|

|

Smooth as a ballet jump and as lightning fast as it appears effortless, the left hand holding the ball dips slightly and the racket slides low and backward until the hands and the racket begin to rise in unison, picking up speed as the ball--held carefully in the fingertips, not the palm, so as not to impart spin when released--is tossed precisely nine-feet, six inches high. The right arm speeds into action, flexing at the elbow, the angular bended-joint pointing up toward the sky but the racket hanging parallel to the spine like a back scratcher, the tip of the frame near the waist for only a speck of a moment before rushing forward and up as the arm straightens out-not unlike the easy motion of a wiry, loose-armed baseball pitcher throwing his fastball. The racket head travels on a rising circular path to catch up with the sphere that hangs still for a split second as the rising ball struggles and ultimately wavers against the overwhelming power of the biggest ball--and by that I mean the earth, this planet that that is constantly spinning, imparting the power of weighted gravity upon us all, the tennis playing and the non-tennis playing alike. The ball hangs there momentarily in limbo, neither dropping nor rising, but levitating, waiting to be hit. The racket obliges, colliding with the ball in its apex, flattening its roundness out there for no more than an incalculable millisecond, sending the ball flying horizontally and slightly, ever so slightly, downward so that it crosses over the three-foot-high net, a distance of thirty-nine feet from the baseline, and lands with great velocity into the back edge of the 283.5 square feet of service box, skidding onto the white line fifty-nine-feet and eleven inches away and flying up with the pace of a dove in a field of millet hearing a shotgun blast. The body follows naturally into the court. The racket returns to the ready position, the feet line up, the eyes look forward. The ball is in play. Another point has begun.

| The Germantown Cricket Club |

Philadelphian William "Big Bill" Tatem Tilden II dominated tennis in the twenties, achieving fame on par with Babe Ruth's. He was born in 1893 at his family's home at 5015 McKean Avenue, one block from where he learned to play tennis at Germantown Cricket Club. When he was fifteen and his mother became ill, he moved in with an aunt and her niece only few blocks away at 519 Hansberry Avenue. He kept a bedroom in the Hansberry house for thirty-three years.

All of Tilden's immediate family died prematurely. Nine years before he was born, the Tildens lost three children to the diphtheria epidemic, and by the time Tilden was nineteen, both parents and an older brother had died of illnesses.

Tilden graduated from Germantown Academy and attended the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to tennis, he acted and wrote newspaper articles, short stories, a novel, and plays. He also produced several Broadway plays, starring in his production of Dracula.

His lifelong fondness for boys ultimately led to his demise in the late forties in Los Angeles, where he was twice convicted for sexual indiscretions with teens. He was penniless near the end of his life, hocking all of trophies, including the Wimbledon cup. He died of a heart attack at the age of sixty in 1953 in his low-rent apartment near Hollywood and Vine, his bags packed for a trip the next day to a professional tournament in Cleveland.

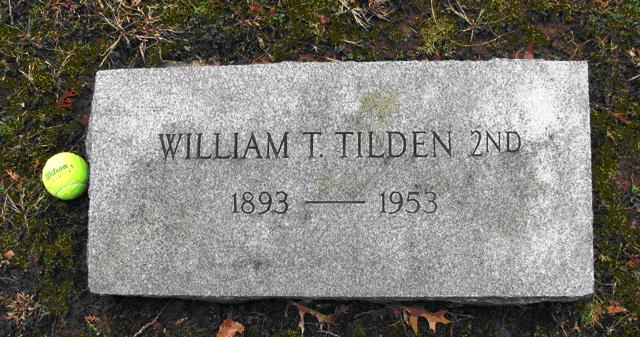

He was cremated because it was cheaper than shipping a coffin back to Philadelphia. His ashes are buried and marked with a simple gravestone at Ivy Hill Cemetery, the only monument in the world in his memory.

ESPN ranked Tilden as the forty-fifth greatest athlete of the 20th Century. His record of six straight U.S. Championships (now the U.S. Open) still stands, although Roger Federer could tie the record later this year.

Joe Samuel Starnes, in addition to his personal blog linked to his name, also maintains a tennis blog that can be found here.

Back to main page.