events keeps right on going. Almost never does Mr. Ferneyhough give listeners a break - say, a passage where all the instruments play in unison or an episode of sublime harmony, the kinds of moments that ravish you in the operas of earlier modernists like Berg and Messiaen.

In one scene, called "Shadow Play," which depicts the descent of Benjamin into the underworld, a solo pianist and reciter, meant to be a Liberace-type entertainer, plays a violently difficult and mesmerizing piano work of nearly 20 minutes while reciting a text that mixes droll philosophical questions with gibberish. As a major work on a solo piano recital, this piece would be a knockout, especially as performed here by the formidable pianist and actor Nicolas Hodges. But as a scene in an opera it seemed artificially inserted.

"Shadowtime" also challenges the traditional role of words in opera. From the opening scene, phrases of the libretto are sung and spoken simultaneously, often layered as thickly as the instruments in the orchestra. There is not even a pretense that the words will be audible to the audience as sung from the stage. Essential lines are projected in supertitles. The text becomes just another element of musical fodder.

Heading the impressive cast was the earthy bass Ekkehard Abele, who portrayed Benjamin as a tall, gaunt, tormented man in a crew cut. But his role curiously diminishes as the opera continues. The choristers from the Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart and the musicians from the Nieuw Ensemble Amsterdam, brilliantly conducted by Jurjen Hempel, seemed engrossed by this work. The festival deserves much credit for courageously presenting it.

In a program note, Mr. Ferneyhough writes that listeners must "let go of a fixed notion of what constitutes musical form" to understand "Shadowtime." Maybe so. But that comes very close to saying that if you don't like my opera it's your fault.