Jeaveen Nowak

Eng 339: HUIDOBRO:

Final Exam Review Sheet

Presentation : 16 June 2003

b. Santiago, Chile, 1893-d. Santiago, Chile, 1948 School: Attended Colegio San Ignacio (Jesuit College) Influences: Apollinaire, Juan Gray, Picasso

VICENTE HUIDOBRO

BACKGROUND:

Vicente Huidobro was born on January 10, 1893 to an aristocratic family. A witch predicted that he would either be a thief or a great man when he was very young (DeCosta, 2). Wondering which stance he should take, Huidobro strove to be successful in hopes that he would end up the latter of the two. Raised Catholic, Huidobro attended Jesuit schools. One of which had been an exclusive college in Santiago, Colegio San Ignacio. He describes his experience in these schools as encouraging what he calls his “first disillusionment,” “that priests were actually kind people,” (DeCosta, 2). Finding that priests were really “cranky, strict, easily angered and eager to punish,” (DeCosta, 2) he had come away from such schools with a bitter taste in his mouth. Publishing all of this in a manuscript, entitled Yo, the publication had been burned and banned.

It was then that he decided to make his way to Paris, France at the young age of 20. With him, he brought his wife of two years, Manuela Portales Bello, and children. In Europe, Huidobro had established many small magazines, one of which had been Nord-Sud, or “North-South,” with Paul Reverdy in which he propagandized his newly found Creationist movement. There he had also been strongly influenced by the Cubist movement founded in part by Dada. Among others, he had also been in touch with in Europe, Guillaume Apollinaire, Picasso, and Reverdy, and Juan Gris, were among the ranks. Experimentalism had influenced him greatly as he painted his poems, manipulated language in fantastical ways, and even assisted the war effort with many publications in small magazines that he had established. He was absorbed, at a young age, by his experiences in France, and later Madrid, where he had flocked to in the early 1930s to argue with surrealists and “every major poet of his time,” (DeCosta, 3). He had also been an advocate for Irish Independence in 1923, publishing in Finis Britannia. This stint reportedly brought on bombings of his home and awarded him beatings from the angry British. He had also reportedly been kidnapped (DeCosta, 2).

Huidobro with Juan Larrea,

He returned to Chile in 1925, where he ran for Presidency and lost, after having attacked the establishment for what he calls “crimes against the nation,” (DeCosta, 2). Losing the election to a bureaucrat, he later returned to Europe to continue with the Ultraist movement, a Spanish offshoot of Creationism in Madrid. Huidobro, always searching for what is new and wanting to be on the front lines, never followed through for very long with Creationism. Huidobro, wanting to be at the forefront of everything, had also become a war correspondent for the Second World War. He had written many previous publications for the First World War and Spanish Civil War, siding with the Republican effort. Not only had Huidobro thrived at shaking people up, but he also experimented a great deal with language. He wanted to add to nature and literature as opposed to copying it like the realists, allowing the unconscious to guide language, like the surrealists, and writing about skyscrapers like the futurists had in his day. He wanted to be different. One of his opponents at the time, Pablo Neruda, describes Huidobro’s poetry and prose as “flawed by his person, his prankish personalism,” (DeCosta, 3). Yet, he goes on to state that his poetry is “a mirror image in which are reflected images of pure delight along with the game of his personal struggle,” (DeCosta, 3). Huidobro’s personal struggle was perhaps with the innovative techniques that he employed. He returned to Santiago in the 1940s. It was there that he had died, just before turning 55, of a stroke and complications from shrapnel wounds from the Second World War. He left behind many publications and scraps of what he had done throughout his career such as: 15 volumes of poetry, including his most famous Altazor, or A Voyage in a Parachute (1919), six novels, two plays, five volumes of essays, and many articles and magazines, including Azul, Creación, Acción, Total, Ombligo, and Vital. At the time of the Creationist movement, he is credited with encouraging Paul Reverdy to establish Nord-Sud, as well as Juan Larrea and Gerardo Diego with Favorables-Paris-Poema, 1922. He writes to Larrea and Diego to “be very tough in accepting contributions so that everyone will want to appear in your company,” (DeCosta. 4). Huidobro encouraged others to have a voice as well. He had also worked in film, among his many career moves. Posthumously, Neruda describes Huidobro, as “consumed by his own flame,” as he had sought to try out many art forms and stir the masses (DeCosta, 4). Perhaps he was, but left behind a legacy that is remembered and carried forth in his native Chile, and stays with us today.

CUBISM (THE AVANT-GARDE):

As Modernism began to take effect in Europe, so did the

Cubist movement that had influenced Huidobro’s later Creationist and Ultraist

movements. Cubism had allowed artists

to experiment with their work in unnatural ways. Cubism, the tactile version of literary Creationism, can be best

defined as a

way of translating objects emotionally through manipulation of the subject

matter. Therefore, various subjects are compiled more for appearance rather

than their closeness to reality. In a

word, this form of art had been more aesthetic. Aestheticism greatly influenced Huidobro’s literature and poetry,

in that he attempted to replicate much of the same work using words. This generated the Creationist

movement. (http://members.lycos.co.uk/cubist_movement/)

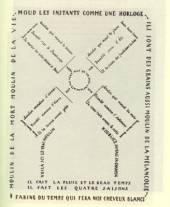

CREATIONISM:

It had been argued at one point in

time as to who founded this movement.

Paul Reverdy is credited with having the idea, yet Huidobro had been a

major advocate of it and used it in his own work. This movement sought to add to nature, rather than copy it. The notion for this movement, and later it’s

Spanish offshoot (Ultraism), centered around putting two conflicting ideas

together, such as “skeleton combs its hair.”

Huidobro, who had been criticized heavily for this as either too

avant-garde, or not enough, sought to play with language to portray an emotion

through its conflicting and fantastical ideas.

His European influences were most responsible for this.