NYQ: What poets have influenced your work?

PAUL BLACKBURN: W. H. Auden was an early influence. My mother sent me a copy of his Collected Poems when I was in the Army. When I was nineteen, I could write a pretty good Auden poem, and I feel that I picked up a formal sense of musical structure from him. In college I began to read Ezra Pound. His Personae, not to mention the Cantos, was an incredible revelation to me as to what you could do in terms of making music with different line lengths, and how, rhythm could be so rich and varied. I think I learned a lot of my ear from reading Pound. At the same time I was studying Pound, I was picking up influences from my contemporaries—Robert Creeley, Charles Olson and Cid Corman. I was learning to strip my style of as much as I could and get down to very simple statements while still keeping it reasonably musical. I think a lot of the William Carlos Williams influence came to me, not through Williams so much, as through Williams' influence on Creeley. In a review of my first book, the critic blamed both Creeley and me on Williams. I thought, "Oh, wow! I've got to read Williams!" So I got ahold of Paterson, and what was then his Collected Poems. I wanted to find out where my influences were coming from. I wanted to find out who my father was.

NYQ: Those contemporaries you mentioned—Creeley, Olson, Corman—-didn't you all form the Black Mountain School of poetry?

PB: Black Mountain doesn't do at all as a label; because presumably it should apply to the people who either studied or taught at Black Mountain College, and it doesn't. Robert Duncan taught at the college and contributed to The Black Mountain Review, but he really can't be considered to be Black Mountain. He's much more musical than many of the Black Mountain people. And he doesn't necessarily work from speech rhythms—he's more formal. Mostly what this Black Mountain thing is all about is what we were all working at—speech rhythm, composition by field, or something from that set of ideas. By 1951, Olson had tied a lot of it together in that "Projective Verse" essay. So we even had a set of principles to keep in our heads. But this is not to say that we were developing similar styles. Does Creeley write like Olson, does Olson write like Denise Levertov? In the end, every poet is an individual, and if you can group them it's because they drink together once in a while.

NYQ: You said that you "learned a lot of your ear from reading Pound." Your ear must play a great part in the writing of your poetry.

PB: Certainly the ear is a prime judge of what I've accomplished or have not accomplished. I wouldn't even know whether a poem was finished or not unless my ear told me. I think music must be in the poem somewhere. Poetry is traditionally a musical structure. Now that forms are as open as they are, each poem has to find its own form. It has to do with the technique of juxtaposition and reading from the breath line and normal speech raised to its highest point. But that's abstracting a principle. When you're writing, these things are at the back of it. It's almost as though your technique is in your wrists and you're sitting at a typewriter instead of at a piano. As far as I'm concerned, people who don't hear the poems are missing a good deal, and a poet who doesn't hear his own poems is missing everything. He's got to hear his own voice saying it. It's got to come off the page in a way that concrete poetry cannot.

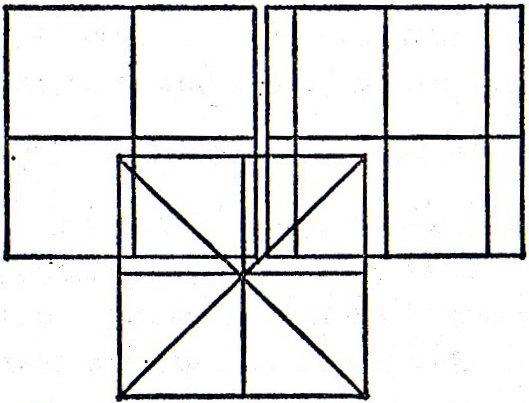

NYQ: What do you feel about concrete poetry?

PB: Concrete poems are not written to be read aloud, they're written as objects. In other words, they have to stay on the page. It has to do with the arrangement of sounds and words, of their interpolations or their, extrapolations, how, they mix or cross. I mean, it's there on the page, whatever the joke is. And basically it is a game. It can be a particularly beautiful game or a fairly dull one, depending on who's playing it.

NYQ: Do you play that kind of game?

PB: No, I've never been able to stand crossword puzzles, anagrams, that kind of thing.

NYQ: What purpose do punctuation and indentation serve in your poetry?

PB: Punctuation serves much the way that spacing does—that is, to indicate the length of a pause. For example, if there is a space between the last letter of a word and the period, the pause is longer than it would be if the period were right beside the last letter. If there is a period, the pause is longer than it would be if there were no punctuation and you moved over to the left margin to pick up the next line. There is a longer pause between the end of the line and the left margin than there is between the end of the line and the succeeding line picking up in the middle or three-quarters of the way through the line. And certainly even less of a pause (because this is the way the eye runs) if it moves to the end of the line and simply drops off and continues on the next line: So you're using the common way of reading to control the speed of the words as read.

NYQ: What importance does form have in your work?

PB: Strict form is by no means a necessity. Quite the opposite, each poem must find its own music, its own form. It's much harder to do that than to write quatrains all the time.

NYQ: How do you respond to criticism?

PB: It depends on who's doing the criticizing. If it's someone like Cid Corman, I'll listen, I'll consider it seriously, even if I think he's dead wrong. But there aren't many editors or critics who are in his category. He's a solid man. You wouldn't dare send him anything but your best work.

NYQ: Have you published any criticism?

PB: I've written two articles for Kulchur. One was an analysis of the whole Black Mountain thing, the other was about Robert Kelly. I consider Kelly to be a great poet. As a matter of fact, I considered him to be a great poet before he was thirty, and there aren't many people who are willing to make that kind of statement about a man who is under thirty. But I'm an amateur, I'm no professional critic. Anyway, I hate writing prose—I've never taken any pleasure in writing it.

NYQ: Do you feel that poetry workshops are useful?

PB: It depends on the student and what he's ready for. Certainly, to be in a group of people working together is often a very valuable experience for a young person. Not only what he may get in the way of advice from his instructor, but also the reactions of his contemporaries. However, it can be completely useless if a writer not only feels cut off, but wants to feel cut off, and insists on cutting himself off. He'll have a miserable time in the workshop because part of the learning process does depend not only upon his easy relationship to his instructor (and presumably the instructor has something to say that will be of use), but also upon his not building his defenses so great that he can't move past where he is. If he's already got his` head set and he doesn't want to break it-if he wants to stand there and prove how good he is to everybody then he's liable to get nowhere in the workshop. With such people it's sometimes useful just to blow their minds, to open them up and see what happens. So that's one value of a workshop—the opening up. Another value is giving the person a built-in audience. A young writer doesn't get a set of intelligent mirrors very often. Friends are something else. They may be helpful if they are themselves writers. Otherwise, they're liable to act as a dear reassurance which, God knows, is a necessity sometimes. But a workshop situation gives, at best, a fair cross section of a potential audience, lets you know if you're coming across—and how, and why.

NYQ: Where do you write?

PB: Anywhere, anytime, when it hits me I write. I don't ask any questions. It can be dead silence, the kid (his six-month-old son, Carlos) can be screaming, I can be sitting on the subway during rush hour. You write when you have to write, when it comes to you. Some people need a formal circumstance around them in order to write. I don't. Neither do I schedule myself when I'm writing poetry. However, I do schedule my translating. Translation requires a steadier concentration. But getting back to the question, what happens when you're being dictated to and you don't know where the dictation is coming from? All you know is you have to sit down and write it and you may not know what the damn thing means when you're done. And somehow, later'on, you find out where the piece belongs—either in a long poem or as a separate piece.

NYQ: Tell us something about your translations.

PB: I don't become the author when I'm translating his prose or poetry, but I'm certainly getting my talents into his hang-ups. Another person's preoccupations are occupying me. They literally own me for that time. You see, it's not just a matter of reading the language and understanding it and putting it into English. It's understanding something that makes the man do it, where he's going. And it's not an entirely objective process. It must be partially subjective, there has to be some kind of projection. How do you know which word to choose when a word may have four or five possible meanings in English? It's not just understanding the text. In a way you live it each time, I mean, you're there. Otherwise, you're not holding the poem.

NYQ: How do you feel about writing in a travel situation?

PB: I think travel is an ideal situation in which to write. In a way there's a kind of spiritual and sensory vacuum present. Take the subway, for instance. People blank out, you see the dullest faces there. What are they thinking, what are they doing? They're going from here to there and nothing's happening to them. They'd be lucky to have their pockets picked, at least that would be something. So you see, the demands on you as to movement or thought or even personal contact are minimal. And I have an idea that a lot of things come to the surface in such a situation that might not otherwise get there. The only thing left to come into this vacuum is whatever is in your head at that particular moment. And although the subway is moving, you're stationary; you're always looking at the same thing. Then there's the sound, trolleycars, trains, wheels on the tracks, will set rhythms going in your head, a kind of ground rhythm against which your own ear works, can turn you on, turn your voice into that emptiness. Buses also, especially on wet pavement. I always feel very sensual on buses, never so on planes, there's too much formality, all those chicks serving you drinks and food. I'd rather read or sleep or stare out the window at cloud formations. One is really stationary in a plane, you're being boxed or shipped, and the sound is a constant roar—no rhythm to it, and muted besides. Ginsberg wrote his Wichita Vortex Sutra on a plane, though, so we can't eliminate the possibility of that working for some people. Allen has a panvision of the world anyway. John Keys has a couple of poems from an aircraft point of view. ". . . the clouds like a parking lot/sort of hump hump hump, if you see what I mean." It would be different on a boat because you could get up and walk around, vomit on the deck or something. At least there's a kind of personal movement on a boat which cannot be found on most other types of conveyances. It's not the boat that makes the waves, but where we are right now, as they say, the motion of the ocean. To come back to the city, though, the subway is an incredible place for girl watching. You find one face or a good pair of legs—you can look at them for hours. You think, "Oh god, I hope she doesn't get off at 34th Street."

NYQ: What do you do when you have a dry period, when you can't write?

PB: I don't get upset about it. As a matter of fact, I'm happy when I'm not writing. When I'm writing, I've got to work. Not that writing isn't a joy—it is at times, but there are great periods when I simply don't write anything or very little. In a very real way I use translations to fill in that time, because I do enjoy translating, getting into other people's heads.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Cities, New York, Grove Press, Inc., 1967.