On

Robert Grenier’s ‘Drawing Poems’:

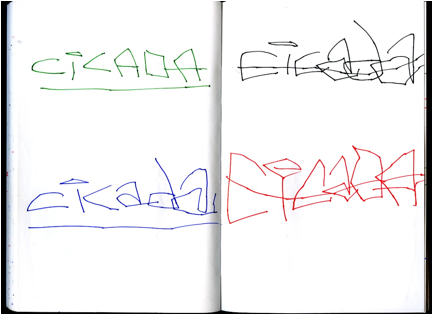

“CICADA

/ CICADA / CICADA / CICADA”

(Thinking

[Writing/Making] Things)

The word

“idea” comes from the Greek eidow which

means to see, face, meet, be face-to-face.

We stand

outside of science. Instead we

stand before a tree in bloom for example – and the tree stands before

us. The tree faces us. The tree and we meet one another, as the

tree stands there and we stand face to face with it. As we are in this relation of one to the

other and before the other, the tree and we are. This face-to-face meeting is not, then,

one of these “ideas” buzzing about our heads. . . . We come and stand – just as we

are, and not merely with our head or our consciousness – facing the tree

in bloom, and the tree faces, meets us as the tree it is. Or did the tree anticipate us and come

before us. Did the tree come first

to stand and face us so that we might come forward face-to-face with it?

Martin

Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking

On April 23 , 2011 (which happens to have been Shakespeare’s

birthday,

a fact noted several times in what followed) Robert

Grenier and I sat

down in my living room in Bolinas to record what became

the fourth of

four conversations (“On Natural Language”), all four of

which together

with “images of each of

the drawing poems under consideration” can be

found at PennSound. What follows here is a reconsideration of

the first of

the drawing poems (“CICADA / CICADA / CICADA / CICADA”)

that we talked

about that rainy afternoon, beginning with some further

thinking about

what it was that we were talking about. Here is a scanned copy of the

poem (as it appears on PennSound):

The poem is a visual shape in letters of the “sound

pattern” that RG

had heard several years before, one summer in Long Island,

which had

been ‘conserved’ (in his memory), then brought forward

(mysteriously,

‘once again’) to his attention as ‘event’ (not “emotion”

only but the

whole circumstance being “recollected in tranquility”);

which reminds

me of stepping off the ferry boat onto another island

(Corfu) in 1972,

hearing the sound of cicadas going on (and on and on) in

the hot dry

air of a summer afternoon. The letters-made-into-words of RG’s poem

‘visualize’ the sound of those bugs – i.e.,

‘transcribe’ it, ‘enact’

it, ‘perform’ it, bring it into the present moment of

seeing-reading-

hearing the poem itself (as it exists) on the page and/or,

when read

aloud, in the air.

The poem as an articulation of a ‘comprehensive’ sound

event perceived

in Long Island is completely different from that

sound event – indeed,

how could drawn letters possibly be ‘the same’ as (or

anything ‘like’)

‘real’/’actual’ bugs in that physical landscape? –

but it also becomes

it (on the page, in the air), the sound of those

heard but unseen bugs

in that summer scene ‘translated’ here into hand-drawn

letters in four

colors of ink (green, blue, black, red), seen but not

heard unless the

poem is read aloud, at which point the sound of cicadas in

Long Island

(‘vraiment’) ‘becomes’ these letters – “CICADA CICADA CICADA CICADA” –

which transform the language of bugs into our human

language, each one

of these languages conveying ‘meaning’ to those for whom

it is made –

bugs hearing in the sounds they make, one presumes, some

‘message’; we

also seeing and/or hearing something of note in the

poem/name – but is

it a ‘message’? And if so, what does it ‘say’ (or ‘mean’ or ‘import’)?

(It seems, at least at first, that nothing is ‘said’ by

this repeating

of the name of a bug four times; not only is this

[whatever it is] not

a ‘poem’ in any ordinary understanding of that word (no

speaker and no

event being interpreted/presented with significance), it

is not even a

propositional ‘statement of fact’ – nothing is

asserted, grammatically

speaking, since there is no sentence.)

Could it be that the thinking here of that sound event on

Long Island,

the idea of it ‘realized’ in these hand-drawn letters on

the page, has

pushed it out into space (onto the two-dimensional space

of this page)?

Could it be that one can write things themselves –

this ‘thing’ (sound

of cicadas) written into existence, coming into being in

these letters?

Could this be one possible instance of the kind of thing

Heidegger was

‘testifying to’ (possibly also having had some experience

of something

‘like it’) when he said that “The tree and we meet one

another, as the

tree stands there and we stand face to face with it,” that

tree (those

cicadas) made here to exist/‘persevere’ in language? Could it be that

an image (on the page) maintains itself (as image)

in relation to some

previously heard sound pattern, which was itself equally

‘experienced’?

Could it be that a word in English (“cicada”) identical to

the word in

Latin for “A homopterous insect with large transparent

wings living on

trees or shrubs; the male . . . noted for its power of

making a shrill

chirping sound, much appreciated by the ancient Greeks and

Romans” (as

the OED tells us) might be, in naming it,

the ‘same’ as thing it names?

What might it be/mean to write the thing

itself? And what might it be

(or mean) to read it (on page or screen, for instance) or

hear it read

aloud? Could

these drawn letters (arranged as materials, on the field

of a page) create those bugs, make their sounds

(for a reader) ‘become’

present, actually audible?

The image on the page (made of letters) seems

abstract, whereas sounds

of cicadas on Long Island or Corfu (made by the vibration

of membranes

on the underside of their abdomens) are physical, and can

be perceived

by the ear as such: those (male) bugs on those trees and shrubs (over

there in the landscape) calling their mates perhaps . . .

or asserting

their existence, or claiming a place in the territory, or

joining in a

sounding/music all are making (at least four of them) for

the ‘joy’ of

participating, hearing each other’s

cicada-communal-existence-together?

(We don’t really know what they’re doing, can only guess

what it is to

them participating in such communal sounding.) But the four words are

also physically in space: letters drawn by hand in four colors of

ink

which ‘position’ four of those bugs in the space of two

pages, or on a

computer screen; each one spelled “CICADA” but written

differently (in

in different-colored ink but also with different-looking

letters, this

green “C” in the top left not ‘made the same’ as that

black one across

from it, or that blue one below it, or the larger red one

that appears

diagonally across from it in the bottom right); the ground

of the page

(completely white) analogous to (i.e., ‘like’) that

landscape (unseen,

at least here, the offstage action of the landscape in

which bugs were

once sounding the air) made here into a whiteness of

background behind

the words of a poem that (here/themselves) are

‘performing’ that sound.

Which is also to say that these drawn letters of the poem,

even though

they were occasioned by memory of hearing cicadas on Long

Island, here

create a present situation (made of letters), which

is happening ‘now’

(in the writing itself) and remains a possible future

present occasion

for the (unknown) reader who may ‘activate’ it –

i.e., this writing is

not only the conserving of a past event.

What would this poem be if it weren’t drawn by hand? Could it be made

by pressing keys on a computer or typewriter (perhaps an

IBM Selectric,

such as RG used to type the poems in Sentences)? How would it look in

black ink only, typed rather than ‘scrawled’? What would be ‘lost’ in

that translation (e.g., in the “rough translation” that

appears beside

it on the PennSound page), if anything? (A beginning ‘answer’ to this

last question might include, but not be limited to, the

following four

structural features of the

drawing poem [which one might experience in

‘real’ present time; might be of

interest in themselves as ‘forms’ and

in relation to the drawing

poem’s ‘performance’ of cicadas]: note for

instance the triangular green,

triangular blue, rectangular black, and

“e”-shaped red ‘dot’ above each of the four, also

differently ‘shaped’

lower case “i”’s in “CICADA”; the green and blue somewhat

‘horizontal’

lines below the green and blue letters in “CICADA” on the

verso echoed

in the somewhat less horizontal, asymmetrically curved

lines that seem

to scratch across the surface of the black and red letters

[“CICADA”],

perhaps ‘like that branch’ of the tree or shrub on which

each of those

two bugs now appears to sit; a diagonal

symmetry/asymmetry of an upper

case “ADA” in the top left green “CICADA” in relation to

an upper-plus-

lower case “aDa” in the bottom right red “CICADA,” which

is matched by

an apparent symmetry of lower case “ada”s in the blue and

red “CICADA”

positioned on the bottom left and top right of the two

facing pages [I

say “apparent symmetry” because the closer I look at these

letters the

more unlike they seem to be: the ascending line of the blue “d” which

slants up to the left from the almost squared-off corners

of the lower

‘normally curved’ part of the “d” being almost straight,

the ascending

line of the black “d” curving up to the left from an also

curved shape

of the lower part of that letter; each black “a” seemingly

larger than

each corresponding blue “a”]; a strange almost-progression

in the four

words [from top left to bottom right] in which the letters

seem to get

increasingly more jagged, gnarled, or twisted – the

“C”s, all eight of

them [grouped into four sets of a palindrome, “C-I-C,”

matched by four

other sets of a second palindrome, equally unnoticed in

the same word,

“A-D-A”] changing from clean green curve followed by a

45-degree angle

in the top left [green] “CICADA”; to a less cleanly curving

and angled

pair of “C”s in the bottom left [blue] “CICADA”; to the

pair of three-

sided ‘rectangular’ “C”s in the top right [black]

“CICADA”; to a final

much larger pair of trapezoidal “C”s in the bottom right

[red] “CICADA”

which appears [because of its increased size and greater

‘angularity’?]

almost ready to explode off the page, as if the sound of

this “CICADA”

had grown beyond all measure or restraint, even to the

‘breaking point’

[but of what? what will happen on the far side of that

point? will one

enter the cicadas’ world? be transformed into a bug?],

letters-drawing-

bugs getting stranger and stranger, sound appearing to get

louder/more

intense – perhaps because the last, bottom-right

word-bug is literally

bigger but also because, wherever one starts to read, an

experience of

reading builds up a memory of more than the one “CICADA”

one is seeing,

plus also the fact that one can see all four words

at once ‘translates’

into a louder continuum of the sound of all four bugs

together.)

The name itself, “CICADA” – whose second syllable

appears in “cadence”

(which is not etymologically connected to the name for

this bug), that

rhythmic, flowing/falling sequence of sounds unfolding in

time – words,

music, or nature itself: “That strain again. It had a dying fall” as

Orsino says at the beginning of Twelfth Night,

wanting to hear again a

music that “came o’er my ears like the sweet sound/ That

breathes upon

a bank of violets” – a physical thing made of

letters which become the

analogue of not only the bug but the sound it makes (the

sound we hear

when we hear the letters “CICADA” read aloud; the sound we

can imagine

when we see those same letters on the page), takes on

something of the

mysterious power of a fetish: ‘equal’ to the thing itself, it appears

to become it – the bull in the cave painting

at Lascaux and the cicada

in the poem going hand in hand in demonstrating the

condition of ‘real’

bull and cicadas, painter and poet noticing then noting

what otherwise

would disappear, each of them seeking to preserve one’s

fleeting human

experience (perhaps), each of their respective works a

‘form of belief’

testifying to the ‘fetish power’ of an arrangement of

certain lines or,

in this case, letters to ‘stand in’/’stand for’/’be’

something utterly

different – otherwise, only hand-drawn lines made of

‘paint’ (charcoal

or four colors of ink). And, what is more, as hand-drawn lines

(paint

on cave wall, arrangement of letters on page) each of them

making some

actual thing happen ‘now’ . . . this being what a

fetish is ‘for’ – to

accomplish something (by ‘magic’) in the present;

potentially, in this

case, to make (’new’) bugs exist (and sound) and in the

cave paintings

to summon ‘actual beasts’ into the cave, possibly to be

worshipped (in

themselves) or to bring about success in the hunt.

Read aloud, the fact that there are two different ways of

pronouncing

the first “A” of “CICADA” (long and short, i.e., “a” and

“ä”) sets in

motion a variety of alternating rhythms/rhythmic interactions

zinging

between the sounds of any two bugs on the two pages, all

the possible

interactions constructing a ‘force field’ of sound almost

‘equivalent’

(perhaps) to the one made by cicadas in Long Island (a

“faire fielde

full of folke,” as Langland said in Piers the Plowman,

referring not

to bugs but rather “alle maner of men”). It might also be useful to

note that any of the several possible

articulations/sounding-outs of

the series of four “CICADA”s will resemble an amphibrachic

tetrameter

line (compare Browning’s “And into the midnight we

galloped abreast”),

not that this poem is attempting to echo such a “classical

meter” of

course, but rather to ‘realize’ in these letters the

sounds made by,

and positions occupied by, cicadas (which themselves also

exist in a

‘measure’).

Notice also that, despite its apparent ‘minimalism’ (i.e.,

repeating

the word “CICADA” four times), the poem invites a larger ‘metaphoric’

reading, one made possible by the persistent use of the

name “CICADA”

(going back to the Latin word for such bugs, and to what

other names

for such bugs before that?) in ‘historical time’; a

reading that may

lead someone to experience the strangeness of

cicada-giving-birth-to-

“CICADA,” ancient existence of life forms on earth

(and of the earth,

and the cosmos itself) thereby also being ‘summoned’ by a

repetition

of “CICADA.” I

am thinking of how the poem points to a time that is

prior to the time in which one reads it (time

often being ‘a subject’

in RG’s work – think of the poem in Sentences,

which we talked about

in one of the earlier conversations on PennSound, “time to

go to the

laundry again soon”) and of how in reading and thinking

about it one

may well experience a series of metonymic

relations. That is to say,

any way of reading through these four words produces

an amphibrachic

tetrameter line (x/x x/x x/x x/x) in the present time of anyone’s

engagement with the poem, which can be understood to

‘stand for’ the

ninety-plus generations (2,500-plus years?) of human use

of the word

“cicada” that still persists today (the classical measure

going back

to the Greek root suggests this reading) so that

one can imagine one

hears literally millions of bugs, and millions of human

soundings of

the word “cicada,” reverberating through all of those

years on earth.

Beyond that, the time humans have used the word “cicada”

(2,500-plus

years?) can be understood to ‘stand for’ all the years on

earth when

humans/proto-humans had other words for cicadas

(and all such sounds

made by cicadas happening over that time). And beyond that, one can

think of ‘historic time’ (the time when humans had words

for cicadas)

as a metonym for millions of years (how ‘old’ is this bug anyway, in

its present ‘shape,’ capable of making such sounds?),

“cicadas” (but

we can’t even call them that, since there weren’t any

humans to name

them then) going on in their utterly mysterious

sounding/interaction

with each other – beyond our knowing, or any

possible ‘knowledge’ of

such extraordinary beings. And beyond all of that, the existence of

cicadas as a (possible) metonym for all of life (and time)

on earth.

But there isn’t just one bug in RG’s poem but four,

arranged in and as

a grid of words-made-of-letters, composed in the four quadrants

of two

facing pages of a black notebook – four words like

the four lines of a

quatrain:

CICADA

CICADA

CICADA

CICADA

each of whose lines both is and is not the same. (How strange to make

a poem out of one word ‘repeated’ four times – talk

about minimalism!)

The poem takes place on the field of the page in which

letters are put,

bugs and letters arranged in that landscape, the page an

analog in two

dimensions to the three-dimensional world in which the

bugs exist. To

place words on the field of the page – page as place

to work, field in

which the action of the poem takes place, the poem a

“field of action”

as Olson put it, ‘marks-in-space’ as Eigner’s

“calligraphy/typewriters”

suggests:

– is to attempt to build a verbal ‘equivalent’ to bugs

in space. Four

bugs are there on the page, vying with each others’

colors; and in the

air, when the poem is read aloud (making sounds). They are also there

(RG testifies, in the April 23, 2011 conversation) on

these two facing

pages as an ‘offering’ to the actual bugs on Long Island

(which are no

longer there, exist only here on this page – which

came about at least

in part because of RG’s idea of them, his memory of

them made physical

here, as letters-made-into-words). (The white space behind the images

is like offstage action, the landscape in which the action

of the bugs

[making their sounds] originally took place – and

once was heard.) You

can read these four words-made-of-letters any way you want

– across or

down or diagonally you will get to all four eventually,

seen and heard

as living presences on pages that reenact where cicadas were,

in space

– and also where they still are now, for a

reader who ‘activates’ them.

(Isn’t this what Heidegger was asking about in What is

Called Thinking

– how to position oneself to discover the

possibility that words might

‘say’ what is going on? – and out of such, to

construct a ‘true name’?)

Their symmetry there (in the space of the page) is

‘equivalent to’ the

unseen, bygone asymmetry of a location in nature

(on Long Island); and

as such, in the presence of such potentially sonic

materials, we still

may hear what Morton Feldman once called (speaking of the

structure of

one of Webern’s tone-rows) their “intervallic logic,” a

logic of sound

made by bugs in nature ‘played’ as words-made-of-letters

drawn by hand

here (a music that in former times one might have called

“the music of

the spheres,” but here might be more simply called “just

cicada sound,”

– sound made possible in the attempt to write [i.e.,

testify to, as in

ancient practice] ‘it’).

Many thanks to Robert Grenier for his ongoing

‘conversation.’

|