UN COUP DE DÉS

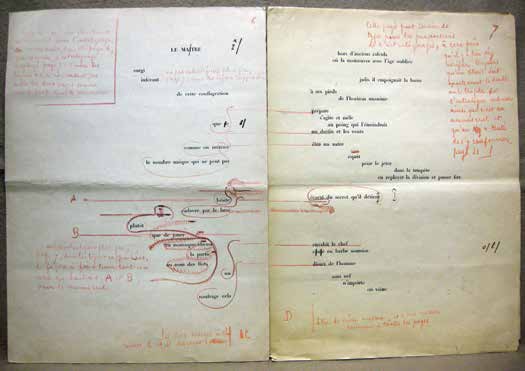

1897 first proof of Un coup

1897 Ms via Monoskop; Monoskop page

HTML white on black {note: set view/character encoding to Western if accent marks do not display properly

2002 full size version (Michel Pierson)

Basil Cleveland translation (via UBU)

Christopher Mulrooney translation (via UBU)

A.S. Kline tr.

Word lists and more from Un Coup de Dés

"Toute revolution est un coup de dés," Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub (1977): assigns the words of the poem to nine different speakers, separating each from the other and using slight pauses to correspond with white spaces.

Marcel Broodthaer's version (1969): installation shot (by Ch. B.)

"Deformative" translation by Chris Edwards, "A Fluke"; French original (HTML spreads)

John Tranter's "Desmond's Coupé"

"Salut"(1893) -- in four versions; English translations

Gerald Bruns,

"Mallarmé: The Transcendence of Language and the Aesthetics of the Book" (1969)

Mallarmé's Preface

of 1897

'I would prefer that this Note was not read, or, skimmed, was

forgotten; it tells the knowledgeable reader little that is beyond

his or her penetration: but may confuse the uninitiated, prior

to their looking at the first words of the Poem, since the ensuing

words, laid out as they are, lead on to the last, with no novelty

except the spacing of the text. The 'blanks' indeed take on importance,

at first glance; the versification demands them, as a surrounding

silence, to the extent that a fragment, lyrical or of a few beats,

occupies, in its midst, a third of the space of paper: I do not

transgress the measure, only disperse it. The paper intervenes

each time as an image, of itself, ends or begins once more, accepting

a succession of others, and, since, as ever, it does nothing,

of regular sonorous lines or verse – rather prismatic subdivisions

of the Idea, the instant they appear, and as long as they last,

in some precise intellectual performance, that is in variable

positions, nearer to or further from the implicit guiding thread,

because of the verisimilitude the text imposes. The literary

value, if I am allowed to say so, of this print-less distance

which mentally separates groups of words or words themselves,

is to periodically accelerate or slow the movement, the scansion,

the sequence even, given one's simultaneous sight of the page:

the latter taken as unity, as elsewhere the Verse is or perfect

line. Imagination flowers and vanishes, swiftly, following the

flow of the writing, round the fragmentary stations of a capitalised

phrase introduced by and extended from the title. Everything

takes place, in sections, by supposition; narrative is avoided.

In addition this use of the bare thought with its retreats, prolongations,

and flights, by reason of its very design, for anyone wishing

to read it aloud, results in a score. The variation in printed

characters between the dominant motif, a secondary one and those

adjacent, marks its importance for oral utterance and the scale,

mid-way, at top or bottom of the page will show how the intonation

rises or falls. (Only certain very bold instructions of

mine, encroachments etc. forming the counterpoint to this prosody,

a work which lacks precedent, have been left in a primitive state:

not because I agree with being timid in my attempts; but because

it is not for me, save by a special pagination or volume of my

own, in a Periodical so courageous, gracious and accommodating

as it shows itself to be to real freedom, to act too contrary

to custom. I will have shown, in the Poem below, more than

a sketch, a 'state' which yet does not entirely break with tradition;

will have furthered its presentation in many ways too, without

offending anyone; sufficing to open a few eyes. This

applies to the 1897 printing specifically: translator's note.)

Today, without presuming anything about what will emerge from

this in future, nothing, or almost a new art, let us readily

accept that the tentative participates, with the unforeseen,

in the pursuit, specific and dear to our time, of free verse

and the prose poem. Their meeting takes place under an influence,

alien I know, that of Music heard in concert; one finds there

several techniques that seem to me to belong to Literature, I

reclaim them. The genre, which is becoming one, like the symphony,

little by little, alongside personal poetry, leaves intact the

older verse; for which I maintain my worship, and to which I

attribute the empire of passion and dreams, though this may be

the preferred means (as follows) of dealing with subjects of

pure and complex imagination or intellect: which there is no

remaining justification for excluding from Poetry – the

unique source.'

page edited by Charles Bernstein (updated March 2016)