SUSAN HOWE

from The Birth-Mark: Unsettling the Wilderness

in American Literary History. Middletown, CT:

Wesleyan University Press, 1993. EPC Edition © 2005 Susan Howe. Used with permission of the author.

These Flames and Generosities of the Heart

Emily Dickinson and the Illogic of Sumptuary Values

Spirit cannot be moved by Flesh—It must be moved by spirit—

It is strange that the most intangible is the heaviest—but Joy and Gravitation have their own ways. My ways are not your ways—

(L pf44)

An idea of the author Emily Dickinson—her symbolic value and aesthetic function—has been shaped by The Poems of Emily Dickinson; Including variant readings critically compared with all known manuscripts, edited by Thomas H. Johnson and first published by the Belknap Press of Harvard University in 1951, later digested into a one-volume edition, to which I do not refer because of Johnson's further acknowledged editorial emendations. For a long time I believed that this editor had given us the poems as they looked. Nearly forty years later, The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson, edited by R. W. Franklin and again published by the Belknap Press of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, in 1981, and The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson, also edited by R.W. Franklin, in 1986, this time published by the Amherst College Press, show me that in a system of restricted exchange, the subject-creator and her art in its potential gesture were domesticated and occluded by an assumptive privileged Imperative.

* * *

A Concrete Community of Exchange Among Peers

1951: "1860: Alignment of words less regular, letters in a word sometimes diminishing in size toward the end, which gives an uneven effect to the page. No important changes in form" [my italics.] (PED liv).

1986: "Standard typesetting conventions have also been followed in regard to spacing and punctuation. No attempt has been made to indicate the amount of space between words, or between words and punctuation, or to indicate, for example, the length of a dash, its angle, spatial relation to adjoining words or distance from the line of inscription. Dashes of any length are represented by an en dash, spaced on each side. Periods, commas, question marks, ending quotation marks, and the like, have no space preceding them, however situated in the manuscripts. Stray marks have been ignored." (ML 10)

* * *

Fellows

1958: Thomas H. Johnson: Introduction to The Letters of Emily Dickinson.

Since Emily Dickinson's full maturity as a dedicated artist occurred during the span of the Civil War, the most convulsive era of the nation's history, one of course turns to the letters of 1861- 1865, and the years that follow, for her interpretation of events. But the fact is that she did not live in history and held no view of it past or current (L xx).

1986: Ralph W. Franklin: Introduction to The Master Letters.

Dickinson did not write letters as a fictional genre, and these were surely part of a much larger correspondence yet unknown to us. In the earliest one, written when both she and the Master were ill, she is responding to his initiative after a considerable silence. The tone, a little distant but respectful and gracious, claims few prerogatives from their experience, nothing more than the license to be concerned about his health. . . . The other two letters, written a few years later, stand in impassioned contrast to this. . . . In both she defends herself, reviewing their history, asserting her fidelity. She asks what he would do if she came "in white." She pleads to see him. (ML 5)A drop of ink mars the top of the third page [first letter], but it may have come after she had written an awkward predication [my italics] further down the same page:

Each Sabbath on the

sea, makes me count

the Sabbaths, till we

will the

meet on shore – and

whether the hills will look as blue as the

sailors say–This would require obstrusive correction, and what was to have been a final draft became an intermediate one (ML 11).

1951: T. H. Johnson: Introduction to Emily Dickinson's Collected Poems, called "Creating the Poems: The Poet and the Muse."

It would thus appear that when Emily Dickinson was about twenty years old her latent talents were invigorated by a gentle, grave young man [Benjamin Franklin Newton] who taught her how to observe the world. . . . Perhaps during the five years after Newton's death she was trying to fashion verses in a desultory manner. Her muse had left the land and she must await the coming of another. That event occurred in 1858 or 1859 in the person of the Reverend Charles Wadsworth. . . . A volcanic commotion is becoming apparent in the emotional life of Emily Dickinson. . . . Except to her sister Lavinia, who never saw Wadsworth, she talked to no one about him. That fact alone establishes the place he filled in the structure of her emotion. Whereas Newton as muse had awakened her to a sense of her talents, Wadsworth as muse made her a poet. The Philadelphia pastor, now forty-seven, was at the zenith of his mature influence, fifteen years married and the head of a family, an established man of God whose rectitude was unquestioned. . . . By 1870 . . . [t]he crisis in Emily Dickinson's life was over. Though nothing again would wring from her the anguish and the fulfillment of the years 1861-1865, she continued to write verses throughout her life. [my italics] (PED xxi-iv)

1971: Webster's Third New International Dictionary.

VERSE: 3 a (1): metrical language: speech or writing distinguished from ordinary language by its distinctive patterning of sounds and esp. by its more pronounced or elaborate rhythm. (2): metrical writing that is distinguished from poetry esp. by its lower level of intensity and its lack of essential conviction and commitment. <many writers of ~ ~ who have not aimed at writing poetry—T. S. Eliot> (3): POETRY 2<~ ~ that gives immortal youth to mortal maids—W. S. Landor>

4 a (L): a unit of metrical writing larger than a single line: STANZA.

* * *

Circles

In 1985 I wrote a letter to Ralph Franklin, the busy director of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, to suggest that The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson show that after the ninth fascicle (about 1860) she began to break her lines with a consistency that the Johnson edition seemed to have ignored. I was interested because Franklin is currently editing the new Poems of Emily Dickinson: lncluding variant readings critically compared with all known manuscripts for Harvard University Press. I received a curt letter in response. He told me the notebooks were not artistic structures and were not intended for other readers; Dickinson had a long history of sending poems to people—individual poems—that were complete, he said. My suggestion about line breaks depended on an "assumption" that one reads in lines; he asked, "what happens if the form lurking in the mind is the stanza?" [my italics]

* * *

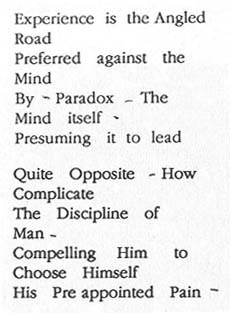

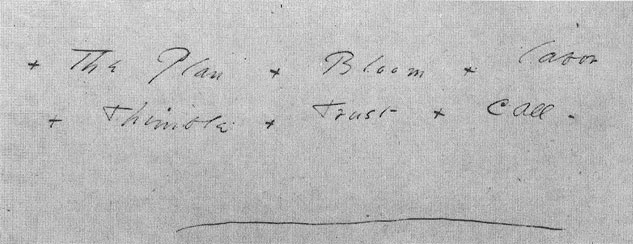

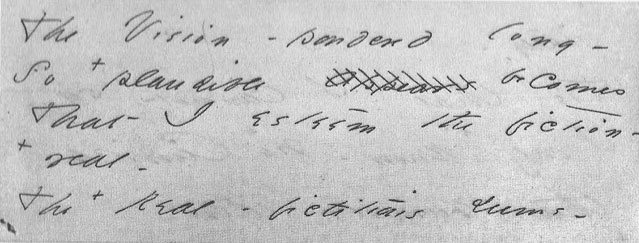

(MBED 2:1020; 53)

Thomas H. Johnson's The Poems of Emily Dickinson did restore the poet's idiosyncratic spelling, punctuation (the famous dashes), and word variants to her poems. At the same time he created the impression that a definitive textual edition could exist. He called his Introduction "Creating the Poems," then gave their creator a male muse-minister. He arranged her "verses" into hymnlike stanzas with little variation in form and no variation of cadence. By choosing a sovereign system for her line endings—his preappointed Plan—he established the constraints of a strained positivity. Copious footnotes, numbers, comparisons, and chronologies mask his authorial role.

(MBED 2:1033; 55)

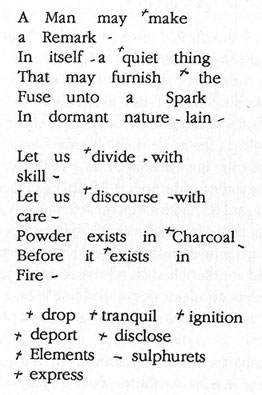

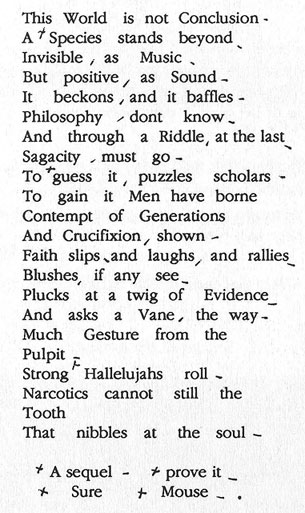

Here is a typographical transcription of Dickinson's manuscript version:

The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson complicate T. H. Johnson's criteria for poetic order.

These lines traced by pencil or in ink on paper were formed by an innovator .

This visible handwritten sequence establishes an enunciative clearing outside intention while obeying intuition's agonistic necessity.

These lines move freely through a notion of series we may happen to cross—ambiguous articulated Place.

At the end of conformity on small sheets of stationery:

(MBED 1: 505; f22)

Deflagration of what was there to say. No message to decode or finally decide. The fascicles have a "halo of wilderness." By continually interweaving expectation and categories they checkmate inscription to become what a reader offers them.

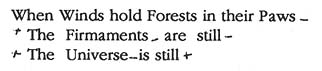

(MBED 2:915; f37)

Use value is a blasphemy. Form and content collapse the assumption of Project and Masterpiece. Free from limitations of genre Language finds true knowledge estranged in it self.

(MBED 2:818; f34)

* * *

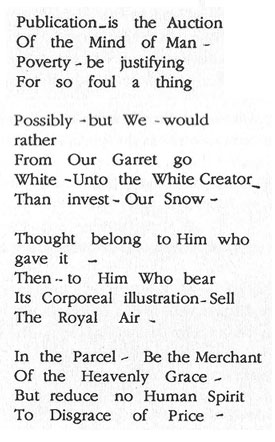

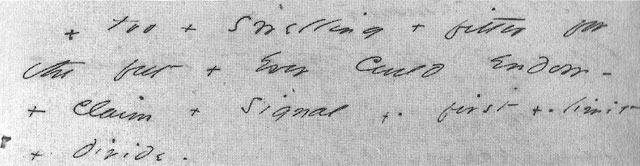

1991: An editor's query. "You need to give the reader some thoughts about making use of the words at the end of the 'poem proper' (in this case, I think, beginning with 'too swelling fitter for'). Are we to attach these words as alternatives to certain words in the 'poem'?; i.e., where does 'too' go? What am I to do with it?"

This is a good question: Thomas Johnson reads these words as alternatives.

1840: Noah Webster: An American Dictionary of the English Language.*

TOO, adv. [Sax, to.]

1. Over: more than enough; noting excess; as, a thing is too long, too short, or too wide; too high; too many; too much.

His will too strong to bend, too proud to learn. Cowley.

2. Likewise; also; in addition.

A courtier and a patriot too Pope

Let those eyes that view

The daring crime, behold the vengeance too. Pope

3. Too, too. repeated, denotes excess emphatically; but this repetition is not in respectable use. [The original application of to, now too, seems to have been to a word signifying a great quantity; as, speaking or giving to much; that is, to a great amount. To was thus used by old authors.] (WD 1159-60)* * *

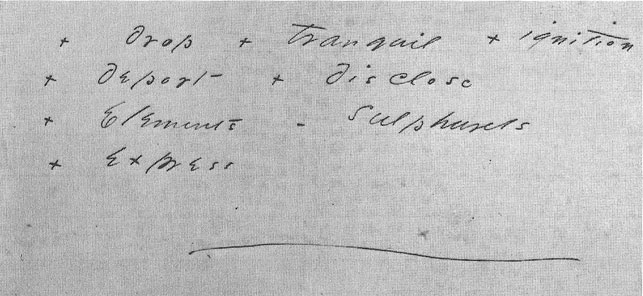

Rearrangement

Much critical and editorial attention has been given to Dickinson's use of capitalization and the dash in her poems and letters; while motivating factors for words and phrases she often added to a "poem proper," sometimes in the margins, sometimes between lines, but most often at the end, have aroused less interest. Since the Johnson edition was published in 1951, it has been a given of Dickinson scholarship that these words represent nothing more than suggested alternates for specific words in the text the poet had frequently marked with a cross.

Ralph Franklin says that after 1861 these possibilities for alternate readings are a part of the structure of the poems she transcribed and bound together, and his edition of The Manuscript Books shows this to have been the case.

After 1861, Dickinson's practice of variation and fragmentation also included line breaks. Unlike Franklin, I believe there is a reason for them.

This space is the poem's space. Letters are sounds we see. Sounds leap to the eye. Word lists, crosses, blanks, and ruptured stanzas are points of contact and displacement. Line breaks and visual contrapuntal stresses represent an athematic compositional intention.

This space is the poet's space. Its demand is her method.

(MBED 2:818; f34)

One of Thomas Johnson's contributions to transmission of the handwritten manuscripts into print was to place these words, sometimes short phrases, at the end of a poem, as Dickinson had done. But he couldn't leave it at that. This textual scholar-editor, probably with the best intentions, matched word to counterword, numbered lines as he had reduplicated them, then exchanged his line numbers for her crosses.

3. True] too |

17. ask] claim |

Emily Dickinson's writing is a premeditated immersion in immediacy.

Codes are confounded and converted. "Authoritative readings" confuse her nonconformity.

In 1991 these manuscripts still represent a Reformation.

* * *

Swelling

NOAH WEBSTER:

SWELL. v.t. To increase the size, bulk, or dimensions of; to cause to rise, dilate, or increase. Rains and dissolving snow swell the rivers in spring, and cause floods. Jordan is swelled by the snows of Mount Libanus (WD 1118).

* * *

A covenant of works

"The flood of her talent is rising" (L 332).

The production of meaning will be brought under the control of social authority.

For T. H. Johnson, R. W. Franklin, and their publishing institution, the Belknap Press of Harvard University, the conventions of print require humilities of caution.

Obedience to tradition. Dress up dissonance. Customary usage. Provoking visual fragmentation will be banished from the body of the "poem proper."

Numbers and word matches will valorize these sensuous visual catastrophes.

Lines will be brought into line without any indication of their actual position.

An editor edits for mistakes. Subdivided in conformity with propriety.

A discreet biographical explanation: unrequited love for a popular minister will consecrate the gesture of this unconverted antinomian who refused to pass her work through proof.

Later the minister will turn into a man called "Master."

R.W. FRANKLIN:

Although there is no evidence the [Master] letters were ever posted (none of the surviving documents would have been in suitable condition), they indicate a long relationship, geographically apart, in which correspondence would have been the primary means of communication (ML 5).

Poems will be called letters and letters will be called poems.

"The tone, a little distant but respectful and gracious, claims few prerogatives." (ML 5)

". . . the Hens

lay finely . . ." (Epigraph to L, part 1, vol. 1)

Now she is her sex for certain for editors picking and choosing for a general reader reading.

NOMINALIST and REALIST

"Into [print] will I grind thee, my bride" (E2 241).

Franklin's facsimile edition of The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson shows some poems with so many lists of words or variants that even Johnson, who was nothing if not methodical, couldn't find numbers for such polyphonic visual complexity.

What if the author went to great care to fit these words onto pages she could have copied over? Left in place, seemingly scattered and random, these words form their own compositional relation.

R.W. EMERSON:

I am very much struck in literature by the appearance that one person wrote all the books; as if the editor of a journal planted his body of reporters in different parts of the field of action, and relieved some by others from time to time; but there is such equality and identity both of judgment and point of view in the narrative that it is plainly the work of one all-seeing, all-hearing gentleman. I looked into Pope's Odyssey yesterday: it is as correct and elegant after our canon of to-day as if it were newly written (E2 232).

Antinomy. A conflict of authority. A contradiction between conclusions that seem equally logical reasonable correct sealed natural necessary

1637: Thomas Dudley at Mrs. Ann Hutchinson's examination by the General Court at Newton:

"What is the scripture she brings?" (AC 338)

An improper poem. Not in respectable use. Another way of reading.

Troubled subject-matter is like troubled water.

* * *

Fire may be raked up in the ashes, though not seen.

Words are only frames. No comfortable conclusion. Letters are scrawls, turnabouts, astonishments, strokes, cuts, masks.

These poems are representations. These manuscripts should be understood as visual productions.

The physical act of copying is a mysterious sensuous expression.

Wrapped in the mirror of the word.

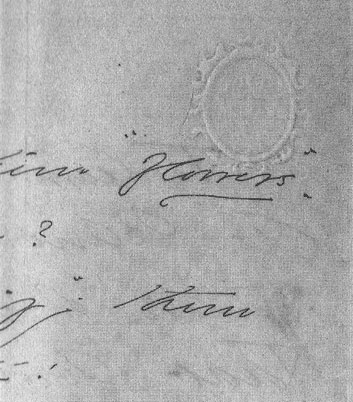

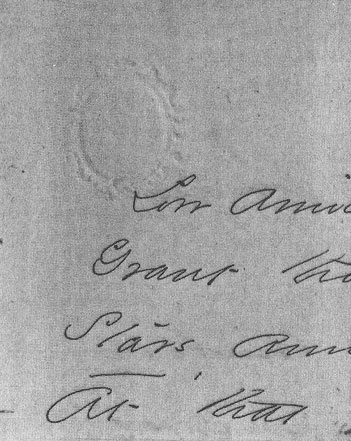

Most often these poems were copied onto sheets of stationery previously folded by the manufacturer. The author paid attention to the smallest physical details of the page. Embossed seals in the corner of recto and verso leaves of paper are part of the fictitious real.

|

basket of flowers C. V. Mills, capitol and, CONGRESS capitol in oval CONGRESS above capitol flower in oval G & T in eight-sided device G. & T. in oval LEE MASS. PARSONS PAPER CO queen's head above L (laid) queen's head above L (wove) WM above double-headed eagle (MBED 2:1411) |

Spaces between letters, dashes, apostrophes, commas, crosses, form networks of signs and discontinuities.

"Train up a Heart in the way it should go and as quick as it can twill depart from it" (L pf115).

Mystery is the content. Intractable expression. Deaf to rules of composition.

What is writing but continuing.

Who knows what needs she has?

The greatest trial is trust.

Fire in the heart overcomes fire without

* * *

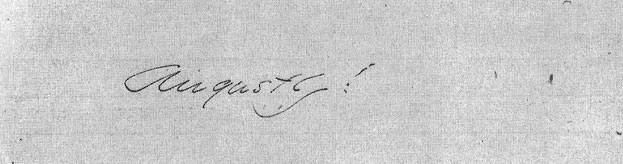

Franklin's notes to set 7 tell us: "On her inventory of the manuscripts obtained from her mother [Mabel Loomis Todd], MTB [Millicent Todd Bingham] recorded a small slip laid inside sheet A 86-¾ bearing only the word 'Augustly!' The paper is wove, cream, and blue-ruled." (MBED 2:1387)

* * *

Disjunct Leaves

Emily Dickinson almost never titled a poem. She titled poems several times.

She drew an ink slash at the end of a poem. Sometimes she didn't.

She seldom used numbers to show where a word or a poem should go. She sometimes used numbers to show where a word or a line should go.

The poems in packets and sets can be read as linked series.

The original order of the packets was broken by her friends and first editors so that even R.W. Franklin—the one scholar, apart from the Curator of Manuscripts, allowed unlimited access to the originals at Harvard University's Houghton Library—can be absolutely sure only of a particular series order for poems on a single folded sheet of stationery.

Maybe the poems in a packet were copied down in random order, and the size of letter paper dictated a series; maybe not.

When she sent her first group of poems to T. W. Higginson, she sent them separately but together.

She chose separate poems from the packets to send to friends.

Sometimes letters are poems with a salutation and signature.

Sometimes poems are letters with a salutation and signature.

If limits disappear where will we find bearings?

What were her intentions for these crosses and word lists?

If we could perfectly restore each packet to its original order, her original impulse would be impossible to decipher. The manuscript books and sets preserve their insubordination. They can be read as events, signals in a pattern, relays, inventions or singular hymnlike stanzas.

T. W. Higginson wrote in his "Preface" to Poems by Emily Dickinson (1890): "The verses of Emily Dickinson belong emphatically to what Emerson long since called 'The Poetry of the Portfolio,'—something produced absolutely without the thought of publication, and solely by way of the writer's own mind. . . . They are here published as they were written, with very few and superficial changes; although it is fair to say the titles have been assigned, almost invariably, by the editors" (P iii-v).

But the poet's manuscript books and sets had already been torn open. Their contents had been sifted, translated, titled, then regrouped under categories called, by her two first editor-"friends": "Life," "Love," "Nature," "Time and Eternity."

* * *

White lines on a white stone

On September 12,1840, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote to Elizabeth Hoar: "My chapter on 'Circles' begins to prosper, and when it is October I shall write like a Latin Father" (E1 433n).

"The one thing which we seek with insatiable desire is to forget ourselves, to be surprised out of our propriety, to lose our sempiternal memory and to do something without knowing how or why; in short to draw a new circle. Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm. The way of life is wonderful; it is by abandonment" (E1 321).

* * *

Overflow

1891 : Twenty years after the event, T. W. Higginson, with Mabel Loomis Todd, the first editor of Emily Dickinson's poetry, recalled one of his two meetings with the poet.

The impression undoubtedly made on me was that of an excess of tension, and of an abnormal life. Perhaps in time I could have got beyond that somewhat overstrained relation which not my will, but her needs had forced upon us. Certainly I should have been most glad to bring it down to the level of simple truth and every-day comradeship; but it was not altogether easy (L 342bn).

TOO. adv. [Sax. to.]

Over; more than enough; noting excess; as, a thing is too long, too short, too wide, too high, too many, too much (WD 1159).

* * *

Coming to Grips with the World

In 1986, Ralph Franklin sent me a copy of The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson, published by the Amherst College Press. Along with The Manuscript Books, this is the most important contribution to Dickinson scholarship I know of. In this edition, Franklin decided on a correct order for the letters, showed facsimiles, and had them set in type on each facing page, with the line breaks as she made them. I wrote him a letter again suggesting that if he broke the lines here according to the original text, he might consider doing the same for the poems. He thanked me for my "immodest" compliments and said he had broken the letters line-for-physical-line only to make reference to the facsimiles easier; if he were editing a book of the letters, he would use run-on treatment, as there is no expected genre form for prose. He told me there is such a form for poetry, and he intended to follow it, rather than accidents of physical line breaks on paper.

* * *

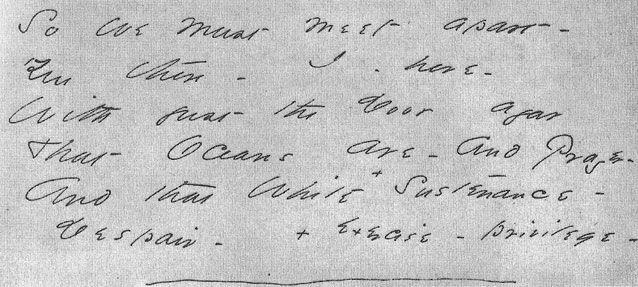

As a poet, I cannot assert that Dickinson composed in stanzas and was careless about line breaks. In the precinct of Poetry, a word, the space around a word, each letter, every mark, silence, or sound volatizes an inner law of form—moves on a rigorous line.

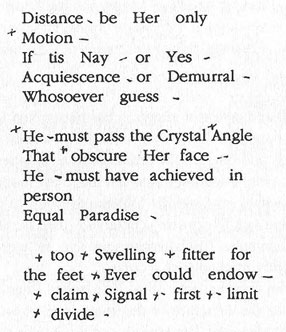

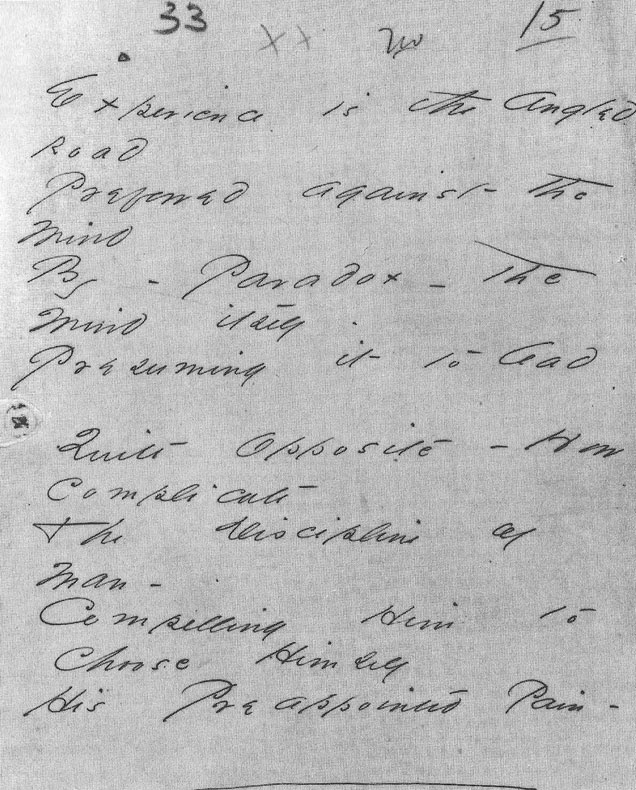

(MBED 2:815; f34)

I wonder at Ralph Franklin's conclusion that these facsimiles are not to be considered as artistic structures.

How can this meticulous editor, whose acute attention to his subject matter has yet to be deciphered in the neutralized reading even her fervent admirers give her, now repress the physical immediacy of these spiritual improvisations he has brought to light?

(MBED 2:1047; S5)

Simple reflection should cast light on the inauthentic nostalgia of A Portrait of the Artist as a Woman, isolated from historical consciousness, killing time for no reason but arbitrary convenience, as she composes, transcribes, and arranges into notebooks or sets over a thousand visionary works.

During her lifetime this writer refused to collaborate with the institutions of publishing. When she created herself author, editor, and publisher, she situated her production in a field of free transgressive prediscovery.

It is over a hundred years after her death; if I am writing a book and I quote from one of her letters or poems and use either the Johnson or Franklin edition of her texts, I must obtain permission from and pay a fee to

The President and Fellows of Harvard College

and the Trustees of Amherst College."is this the Hope that opens and shuts, like the eye of the Wax Doll?

Your Scholar—" (L 553)

"This is the World that opens and shuts, like the Eye of the Wax Doll—"

(L 554)

* * *

(MBED 2:1047; 55)

Poetry is never a personal possession. The poem was a vision and gesture before it became sign and coded exchange in a political economy of value. At the moment these manuscripts are accepted into the property of our culture their philosopher-author escapes the ritual of framing—symmetrical order and arrangement. Are all these works poems? Are they fragments, meditations, aphorisms, events, letters? After the first nine fascicles, lines break off interrupting meter. Righthand margins perish into edges sometimes tipped by crosses and calligraphic slashes.

(MBED P1413).

Define the bounds of naked expression. Use.

All scandalous breakings out are thoughts at first. Resequenced. Shifted. Excluded. Lost.

"She reverted to pinning slips to sheets to maintain the proper association" (MBED p1413).

Oneness and scattering.

Marginal notes. Irretrievable indirection—

Uncertainty extends to the heart of replication. Meaning is scattered at the limit of concentration. The other of meaning is indecipherable variation.

In his preface to The Poems of Emily Dickinson, called "Creating the Poems," T. H. Johnson referred to her "fear of publication," as many others have done other since. He called her poems "effusions." During the 1860s, "[h]er creative energies were at flood, and she was being overwhelmed by forces which she could not control" (PED xviii).

"Over; more than enough; noting excess; as, a thing is too long, too short, too high, too many, too much" (WD 1159).

(

MBED 2:797; f33)

Wayward Puritan. Charged with enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is antinomian.

(MBED 2:1342: S11 "about 1871")

Key

AC E1 E2 L MBED ML P PED WD |

The Antinomian Controversy: David Hall, ed. Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson (First Series). Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson (Second Series). The Letters of Emily Dickinson: Johnson and Ward, eds. (pf, prose fragment) The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson: R. W. Franklin, ed. (f, fascicle; s, set) The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson: R. W. Franklin, ed. Poems by Emily Dickinson: Todd and Higginson, eds. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Thomas H. Johnson, ed. An American Dictionary of the English Language: Noah Webster. |

Sources

Emily Dickinson. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. 3 vols. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1958.

———. The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols. Edited by R. W. Franklin. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1981.

———. The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson. Edited by R. W. Franklin. Amherst, Mass.: Amherst College Press, 1986.

———. Poems by Emily Dickinson. Edited by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1891.

———. The Poems of Emily Dickinson. 3 vols. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1951.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson. First Series. Boston and New York: Riverside Press, Houghton Mifflin, 1865.

———. Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Second Series. Boston and New York: Riverside Press, Houghton Mifflin, 1876.

Hall, David D., ed. The Antinomian Controversy, 1636-1638: A Documentary History. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1968.

Webster, Noah. An American Dictionary of the English Language. Revised and enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich. Springfield, Mass.: George and Charles Merriam, 1852.

——. Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged. Edited by Philip Babcock Gove, Ph.D., and the Merriam Webster editorial staff. Springfield, Mass.: G. & c. Merriam Company, 1971.

Notes

My title is the seven last words of Emerson's essay called "Circles."

"'A man,' said Oliver Cromwell, 'never rises so high as when he knows not whither he is going.' Dreams and drunkenness, the use of opium and alcohol are the semblance and counterfeit of this oracular genius, and hence their dangerous attraction for men. For the like reason they ask the aid of wild passions, as in gaming and war, to ape in some manner these flames and generosities of the heart" (E1 322.).

I have tried to match the poems in type, as nearly as possible, to the Franklin edition of The Manuscript Books. In translating Dickinson's handwriting into type I have not followed standard typesetting conventions. I have paid attention to space between handwritten words. I have broken the lines exactly as she broke them. I have tried to match the spacing between words in the lists at the end of poems. I have not been able to pay attention to spaces between letters. I think that in the later poetry such spacing is a part of the meaning. Dickinson's frequent use of the dash was noted in the Johnson edition, but he regularized these marks. I know that in some books printed during the nineteenth century, variant readings were sometimes supplied at the end of a page, and they were marked by a sort of cross. The History of New England from 1630 to 1649, by John Winthrop, edited by James Savage, and published in Boston in 1826, is a good example of such practice; however, if there were more than two words, a number was used for the second one, and in other books the number of crosses increased for each word. Emily Dickinson had enough humor to read these variants as found poems. She was her own publisher and could do as she liked with her texts. These were the days of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll; liberties were taken in print.

The bottom of a page of the Savage edition of Winthrop's History looked like this:

some other place, which they both consented to, but still the difficulty remained; for those three, who pretended themselves

||conferred|| ||2step|| ||3we|| ||4taking|| ||5her||

39 VOL. 1.

Reason 2. All punishments ought to be just, and, offences varying so much in their merit by occasion of circumstances, it would be unjust to inflict the same punishment upon the least as upon the greatest.

||theft|| ||2presumptuous||

These manuscript books and sets represent the poet's "letter to the world." The discovery of these packets and sets galvanized her sister Lavinia into action. If Dickinson sent some of the poems in letters to friends, she also left these packets in a certain order. It is doubtful, to say the least, whether her various correspondents would have bothered to collect and then publish her poem-letters.

I have followed Johnson's choices for capitals, although I feel I could argue with his choices at times. I have been allowed access only to the originals of two manuscript books, and as a result I wouldn't dare to. In a review of The Poems of Emily Dickinson, published in the Boston Public Library Quarterly, July 1956, the poet Jack Spicer suggested such marks might have been meant as signs "of stress and tempo stronger than a comma and weaker than a period." The new critical edition must reconsider such questions. In the early fascicles, Dickinson frequently uses exclamation marks. Around fascicles 6-12, as she begins to break her lines in a new way and to regularly insert variant words into the structure of her work, nervous and repetitive exclamation marks change to the more abstract and sweeping dash. Sometimes the way she crosses her t’s (and this no printed version could match) seems to influence the length of the direction of the dash. The crosses she added to her texts when she included variant word possibilities should also be translated into print. The most frequent argument in favor of Johnson's changing the line breaks is the assumption that Dickinson (thrifty Yankee spinster) broke her lines at the righthand margin because of the size of the paper she was using. In other words, she ran out of space and wanted to save paper. Close examination of the Franklin Manuscript Edition shows that she could have put words onto a line had she wished to; in some cases she did crowd words onto a line. As she went on working. Dickinson increased the space between words and eventually the space between letters. If you follow Johnson's edition, you get the idea that there was no change in form from the first poem in fascicle 1 to the last poems in the sets.

In the long run, the best way to read Dickinson is to read the facsimiles, because her calligraphy influences her meaning. However, Franklin's edition is far too expensive for most people, and then there is the added difficulty of reading handwriting. I think her poems need to be transcribed into type, although increasingly I wonder if this is possible. If the cost of The Manuscript Books is prohibitive, what would an edition of the Collected Letters cost? Can the later letters and poems be separated into different categories? I am a poet, not a textual scholar. In 1956, Spicer wrote: "The reason for the difficulty of drawing a line between the poetry and prose of Emily Dickinson is that she did not wish such a line to be drawn. If large portions of her correspondence are considered not as mere letters—and indeed, they seldom communicate information, or have much to do with the person to whom they were written—but as experiments in a heightened prose combined with poetry, a new approach to her letters opens up." He based his opinion on careful examination of the letters and poems owned by the Boston Public Library.

For its time the Johnson edition was a necessary contribution to any Dickinson scholarship. It radically changed the reading of her poetry. I can't imagine my life as a poet without it. But as Emerson wrote in "Circles," "The universe is fluid and volatile. Permanence is but a word of degrees. . . . Our culture is the predominance of an idea which draws after it this train of cities and institutions. Let us rise into another idea; they will disappear." A lot has changed in poetry and in academia since 1951. The crucial advance for Dickinson textual scholarship was Ralph Franklin's facsimile edition of The Manuscript Books. Now the essentialist practice of traditional Dickinson textual scholarship needs to acknowledge the way these texts continually open inside meaning to be rethought. In a Dickinson poem or letter there is always something other.

Cristianne Miller, in Emily Dickinson: A Poet's Grammar (1987, Harvard University Press), discusses Dickinson's use of Noah Webster's introductory essay to his American Dictionary. Paula Bennet, in Emily Dickinson: Woman Poet (1990, Harvester Wheatsheaf, Key Women Writer Series), has kept to Dickinson's lineation and her method of indicating the variants with a cross, as long as she has been able to work from poems in the facsimile edition. Martha Nell Smith discusses the problem of textual meddling with Dickinson's letters to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, in "To Fill a Gap" (San Jose Studies 13, 1987). I am looking forward to Sharon Cameron's forthcoming book, with the wonderful title Choosing Not Choosing, about the manuscript books. Marta Werner is currently at work on a group of late letter-poems. These scholars are showing new directions for Dickinson scholarship.

* Emily Dickinson owned an 1844 reprint of Webster's 1840 edition. The family owned the 1828 two-volume first edition. Webster, a friend of the Dickinson family, was a resident of Amherst, helped to found Amherst College with Samuel Fowler Dickinson and served on the board of the Amherst Academy with Edward Dickinson.