American Book Review

Volume 33, Number 2, January/February 2012

pp. 12-13

A Poetics of Social Acts

Rosemary Winslow

The University of Chicago Press

I am filled with regret and overcome with the errors of my ways, for I have preferred the crooked path over the straight, the bent over the upright, the hunched over the erect. I recant and cant my recantation. I altogether abandon the fetishizing of the sounds and forms and appearances and rhetoric of a poem. The innermost meaning of poems reveals itself when sound, form, appearance, rhetoric, and oratory fall away.

—Charles Bernstein

Time... / Worships language and forgives / Everyone by whom it lives.

—W. H. Auden

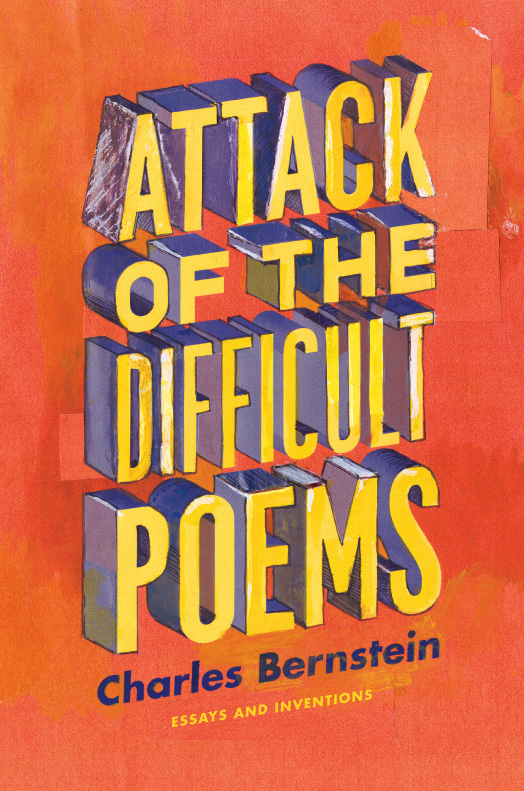

By his own account, Charles Bernstein has fought the good fight for language-centered poetry and criticism against "Official Verse Culture," although it is questionable at this point in time, when Rae Armantrout has won a Pulitzer, whether Language Poetry remains outside acceptable poetry culture. In this collection of his published essays, talks, and book reviews, a thirty-year-long apologia is sent forth to present arguments to writers, readers, academics, and critics on his views on aesthetics and aestheticism. The book is launched by a short introductory parody of the self-help genre and concluded with a parody, rich in wit and feeling, styled in the manner of famous recants as Chaucer's and Galileo's. The individual pieces are of-a-piece with the parodic title subject, Attack of the Difficult Poems. Recalling parody of the war-driven, 1940s and 1950s B-film genre, the views are lucidly presented, closely argued, lucid, and for the most part sensible—oddly, the opposite of what Bernstein values in poems.

By his own account, Charles Bernstein has fought the good fight for language-centered poetry and criticism against "Official Verse Culture," although it is questionable at this point in time, when Rae Armantrout has won a Pulitzer, whether Language Poetry remains outside acceptable poetry culture. In this collection of his published essays, talks, and book reviews, a thirty-year-long apologia is sent forth to present arguments to writers, readers, academics, and critics on his views on aesthetics and aestheticism. The book is launched by a short introductory parody of the self-help genre and concluded with a parody, rich in wit and feeling, styled in the manner of famous recants as Chaucer's and Galileo's. The individual pieces are of-a-piece with the parodic title subject, Attack of the Difficult Poems. Recalling parody of the war-driven, 1940s and 1950s B-film genre, the views are lucidly presented, closely argued, lucid, and for the most part sensible—oddly, the opposite of what Bernstein values in poems.

Not a fan of his poetry, I was thoroughly engaged by his discussions and found myself in agreement with a good deal of what he had to say. Bernstein's aesthetic values center on an aestheticism of direct contact, sound, and "linguistic sensation" established in social contexts—shifting, fluid, changeable with the times and different readers. Poems are not to be left to themselves. Poems are to be experienced in the body. The concept of an ideal individual self presented and assumed as a voice in a poem is anathema to the value of poems' uses. Contrast and conflict do not have to resolve in interpretable meanings. The search for definitive meaning is counter to the nature of poems. Readers, as in any responsible relationship, are in charge of reading poems, poems are not in charge of readers: "Don't let the difficult poem intimidate you! Often the difficult poem will provoke you, but this may be its way of getting your attention. Sometimes, if you give your full attention to the poem, the provocative behavior will stop." And: "Learning to cope with a difficult reading of a poem will often be more fulfilling than sweeping difficulties under the carpet, only to have the accumulated dust plume up in your face when you finally get around to cleaning the floor." Thus, a sampling of wit that is one of the great pleasures of criticism, almost lost in the reign of academia over poetry, that Bernstein, himself an academic for the past two decades, returns to us.

Leading off the first of three major sections is a lengthy essay on teaching: "A Blow Is Like an Instrument: The Poetic Imaginary and Curricular Practices" argues for poetry as practice and performance in place of the traditional ("Professional") critique. Instead of explicating poems, as artifacts, poems return to their status as art: students read, listen, respond, and write about how the poem proceeds from beginning to end as a performance of language. Content and meaning are not essential outside of language used with craft. This was my favorite chapter, as I already agreed with this position, and teach students to attend to the sound and feel of flowing language. For some poets, such as Emily Dickinson, this is the only approach that unleashes the power and greatness of her art. If something can be said, there is no reason to write poetry. The aesthetic aspects are what make it art, and that purpose must be included with the more traditional treatments of history and meanings. The teacher's job is to put the tools of reading poems into the hands of students, whereas the vast majority of instruction in poetry mystifies and intimidates by insisting on professionally determined senses of poems. Bernstein would take poems out of books and put them in real contexts, which are always and already alive with people, genres, interactions, frames, institutions, and so on. How they get used in various times and places for various reasons is the life they begin upon publication. Poems are not dead, not monuments; on the contrary, they live. They may be timeless, because they keep being read and keep speaking to actual people and they continue to be listened to. Several brief essays follow this long essay, revisioning what poetics and its teaching could/should be: a justification for innovative poetries that diverge from "the rote evocation of Emerson" that includes a proposal for an "aesthetics of NO" that resists the poetry of light and uplift; a welcome return to the traditional reasoned grounding of critical judgment is a stated theory of what a poem is (Bernstein's sound and the visceral—embodied language); a curriculum and activities for teaching a poetry course (great ideas to take straight to the classroom); a review of Al Filreis's 2007 book, Counter-Revolution of the Word: The Conservative Attack on Modern Poetry 1945-1960, which examined the alignment of anti-modernist poetics with anti-communist politics in the postwar years contributed to the long history of American anti-intellectualism that mounts periodic attacks on difficult poems; and perspectives on what a poetics of the Americas might look like.

The middle section of the book takes up "The Art of Immemorability"—Bernstein's term for an aesthetics of language performance (oral and/or written/digital) positioned counter to the popular poetry of "uplift" and poems as monuments to culture. The long essay "Objectivist Blues: Scoring Speech in Second Wave Modernist Poetry and Lyrics" is the centerpiece of the book—a brilliant tapestry of the interwoven arts using sound and resounding in the period after high modernism. First published in the prestigious scholarly journal American Literary History, the essay traces out threads of ethnic and gendered high and low culture, mass and popular consciousness, music and poetry, and visual arts. We discover Fanny Brice and Claude McKay woven into Oscar Hammerstein, Dada and Russian folk song mix with blues and scat, Cole Porter and Johnny Mercer pick up hoodoo and commercial culture, Paul Robeson montages "a utopian space in which solidarity and struggle move us closer to imagining a just world." Bernstein's poetics are counter-mainstream and counter-academia, and he convinces that we need a wider and deeper scope that takes in the social, political, and cultural mix the arts themselves gather to compose.

The third section of essays, "The Fate of the Aesthetic," gathers work that delves into the issues presented in the first half of the book: problems of ethnicity, visual arts, translation, the sacred and the secular, the sublime and the ordinary. The lead essay, a review of three books by Jerome McGann, supports and clarifies Bernstein's own position, expressed in foregoing and following essays. Bernstein discusses McGann's view on the poem as a social act always immersed in human life: "a poem is a social event—a work of literature—embedded in a dynamic, multilayered historical and ideological context." By contrast, the text is, like a musical score, a flat linguistic set of signs and directions, a "document" but not itself a work of art.

This leads me to ponder what this book has to offer fans of the essay genre. Bernstein's voice is strong, serious, and playful, despite his disavowal of the reality of voice, and his essays flesh out conventional forms or often playfully refuse to play by the rules of form ("Fraud's Phantoms," "Fulcrum Interview," "Poetry Bailout," "Recantorium"). Though these essays and the ideas presented are not new, the mainstream of the essay genre is a match for the poetry world mainstream. Let me seed some of Bernstein's notions from poem to essay: an essay is a social act and event. An essay is always embedded in a social context. There is no idealized self as voice expressing through language; rather, the writing emerges from a social role and meets the reader in a social role. The stream of sound is the essay, not the words on the page. The work of art is the language brought to life by the reader; it is not the artifact composed into a flat dead text. The essay is the living performance co-created by the text and the reader. I think here of Thelonious Monk's directive for listening that I like to tell my students regarding both learning anything and reading poems: "I lay it down, but you got to pick it up."

Rosemary Winslow is a poet and professor of literature and rhetoric at Catholic University of America. In addition to Green Bodies, a collection of poetry, she has published poetry in The Southern Review, Innisfree, and elsewhere, as well as numerous essays on poetics, prosody, metrics, and related concepts.