This link takes you back to the main

John Tranter page "Three Poems & an Interview"

Copyright © John Kinsella, copyright © John Tranter, 1995, 1997.

Please see the acknowledgments at the end of the file.

This interview is 11,000 words or about 30 printed pages long.John Kinsella interviews

JOHN TRANTER

John Kinsella: Could you talk about your early years.

John Tranter: I was born in 1943 in Cooma, a little town in the south-eastern mountains of Australia. My father taught in a one-teacher school in the nearby village of Bredbo. It's high country around there, long rolling grassy hills, and pretty much unpopulated. I remember my mother saying that a hot wind blew all summer long, full of dust; in the winter a bitter cold wind, and sometimes snow. We moved to the coastal town of Moruya when I was about four; the climate there was more Californian.

I fell out of the car on the drive to Moruya, late at night. It's almost my earliest memory. On a bend in the dirt road the passenger-side door came open by accident - the car was an old Chevrolet sedan. I'd been asleep in my mother's arms. I fell onto the road and bounced through the blackberries into a ditch. I can still remember staggering to my feet, covered with blood from the gash in my head, and seeing the tail-light disappearing around a bend. It took them a moment or two to realise what had happened, and stop the car. For those few endless seconds it felt very lonely there in the dark.

John Tranter and his father, Bredbo, Australia, circa 1947. Photo Peter Hellier.

My father bought a farm, and I grew up there, learning to drive tractors, to plough and sow crops. Later he started a carbonated drink factory making soda pop, and I drove one of the delivery trucks. He'd been affected by the poverty he saw in the Depression, and he virtually worked himself to death; he died when I was nineteen. He was a decent man, and people liked him.

John Tranter as a boy.

John Kinsella: Could you talk about your early years.

John Tranter: By the time he died in 1962 I'd moved to Sydney and started an intermittent career as a university dropout. I managed nearly a year of Architecture at Sydney University in 1961, and the next year passed some Arts subjects, though I failed first-year English. Then in 1966 I saved some money and went to England on a passenger ship, the Fairstar, and worked at menial jobs in London for a year. Then I hitch-hiked back to Australia across Europe and Asia - Turkey, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India - with my girl-friend Lyn, exploring the hippy trail and having various adventures. I was only twenty-four, and Lyn twenty-one. We're still together. I finally took a B.A. degree majoring in Psychology and Literature in 1970 and became a publisher's editor in Singapore.

John Kinsella: Why poetry? When did you develop an interest in poetry?

John Tranter: When I was about seventeen. I guess most people start writing poetry in adolescence; it has as much to do with hormones then as anything. In my last year of high school a teacher gave me some poetry to read - D.H.Lawrence, Gerard Manley Hopkins, some Chinese poetry - and suggested I submit something to the school yearbook magazine. I won the prize for the best poem. Mind you, the competition wasn't that tough; this was an agricultural high school, a state-government-run boarding school, and most of the kids there were expecting to go on to a career in farming, God help them.

It took me about five years to work out what poetry was really about, and to catch up on enough reading to know the areas where I should be putting my energy. Rimbaud was my first real discovery. I latched onto him through a pulp novel based on his life by James Ramsey Ullman titled The Day on Fire, the shorter paperback version. Ullman has him heterosexual, for goodness' sake, writing love-lorn poems to a beautiful but remote girl, when he wasn't busy exploring the coffee-shops of Paris with his poet pals. I guess that's one way of explaining the poems. Then I found the Enid Starkie biography of Rimbaud, and then the Penguin Rimbaud with its sparkling prose translations by Oliver Bernard, and I was away.

John Kinsella: You're not thought of as following a particularly French line.

John Tranter: Well, no, my interest shifted to the Americans, to the poetry coming out of the USA in the fifties and sixties; all the flavours and varieties from Nemerov to Kerouac and back again. That quarter-century in the States - say the early forties through to the late sixties - seems to me a time of extraordinary energy in English writing, like the Elizabethan age, or the Romantic period.

But I was also reading twentieth-century French poetry in translation - Supervielle, Desnos, Reverdy, Michaux - and the German poet Hans Magnus Enzensberger. I've discovered with some dismay that few American poets have heard of Enzensberger. He has a profoundly ironic and richly political view of things; that's a dimension sometimes lacking in the US, I suspect.

John Kinsella: Critics sometimes mention Ashbery's name in connection with the supposed difficulties of your work.

John Tranter: Well, yes, of course I've read Ashbery; I found his writing refreshing and liberating. I think I came across it first in Donald Hall's anthology Contemporary American Poetry published by Penguin in 1962. That combination of lyrical beauty with violent formal and thematic disruption was exhilarating. His sheer intelligence is daunting too. He's almost Elizabethan, isn't he? It's no accident he borrowed a title from Marvell.

But Ashbery also spent a decade in Paris, and that interest does tie in with my early liking for French poetry. I think you can make out a line of influence that weaves back and forth: from Poe in the US to Baudelaire in Paris, then through Rimbaud, Mallarmé‚ and Laforgue back into English through Eliot (an American) in London. Then another later strand, from Desnos, Reverdy and Raymond Roussel back to Ashbery and O'Hara in New York. That rather leaves the English out of things modern, doesn't it? There's Auden, of course - another American citizen.

It begins with the Gothic, and ends up with Ashbery. But Ashbery has a Gothic mode too: I sometimes detect an Edward Gorey tone around the edges of his writing. (Ashbery's friend Frank O'Hara shared a room with Gorey at Harvard in 1949.) Ashbery's interests are bizarrely wide. He's always liked the poems of Ern Malley, the hoax poet invented in Melbourne in 1943. And he's fond of the nineteenth century Scottish doggerel poet William McGonagall. (I have a Scottish Fold cat named after him.) John Ashbery once recited to me - at the end of a rather long evening - the epic McGonagall poem about the River Tay disaster in 1879. In full, and with rolling eyes and a resolute attempt at the Scots accent: a marvellous performance.

John Kinsella: What about O'Hara?

John Tranter: Frank O'Hara's a wonderful poet, though perhaps because he's less obviously 'poetic' and more apparently colloquial, he's less discussed by the critics. He's hard to draw energy from directly, because his style was so intimately attached to his speaking voice, his wit, his accent, his milieu, the brand of cigarettes he smoked. Getting his writing separated from who he was as an actual person is like trying to separate Siamese twins.

Actually there's a lot to learn from quieter poets like Elizabeth Bishop and James Schuyler, I feel. Or younger writers like August Kleinzahler or Elaine Equi. And then there are the alarming and valuable renovations from Leslie Scalapino and Lyn Hejinian and many others. There's so much range, so much variety in American poetry, you hardly know where to begin reading. Perhaps with Paul Hoover's anthology, Postmodern American Poetry (Norton, New York, 1994). You can start from there, with over a hundred poets, each unique and different, and go off in almost any direction!

John Kinsella: You have said that you want to write new and interesting types of poetry, and you work in a very diverse number of forms. Is there a specific reason behind this?

John Tranter: Naturally I want my writing to be lively; I think it's an offence against good taste to be uninteresting.

I should say that the culture I grew up in was a provincial one. It's better now, but in the fifties it was awful. You know, the dead hand of the past. I responded to that aggressively; it was the only way to break away and be myself. Part of my interest in finding new forms had to do with that.

Also, on a smaller and more personal scale, I want to keep developing as a writer, from book to book, from year to year. I don't like to see my style settle into a rhetorical stiffness like an old bowl of jelly. I enjoy challenges.

Lyn Tranter, John Tranter, circa 1969.

John Kinsella: Do you see a necessity to create the New?

John Tranter: Well, now, what exactly is 'the New'? When I was young, loose forms were new. But for an older me, a few years ago, the Sapphic stanza was new, and that's a stubborn metrical form that's been around for thousands of years. I've used the haibun, from seventeenth century Japan, adapting that to my own purposes. Now I'm fooling around with pantoums, an old Malay form. Where will it end?

Something new is usually interesting because it's new; and then when it's no longer new - so soon, so soon! - it's no longer interesting. It's unfair, isn't it? I think it's more important to do something that's interesting because it engages with something vital in human life and society. Its relation to the passing wave of fashion is not so important.

But there's nothing intrinsically evil about fashion, and it's refreshing to see new things being done. It's salutary to notice how many really excellent poets - from Callimachus to Catullus to Wordsworth to Rimbaud to Eliot to Stevens - were regarded as excessively 'new' and faddish when they began. Catullus and his friends were contemptuously labelled the 'Neoterics', that is, the 'Modernists', people obsessed with being modern, in their own time.

John Kinsella: Do you see yourself as an 'Australian' poet?

John Tranter: When I was younger I made a big thing out of my liking for international writing, poetry from other cultures. But I feel easier with the idea of being Australian as I've grown older and seen more of the world.

John Kinsella: In that case, as an Australian, how do you see Australian poetry relating to world poetry?

John Tranter: It's part of English-language poetry; a younger branch of the family perhaps. I see it as part of a diaspora of linguistic energy from the center of empire to the periphery. The British Empire, that is. The US belonged to that empire once, of course.

You see the same thing in Ancient Greece: like Sydney, Alexandria was a polyglot city-port founded as a colony and situated far from the center of empire. The figures are interesting: in the 4th and 5th centuries B.C., twenty-five authors were born in mainland Greece and twelve in other Greek colonies. After 300 B.C. (Alexandria was founded in 331) only five authors were born in Greece proper, while twenty-four were born in the colonies.

John Kinsella: What are some influences on your work drawn from other Australian writers?

John Tranter: Uh ... I haven't ever felt part of a tradition of Australian writing, though of course whether I like it or not I am, even in saying that.

I like Kenneth Mackenzie's poetry, Kenneth Slessor, many of my own generation. But a lot of what you see in the magazines these days is pretty tedious. Well, it always was, of course.

I suppose Francis Webb is our most brilliant poet, and Sir Herbert Read is right to say that Webb is (from a British viewpoint) unjustly neglected. I mean, he's as good a poet as Patrick White is a novelist, and White, partly through having won the Nobel Prize, is a well known name world-wide. Webb's poetry, for all the respect it has in Australia, is unknown elsewhere. But that's part of the problem of being a poet: you're never going to be that well-known anywhere. And being an Australian makes it worse.

We don't seem to have produced an original talent with the power or genius of say Auden, Pound, Williams, Stevens, Ashbery or O'Hara. Perhaps you need an older, a larger and a more confident society to do that.

John Kinsella: How central is Sydney to your work?

John Tranter: Until recently I hadn't thought it was that important to my writing, but in my book of long narrative poems (The Floor of Heaven) it seemed to take over, almost as a character, or a kind of weather. People define themselves against the background of their towns or cities, almost as much as their nationalities, though of course city loyalty is provisional.

Sydney affects you because of the space, the bright daylight, the sudden torrential storms, the weather - it's usually sunny and windy, with the scent of the sea in the air. Melbourne has its charms too, of a quieter kind, though it's a horribly cliquey place by comparison.

John Kinsella: Do you have a program of poetics? Is there a particular kind of poetry or an approach to poetry that you would like to see generally adopted?

John Tranter: Oh, God no! I like plenty of variety, the way it is. I used to think I had the answers when I was younger, but that was just the vanity of youth.

I try to stay open to new ideas. And I try to fill out my knowledge of old ideas, which is perhaps more important, seeing there are more of them.

I discovered Callimachus only ten years ago. I have yet to read Shakespeare thoroughly, or the Arab writers.

Then with my writing from day to day I just do the best I can, like any writer. I like to keep pushing the envelope.

John Kinsella: How do you work?

John Tranter: Some people have regular hours. I wish I could do that. I have to push myself to write, plodding through sketched lines and ideas and bad drafts until I get sick of it and stop, or until I allow myself to get distracted by the mail, or the phone, or lunch with a friend, or maybe there's some shopping I just have to do ... Sometimes a draft will come alive and I get a burst of energy, and things go right for a while. Then maybe once or twice a year I'll get caught up in a long run of work, writing maybe ten or twenty poems in a few weeks, some of which survive their further draft transformations. I rewrite a lot, and go through many, many drafts.

I seem to be creative, in a free-associational kind of way, early in the morning. Often trains of words will wander through my mind in the shower, but nothing seems to come of that. They have to be written down for them to develop into a poem.

John Kinsella: Do you write with a pen?

John Tranter: Sometimes. I like fountain pens, but it's hard to find a good one, and it seems impossible to find a good permanent waterproof ink that doesn't attack the plastic part of the pen. Better plastics, that's what we need.

John Kinsella: What about computers?

John Tranter: I've always felt easy with computers, and I've used one as a word-processor since the mid-eighties. It's a wonderful luxury, like having a secretary always on hand to type out your drafts for you. I had a typewriter before that; first an ancient manual, then a beautiful old 1956 Smith-Corona portable electric. I still have that; my daughter Kirsten's minding it. It has a nice touch, though the motor's a bit noisy.

John Kinsella: How does the way you make a living live relate to how you write?

John Tranter: Well, I've been a student, and I've worked in different jobs, and I've been unemployed and on the dole - that was a terrible experience, to be honest. And I've had time on grants and fellowships. I should say that full-time employment, especially creative or demanding work, kills my poetry. I need plenty of daydreaming time to fill up the reservoir, and I've been extremely lucky to have been given so much writing time through the fellowships offered by the Literature Board of the Australia Council, and by the Australian Artists Creative Fellowship scheme. I've had about fifteen years of subsidised writing time, and it's meant a lot to me.

John Tranter and Lyn Grady, Nicholson Road, Old Delhi, 1967.

I've been writing for thirty-five years now, and the twenty or so years I've spent either studying, or earning a living working for other people, they were useful to me. But the writers' fellowships are vital.

The Australian government is remarkable in that way; there have been few societies that have treated their creative artists so well in terms of fair, democratic, generous, hands-off, long-term support. Australians are sometimes embarrassed to be reminded how much they like poetry and poets. We put Henry Lawson, a working-class poet and fiction writer who died of drink, on our ten-dollar note, and later the radical poet Mary Gilmore and the conservative poet A.B. ("Banjo") Paterson.

John Kinsella: That confidence about high culture, and support for the arts, that's a comparatively recent thing in Australia, isn't it?

John Tranter: Yes, for many years we internalised a British view of ourselves: we believed what they told us, that we were a simple-minded bunch of colonial hedonists with awful accents, good at golf and tennis and not much else. We're now beginning to see how self-serving that caricature is for the British; how it allows them to feel superior to what is after all a more energetic society, a society with a future, rather than a past.

As far as literature is concerned, it's a fact that we buy and read many more books and literary magazines per capita than the English or the Americans.

I have many friends in England and in the United States who are writers. Some of them have support from universities or from arts grants and foundations, but it's not an easy life for them. They have to work hard to survive in what seems to me to be an uncaring society, and they don't have that much energy left over for their art. I admire their spirit. Sometimes I don't know how they keep it up.

America at least has a tradition of patronage. It works through philanthropic foundations: the Lannan, the MacArthur, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest, these organisations have helped writers greatly, but not as a matter of government policy. In Australia it's done with the support of all the Australian working people, taken from their tax and given to those who need and deserve it. Writer's grants work out to about a dollar per taxpayer per year. That's not much, is it? You'd think every society could afford that. In the US it's more chancey; as a writer you depend on someone's generosity.

John Kinsella: I'd like to turn to a concern that many writers and critics seem exercised by at present: postmodernism. Do you think a knowledge of postmodern theory is necessary for a contemporary writer?

John Tranter: No, not really. Of course it's a good thing to be aware of the philosophical currents of the time, particularly when they deal with how art and theory are created and consumed, but it isn't necessary for the art. I mean, it doesn't tell you how to make better art.

John Kinsella: I agree.

John Tranter: Perhaps architects have to be more aware of it, because architecture is a fashion-driven trade, like interior decorating - could we be rude and call architecture 'exterior decorating'? - and postmodernism is the current fashion. Well, that's not quite true; the geographer Jane M. Jacobs talked to me in Melbourne about the new fashions in building design in Europe, the work of architects like James Stirling, who strongly denies he's a postmodernist, and Norman Foster and Nicholas Grimshaw, who appear to be driving away from postmodern trends towards something else. Their work sounds to me a little like a return to the Bauhaus; back to the future with machine modernism and functional design. But then, that would be a postmodern strategy too. Is postmodernism inescapable? It seems so.

John Kinsella: There's a lot of talk about the borrowing and mixing of styles in postmodernist works. Pastiche, that sort of thing.

John Tranter: Well, architects use pastiche - it sounds like a brand of glue, doesn't it? - then movie-makers use montage, writers and artists and primitive shamans use bricolage - gluing things together. The word 'collage' is from the French word for 'glue'.

You see it for example in James Joyce's Ulysses, where Joyce borrows forms - the stage play, the music hall, the romantic novelette. In a sense he's parodying them, but he's also using them. And you see it in Eliot's 'The Waste Land', and in Pound's Cantos. It's a tactic of classical modernism.

John Kinsella: And postmodernism - what are its tactics?

John Tranter: Well, I think postmodernism is perhaps more a way of viewing and talking about the production and reception of art, and the way art-making strategies developed over the last century, particularly since classical modernism lost steam around the time of the Second World War. I can't see it relating much to a way of making art. Few of those who do make art or literature care much for the theories that prop up postmodernism, and artists and writers are often hostile towards intellectual theories anyway. People who make things usually work with concrete nouns. People who make theories usually work with abstract nouns, and there's no way the two dialect groups can understand each other.

Let's look at Pound, Eliot and Joyce - now they may have known exactly what they were doing in, say 1922, the year in which both Joyce's Ulysses and Eliot's The Waste Land were published (and Wittgenstein's Tractatus, for that matter); after all, they were presenting the signal works of the modernist project in literature to a bewildered audience. They knew what modernism felt like down in the engine-room: they were stoking the boilers.

But did they know where the ship was headed? I doubt they would have been able to understand the terms we use today to talk about modernism. I mean, in some ways Eliot's great critical contribution to the twentieth century was his rehabilitation of John Donne and Virgil, for goodness' sake! Could Picasso have seen Pollock on the horizon in 1922? Or Stravinsky, John Cage? No way. Those people were each more concerned with the making of individual works, and the politics of publishing in the magazines of the time, and how to respond in a 'modern' way to late Victorian and Edwardian art forms, and the need to get a job and pay the rent, and so on. And they didn't know that they were creating the signal works of the modernist project in the way we understand that project now; Eliot was trying to get a poem published, and over in Paris James Joyce was thinking about his next book, and a pair of boots he'd asked someone to send him from England. [ In fact, they were an old pair of brown shoes belonging to Joyce which Ezra Pound had parcelled up with some other clothes and given to T.S.Eliot to pass on to Joyce in Paris in the summer of 1920, according to P. Wyndham Lewis, Blasting and Bombadiering (1937; 1967 edition) pp. 267-69. Calder and Boyars Ltd. - J.T.]

John Kinsella: Is there a quality in a work of art that we can call 'postmodern'?

John Tranter: I'm not sure that it's in the work of art - hovering behind it, perhaps, or glowing like an electrical spark in the air, jumping the gap between the work of art and the consumer. I suppose that 'postmodernism' might simply be the quality - almost magical, mostly invisible - that tells the theorists among us that certain artworks or cultural constructions - television game shows, for example - are responding to the postmodern condition of the world; or of the art world, or the world of intellectual discourse.

I guess it's an issue, just how 'responsive' a well-behaved art work should be to the condition of postmodernity; or how 'willingly' a good art work should present itself for scrutiny of this sort, which is often derived from a Marxist analysis of society and culture.

John Kinsella: Does that relate to so-called 'language' poetry? Some of the thinking behind that seems allied to Marxist analysis.

John Tranter: So-called 'language' poetry seems to me to be a mixture of linguistics, Californian Marxism, Gertrude Stein and French literary theory. Lyn Hejinian said (in a talk in Sydney) that it came out of her generation's responses to the official lies and propaganda the Nixon government used to justify the Vietnam war. It seems that in one sense those young people wanted to purify the language that had been contaminated by their parents' generation. And it developed from that, over a couple of decades, and woke up one day to find itself corralled by academia. It's perhaps the first time a literary movement has been developed by young university-trained critics who have written the creative texts required by the theory they developed. Perhaps that's why some readers find the texts somewhat lacking in the pleasure department.

Some of this theory can be useful when it explores and exposes how value in poetry is constructed by the people who consume it, and then shows how this ideological process is denied and concealed by the consumers. That's interesting.

But a culture's desire for poetry is difficult to analyse in a Marxist sense as a 'commodity'; it functions outside the relations of capital in many important ways, unlike say architecture, which is linked to capital by an intravenous tube with a pump at the other end. And a critique of poetry as 'commodity fetishism' can't say much that's useful about how poetry actually works - how it has functioned since the bronze age.

Critics don't seem to deal well with 'role' in that sense. I'd like to see a theory of poetry that talked not about 'value', or 'voice' or 'stance', but 'role' instead: drawing on Erving Goffman's work in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, perhaps. That kind of theory could usefully look at Shakespeare, at Browning's dramatic monologues, at Auden's various roles, at Stevens, at some of Frank O'Hara's games with 'I' and 'you' and role-shifts and reversals. I think it's time we let Gertrude Stein have a rest.

John Kinsella: Would you accept that you've written some of the more important Australian postmodernist texts/poems in the last few years? Especially in your 1988 collection of poems Under Berlin, in The Floor of Heaven in 1992, At The Florida in 1993, and the material published in journals since then?

John Tranter: Picasso is supposed to have said that one should not be one's own connoisseur. It's not for me to talk about the importance of my work; that's up to other people. I guess though that my writing seems to have been responding to the postmodern condition, for what that's worth.

John Kinsella: But I gather it wasn't conceived as being postmodernist when you were writing it?

John Tranter: Back in 1964 the poet Lee Cataldi said I should read Ferdinand de Saussure, the linguist whose lectures in the early years of the century more or less started the fashion for structuralism among French academics. I tried, but I found it too dry and technical, and as far as linguistics went I was more interested in Chomsky, and then in Benjamin Lee Whorf and Sapir, who were on a linguistics course I was doing. They had clear and intriguing things to say about how a culture forces one to see reality in certain ways, ways of viewing things which are relative to different cultures and which are essentially linguistic.

In my own writing - and in the reading I did to discover how to write - I was interested in exploring European modernism, which believe it or not felt like a daring new thing in Australia back then, and in Freud and Jung, in relativity theory, in movies, in various other new types of poetry.

I would also say, as a minor point, that postmodern writing appeared in Australia in the late sixties and through the seventies as a result of our trying to come to terms with some of the strategies of late classical modernism. In other words, by the time modernism arrived here to any real effect, it had transmuted into postmodernism. In a TLS piece a few years ago, the critic Lawrence Norfolk says that 'Modernism met its match in Australia ...'. He says it was 'A succession of short-lived attempts, never quite a movement.'

John Kinsella: I dislike the expression post-post-modernism, but don't you think in the long narrative poems collected in The Floor of Heaven you're setting up a straightforward construct in terms of dialogue and monologue, and then you're stretching it, making it taut? Is the term 'post-post-modernism' relevant here? And do you think you can be humane, or humanist, and post-post-modernist?

John Tranter: Well, I suppose The Floor of Heaven could be seen as a post-post-modernist project, but I didn't set out to do that. I just do what I do, and when I turn around and look at it afterwards, that seems to be a category that might fit.

As for incorporating humane, or humanist values, in contemporary writing - that seems a worthwhile challenge. I think it's always true that writers need to do work that's interesting in itself as craft and art, in terms of where the art has developed to, as well as having something of human worth to give people. You should be able to do both; why settle for less? You only have one chance at it. You need to keep a light touch, though. Humanism has been contaminated by a thousand bad poets who demand that poetry be Deep and Meaningful, the D&M Squad of the Salvation Army, who take moral earnestness as a mark of quality, but humanism can't be blamed for that.

It's not compulsory, but I think the best artworks give you both a fresh handling of materials, the techniques and themes of the contemporary world, and at the same time they give you a little more - a glimpse of human fate and destiny that the reader can project back into the work. We each have to die, and that's important; and no amount of theory will mediate that.

John Kinsella: Let's talk about The Floor of Heaven for a moment. It's almost like a collection of four novellas, isn't it, adding up to around a hundred and forty pages of blank verse. They're mainly about strong women characters, although there are some interesting men as well. Now despite the language of those poems - those narratives - being somewhat removed from everyday life, it still operates on a humane and familiar level, wouldn't you agree?

John Tranter: I wanted the language to be reasonably naturalistic, though perhaps a little feverish. And because it constructs 'believable characters', then I guess it is operating on a level where you can talk about humane values and so forth. Actually those narrative poems owe their style more to Christina Stead's short stories than to anything else, particularly her use of monologue as a narrating device. I was very impressed by her novella Girl From the Beach when I read an extract from it - this was in the mid 1980s - in the Winter-Spring 1967 issue of the Paris Review. It's mainly monologue, that rushes along and carries you with it. Stead was interested in people just as much as she was in literature, whatever that is. More so, I think.

John Kinsella: What about the violence, the extreme emotional states, the tides of passion that seem to wash back and forth through The Floor of Heaven? Are we dealing with melodrama here?

John Tranter: (Laughs.) It's funny, some critics have read the poems as critiques or parodies of classical melodrama, if you'd allow the oxymoron. I'm not so sure it's as cynical as that, or as simple as that. I confess the action is sometimes lurid, and the emotional currents rather high-voltage, but I wasn't consciously setting out to parody that style of narrative, really. Perhaps I'm not as subtle a writer as some people think. I wanted to jump into the action and get moving, 'in medias res' as the poet Horace says. And the characters, their extreme emotional states - well, I've never been interested in pale, self-questioning nerds like the Bloomsbury set, sitting on the terrace in the twilight sipping cups of tea and talking about spiritual experiences. I like characters with a bit of bite, who have a 'rage to live', to quote a Suzanne Pleshette movie title.

You see, the story is built on spoken monologues, so the people speaking have to have something compelling to say, or the reader is going to lose interest. I used to work in radio - radio plays - and one rule in writing radio goes like this: you have to grab your audience right at the start, and keep them interested. If you lose the listeners in the first five minutes, you've lost them, period.

John Kinsella: Could you discuss the correlations between narrative in your poetry and that in film?

John Tranter: Film usually works through narrative. There have been exceptions; I'm thinking of a colour short titled NY, NY back in the sixties, a piece about half an hour long that featured distorted reflections of New York, reflections in hub-caps and rippling pools of water, with a jazz sound-track; and of course there's the fashion photographer Bert Stern's Jazz on a Summer's Day, a bright and 'poetic' documentary of a Newport jazz convention in the late fifties. But film depends, in terms of economics, on audiences of a certain size, and they have an appetite for narrative, and essentially narrative that embeds characters in a plot; a plot that constructs the responses of the characters. So most movies are rather like novels; long and narrative.

I think most contemporary 'lyric' poetry is more like that short film I mentioned, NY, NY - selective, colored, distorted, without a linear time-frame, and with a few small but intense points to make.

Those long narrative poems in The Floor of Heaven are different - They're perhaps more like conventional movies, in terms of scale, duration, narrative approach. You can read most contemporary lyric poems in about five minutes - you get one quick thrill, and that's it - but 'Rain' (one of the narratives in The Floor of Heaven) is forty pages long, and it has characters and a storyline, and scenery - and even a sound-track, if you listen closely.

Film - I love the way the language of film can be so vivid, yet seem so natural. And with the advantages of a sound-track, good-looking actors, makeup, lighting - any poet would be envious of that grip on the audience. Sometimes I think that my poems are my attempts at film.

John Kinsella: What about video? Is it the medium of the future?

John Tranter: Hmmm ... maybe the bright young things today are making videos instead of poems. Perhaps that's the artistic medium we should be watching.

But then video is soaked with the values of advertising. To make an arresting video clip you have to make it look and sound like a good television commercial. Commercials have the qualities of a successful prostitute. Look at Madonna's video performances: about as deep as a Wettex®. It's all a come-on, and the energy derives from greed. Who wants that?

John Kinsella: Looking at the reception of your work generally, how do you feel about the notion that your work is going to be interpreted in a theoretical context, as opposed to the lyrical mode, in which most poets have been examined? Do you see academic-based theoretical analysis as an appropriate way of looking at poetry?

John Tranter: Well, on the one hand I can't do anything about that, so what I feel about it doesn't matter. It will happen anyway, and that's fine. On the other hand, I think that what I write will test the critic as much as the other way around. So I find that interesting too. And as for lyricism, while I'm emotionally drawn to it, there's so much opportunity for fakery and bullshit in that mode, that it's a good thing to see it tested by theory.

John Kinsella: With some poets like Yeats, say, there is an over-riding concern with the notion of vision. You on the other hand seem more concerned with the possibilities of language as a thing in itself.

John Tranter: Not really. In my early work I was very interested in the idea of vision. My first book was titled Parallax, a word that relates to camera viewfinders and binocular vision. On a more complex level, language itself constructs the way a person perceives and constructs the patterns in the world around them. Gestalt theory still has important things to say. Language is obviously the crucial factor in a piece of writing, and I've been interested in it from a linguistic point of view, and from a philosophical point of view, and peripherally from an anthropological point of view, because that's what determines your vision, what you can and can't see of the world. I'm interested in language because it's what poems are made out of.

John Kinsella: What about 'vision' as a metaphysical concept?

John Tranter: Well ... I've always had a religious tendency, though I don't usually talk about that much. In my twenties I read widely among a number of religions, and put some years of study and practice into Zen Buddhism. I respect Zen as a philosophical and psychological system, and the general Buddhist theme of compassion seems a good thing, when you look around you.

Wittgenstein said that 'of that which we cannot speak, we must remain silent'. What he didn't realise - apparently he didn't come across any Zen teachers - was that such things do have meaning, are vitally important, and can be communicated. At a certain level, you have to go beyond language. In fact it's the dualistic nature of language that's the problem with the way we perceive the world, which in itself is not dualistic.

There's an old saying that those who know do not speak, and those who speak do not know. Somehow writing poems about these delicate and paradoxical matters seems not only stupid - logically stupid - but tainted with vanity and bad taste as well.

John Kinsella: Do you think the poem can exist as an object it itself?

John Tranter: Well, yes, of course it does. Look at little children who repeat nursery rhymes. They have no idea what the meaning of 'Humpty Dumpty fell off the wall' is - I think it was originally an English political satire - but they know it sounds good. It's a delight for them. We should keep in mind, I think, that the aim of poetry is delight.

On the other hand, a poem only has meaning because of the history of the language it's written or spoken in, and the broad culture and the literary traditions of the society it operates in; so on a level of linguistic function, all its meaning is conditional and relative, and changes over time, and with different readers.

John Kinsella: [The Australian poet] Les Murray is a slightly older colleague of yours. How do you view his work in terms of the way it uses its language?

John Tranter: Oh, Les has a linguistic talent, a real way with words. In his writing I think he tends to take the solidity and denotative abilities of language for granted as a tool he can put to good use. Not for him the modernist doubt and angst of Beckett, say, or Finnegans Wake. He just gets on with the job, describing a landscape, or two farmers talking, or an animal's interior thoughts. In some ways I think of him as having the combined talents of an Edgar Lee Masters and a James Dickie.

Then there's another decorative and riddling way he uses words, rather like Craig Raine's 'Martianism', where you get things displaced into metaphors and made strange, and you have to guess what it is he's describing, like the mystery sound effect in old radio shows. It's an example of what Viktor Shklovsky called ostranenie, a process of deliberate 'enstrangement', of making the ordinary seem strange. It's also related to 'kenning', an ancient Scandinavian poetic device, and quite attractive in small doses.

Readers who like Les's work tend to invest in the general belief that if a writer says a particular thing memorably enough, invoking 'literature' to authenticate the poet's 'voice' and vice versa, then the words take on an almost magical weight, a gravity, that guarantees the broadly moral or religious values underneath the statement. It's that Deep and Meaningful thing. I tend to think with Saussure that words are a little more fragmented and arbitrary than that. And then there's the dangerously circular nature of that 'vice versa'. You can end up authenticating yourself, endlessly, and sounding like a radical clergyman.

But then Les and I are more alike than different. we're both contemporary Australian poets, with Scottish ancestry, from coastal country farms, who both attended Sydney University during the sixties, married during the sixties and had children, studied Arts, failed some subjects and dropped out, and came back a few years later to complete our degrees. Perhaps we were twins, separated at birth. (Laughs.)

John Kinsella: A few years ago I heard a program on Helicon [a weekly arts program on ABC Radio National] on the poet Harry Hooton, a poet who was born in London in 1908, migrated to Australia in 1926 and died in 1961. What did you have to do with that?

John Tranter: That was produced by two writers, Amanda Stewart and Sasha Soldatow. I commissioned it when I was in charge of Helicon, in 1987 and 1988.

John Kinsella: How do you feel about Harry Hooton as a poet and individual?

John Tranter: I feel sad that he wasn't as good a poet as he hoped he would be. I admire his non-conformist spirit and his bohemian stand. I just wish he'd been a better writer. His ideas were interesting, like many of the ideas of the Sydney 'Push', the intellectual mob he hung around with. In their time in Australia, in the nineteen-forties and fifties, his theories - which were related to Futurism, in a way - were startling. I don't think there was anyone quite like him. But I think he lacked either the gift to write well enough, or the willingness to train himself to do it.

John Kinsella: You were quite sympathetic though, during the Helicon program.

John Tranter: Well, I felt it was important that what he did be remembered, and I thought it made good radio. Radio is a wonderful medium for remembrance - that direct speech is a potent effect. So for lots of reasons I wanted it to happen.

John Kinsella: Some reviewers have called your early work remote, or cold. Cavafy removed himself from the immediacy of his own life through his use of myth and history. Do you think you've done this in an intellectual way, through language?

John Tranter: Perhaps I have. Cavafy had to withdraw a little from his material for all sorts of reasons. He was writing at the turn of the century in the city of Alexandria, in Egypt. He was often unable to be frank about what he was discussing - male homosexuality, much of the time - but also I think there was a natural reticence that heightened the intensity of the experiences underneath or behind the poem, and that's what I like about his work. I grew up an only child, on an isolated farm, and I'm rather shy as a result; I can relate to that, that kind of double effect where you say: 'I'm not really affected by these things', and yet the way you say that implies that actually you are. I think you get a stronger response from the reader.

I've always disliked gush. Perhaps in my early work I went too far the other way, so that some of my work ended up sounding cold or cynical; I don't know. I did the best I could. Something I've realised only lately is that every writer does the best she or he can. There's no use saying 'Oh, I wish Graham Greene would stop going on about his Catholic angst', or 'I wish Henry Miller would stop writing about his dick.' They were doing their best. They couldn't do any better.

John Kinsella: How close is your poetry to your life?

John Tranter: Uh - fairly close, but it depends on the poem.

John Kinsella: Whereas a poet like Robert Adamson is totally and utterly involved in the evolution of his poetry and the evolution of his life. They are synonymous.

John Tranter: Ah ... well, that's what he says; you can take that or leave it. Have you met Robert Adamson? He's a very complex man. And under-rated as a poet, I feel.

I'd say his life and his poetry are separate things; but I could be wrong.

For me it depends on the poem. Occasionally I write drafts of poems that are based on linguistic play, and that might turn out to have some interesting material. I develop them a little more, and if I like them I publish them. With some other poems, I find I'm writing about experiences like the ones I've had in my own life that are important to me. And so, some of my poems are deeply personal; while others are quite impersonal. And some - the best, perhaps - are a little of both. It just depends on the individual poem. I write so many different kinds of poems. It must exasperate the critics.

When I was young I was influenced by T.S.Eliot's theoretical writings as well as his verse. He talked about the removal of the personality from the poem. Frank O'Hara talked about the same thing. O'Hara's poetry is personal, and it has a lovely touch - like the touch of a good pianist - because it is apparently impersonal, and he manages to do that trick of having his cake and eating it too.

John Kinsella: Another tangent. Do you have any admiration for the compression of image? How do you respond to the idea of 'deep imagism', the sort of thing you see for example in the work of the American poets Robert Bly and Galway Kinnell?

John Tranter: I learned a lot from Bly. Poems like 'Awakening', 'Driving toward the Lac Qui Parle River', and 'Sleet Storm on the Merritt Parkway', these are classic works, and immensely seductive: passionate, yet cool; thrilling, yet beautifully articulated.

But I don't know ... they seem to take the concept of the lyrical moment for granted, like Cartier-Bresson's idea of 'the decisive moment' in photography. If a master does it, it seems to be true; and Bly and Cartier-Bresson are masters.

Yet when you analyse that remark of Cartier-Bresson's, there's no theory there at all, just a simple classroom skill. If you're using a camera, of course you wait for the decisive moment - or for the next decisive moment, if you miss the first one; what else would you do?

Whenever I think of Galway Kinnell's audience I think of constructions that are strangely insincere. Not that he is, or that his poetry is: he's a very earnest man. I'm talking about the collective representations created in the space between author and reader, a kind of cultural hologram, created by the desires of the consumers. It seems that a lot of middle-class middle-aged Americans have a belief that if a poem appears to come from an intense and profoundly stirring experience, like fighting to the death with a grizzly bear, then it's a deeply meaningful poem - that D&M stuff again! - which will recreate in themselves a corresponding emotional state. They consume National Geographic magazine or movies like Dances With Wolves for a similar reason: to enjoy a kind of anthropological tourism. But perhaps I'm letting my congenital Australian cynicism corrupt my responses. I like Galway's poetry. He has a great verbal talent, but his work sometimes seems to be acting out a role that fulfils a set of audience expectations that I would find somewhat confining.

John Kinsella: I'd like to focus on poetry by Australian women poets for a while now. Who do you think the major women poets are? What do you feel about the 'development' in women's verse in the last twenty or so years, and within the context of the 'Generation of '68', that large and energetic generation of young Australian poets who began publishing in the late 1960s?

John Tranter: I think perhaps a woman would be best able to do that, but for what it's worth I'll talk about it. To start with, there are heaps of good women poets in Australia, and you can find most of them in the Penguin Book of Australian Women Poets, not to mention the Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry, where a third of the contributors are women. A decade ago my wife Lyn and I published with our own hands and with a very helpful printing subsidy from the Literature Board, Gig Elizabeth Ryan's first book, and Susan Hampton's first book. I still like their work; it's vigorous and it's varied.

Among the other women poets whose work I really enjoy are Judith Wright, Dorothy Hewett, Antigone Kefala, Jennifer Rankin, Lee Cataldi, Joanne Burns, Vicki Viidikas, Pamela Brown, Anna Couani, Jennifer Maiden, Ania Walwicz, Dorothy Porter, Judith Beveridge, Kate Lilley, Meredith Wattison, Lisa Jacobson ... it's a long list, really, and there are many others I could mention.

As to why there were fewer women poets than men poets among the people whose work developed strongly in the so-called 'Generation of '68', it's hard to say. Those things happened nearly a quarter of a century ago, now. I'm no sociologist, but I have a half-serious theory that the heavy social, cultural and educational pressures through the first half of the century, and especially in the 1950s, produced a generation of young Australian women who saw their role in life as domestic, co-operative, non-competitive, and supportive of men. Australian boys on the other hand were taught to be competitive, individualistic loners, able to forge ahead and put up with years of struggle and obscurity, working on projects which others thought peculiar but which they obstinately gave value to; like [the aeronautical pioneers] Lawrence Hargrave and Kingsford Smith. We put them on the twenty-dollar note. Think of the early explorers who were held up as models in Australian schools: Matthew Flinders, Burke and Wills, Leichhardt; and the movie heroes: Scott of the Antartic (the doomed hero of the first movie I ever saw), Chips Rafferty, John Wayne - stubborn individualists, all of them.

Competitive individualism and stubbornness are the opposite of the qualities people imagine poets are born with - sensitivity and empathy, you know, that blend of Keats and Bambi. But perhaps competitive individualism and stubbornness are the very qualities you need to survive and endure over time in Australia, slogging away at the unrewarded profession of poetry for long enough to get good at it.

Perhaps most young women had too much sense to slog away at poetry. Only a tiny proportion of any generation of writers is going to succeed, and lack of success in that field left a lot of young men miserable, unemployable, and generally strung-out.

Of course the women's movement through the seventies and eighties gave support and direction to a lot of women poets, and you can see the results in the writing; some good, some not, like most writing in any age, but by comparison stronger, more individualistic and better-developed than before.

Though we must remember history. In Australia, as in England and the US, women have always been successful in the field of fiction, in short-story writing and novel writing, and they've done well at that for over a hundred years. In the early 1990s, more than three quarters of Penguin's top thirty best-selling Australian fiction titles were by women.

John Kinsella: Do you think there are cliques within publishing circles in Australia?

John Tranter: Well, not really, except that writers tend to become friends through a magazine, or to a lesser extent through a publishing house. They're like a local pub, in that sense. The word 'clique' gives a wrong sense of conspiracy to the thing.

For example, there was supposed to be a sinister clique dubbed the 'Brisbane Octopus' in the early 1970s. David Malouf, Rodney Hall, and Thomas Shapcott were friends, and all came from Brisbane (or from nearby Ipswich in Tom's case) to Sydney in the 1960s (Tom stayed behind for a few years), and became involved in poetry magazine, newspaper and anthology publishing, reviewing and editing in various powerful and complex ways. Tom even became Director of the Literature Board, though that job gives you more ulcers than power. Some young poets said they had a stranglehold on the new poetry, but in fact they helped many poets find publication, notably Dransfield and Adamson at the start of their careers. They encouraged lots of young people, and what I remember about each of them was their enthusiasm for the work of young writers, and their generosity.

Then there's a contemporary grouping that includes Les Murray, literary editor of Quadrant magazine, set up in 1956 by James McAuley as a means of countering the influence of international communism on intellectual life. It was supported financially by the CIA for many years. The previous literary editor was Vivian Smith, and for many years Vivian and Les Murray were the two poetry readers at Angus & Robertson Publishers, our leading poetry publisher then - they more or less decided who could be published there. Dame Professor Leonie Kramer is on the Quadrant board, and she was Vivian Smith's superior at Sydney University's English Department for many years. She was the chief editor for the Oxford Australian Literary History, for which Vivian Smith wrote the poetry section. And of course Les Murray edited Oxford's major anthology of Australian poetry, and he was also the chief advisor on the modern poetry entries in the first edition of Oxford's Companion to Australian Literature. When Les was editing Poetry Australia magazine in the 1970s, his friend Jamie Grant wrote a few rather ungenerous reviews for the magazine of poets whose work he and Les didn't like. Jamie Grant's poetry has appeared in Quadrant for some twenty years now. With his wife he's the publisher of Isabella Press, which publishes Les Murray's poetry and the poetry of a group of poets who left Angus & Robertson with Les a few years ago, after Les had a disagreement with the new management. Jamie Grant's Isabella Press books are actually published and distributed by Reed/Heinemann, where Jamie Grant's brother Sandy Grant was chief executive for many years. Jamie Grant's wife is Margaret Connolly, and she's Les Murray's literary agent.

And so it goes, around and around - probably the most complicated set of interrelationships in Australian literary publishing ever, and I suppose some people might call it a clique.

But as far as I know they're just people who've become friends because they have common likes and dislikes. I'm sure there are other groups of friends like that all over Australia, supporting each other's work - some left wing, some right wing, some radical, some supporting a conservative tradition, some in the middle.

I think it often goes like this: if a group of people want to publish your next book, They're your friends. If they don't want to publish your next book, They're a clique.

John Kinsella: You mentioned tradition. When people talk about poetry they often focus on shifts in tradition, or style, or form. The formalist debate is strong in the US now. Where does content come into this?

John Tranter: I think that 'content' is an important problem of modern poetics, one that's not talked about much. Is the desire for content essentially middle class? Can you get rid of it and still have literature? I think Gertrude Stein tackled it, I think Ashbery was addressing it in a different way in his early book The Tennis Court Oath. That's the book so many people, including me, find hard to read, but that's the point in some ways. You could say that the Iowa Writing School poets take it for granted that there's no such problem: as a poet, it's your job to write about the Deep and Meaningful stuff - anguished relationships, deeply moving climatic conditions, momentous landscapes, small but perfectly formed epiphanies of the bourgeois life.

The so-called 'language' poets take the problem as their main focus - what actual quality of language makes this group of words a 'poem', this a clever concoction, and this a valueless piece of trash? What happens if we turn them inside out, or mash them up together?

Form and content are traditionally supposed to work together to create meaning; but we're now beginning to see that meaning is constructed by the reader as much as by the writer, and that it's constructed by the society, and by the complicated and powerful traditions of writing, editing, publishing and marketing, as much as by the individual reader. And then there are the writing schools!

For a year or so I was interested in a text-generation computer program which reconstructs a piece of text from any sample you might care to feed into it, using a statistical analysis of letter-group frequency arrays. It's too technical to explain here, but the program can imitate the texture of a particular writer's work, without imitating the meaning in any way, by reconstructing a text with the typical sequence of letters the writer tends to employ. The content is - well, there isn't any, it's a blank, because nobody meant any of it; nobody wrote it. The computer merely assembled it. So you can have style - style so pure you could say it's been sterilised - uncontaminated by any considerations of content. And yet as a reader you're constantly scanning for meaning, for content. That's what makes writing readable. Fascinating.

John Kinsella: What about the long narrative poems that make up The Floor of Heaven? Did they begin as computer experiments?

John Tranter: Oh, no, quite the opposite. I wrote them as straightforward narratives. In fact my adventures with narrative verse began as prose, as drafts for a chapter of a novel which I never went on with. I seem to do that every five or ten years.

John Kinsella: You completed Under Berlin in 1988. What did you work on after that?

John Tranter: I worked on the long narrative poems for about five years, I guess. At the same time I was writing quote normal unquote poems from time to time. I compiled them into the collection At The Florida, which appeared in late 1993.

It contains a mixture of things, including a sequence of thirty "haibun", which are poems each about a page long. I was looking for a new form, trying to wade out of the tar-pit of habit, at the same time as I was looking for a way of avoiding the patterns of meaning that the forms of verse themselves impose on a piece of writing. The "haibun" was developed in seventeenth-century Japan, and consists of prose and verse mixed; traditionally a short prose passage is followed by a haiku. I have inverted and re-engineered the form for my own purposes, settling on a twenty-line stanza of free verse, followed by a paragraph of prose up to half a page long. One of the haibun - 'The Duck Abandons Hollywood' - actually started out as Wordsworth's 'Daffodils', would you believe. I put it through the wringer and Wordsworth's line 'a poet could not but be gay' came out as 'a troubadour could not but be / bisexual' which says something about how times have changed, if nothing else.

Then there are fifty or so pages of various pieces. Oh, and two rather long poems in Sapphics, one in loose and one in regular Sapphics. One has appeared in the Paris Review and one in Parnassus: Poetry in Review. Sapphics are interesting to work on; it's a particularly obstinate form in English though no doubt it works fine in classical Greek.

John Kinsella: Semantically, how do you view language structure in your poetry? I'm particularly interested in the new, shorter forms you are using and how this implicates content in a theoretical context.

John Tranter: With modern poetry there's always a tension between the older formal structures - it's amazing how much energy the sonnet and the iambic pentameter still have in English, and alliteration is perennially energetic - and newer looser structures, particularly demotic and colloquial forms.

With my 'haibun' poems, I guess a reader would find a simple tension between the twenty lines of free verse which make up the first stanza, and the prose that makes up the second. They have different rhythms, different densities, and in a sequence of them, you might find a tightening and loosening effect as the verse and the prose alternated, like waves on the ocean. Then in those poems there's a different tension, between varying kinds of content: old-fashioned content on the one hand, where meaning lies in description or argument or tone, and an apparent denial of content on the other, where meaning seems to be contradicted, disrupted, fragmented and eventually denied. But I guess that's not answering your question very well.

John Kinsella: As well as writing your own poetry, you've also done a lot of other work in the field of anthologising, compiling books and radio programs ...

John Tranter: I worked as a radio producer with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation at various times over the years, producing programs on history, archaeology, a documentary on carnival sideshow workers, interviews with poets and critics, and radio anthologies of poetry from Sir Thomas Malory to Frank O'Hara and John Ashbery.

The latest print project I'm excited about is the Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry, which adds up to nearly five hundred pages. I worked on that with Philip Mead as my co-editor for two or three years, and it's been published now, to mixed reviews. I think its most interesting feature for the reader is the inclusion of all the poems of 'Ern Malley', a hoax figure concocted by two young conservative poets in the 1940s as an attack on the pretensions of the experimentalist and Apocalyptic schools in Australian verse. That book has been published in the UK as the Bloodaxe Book of Modern Australian Poetry.

John Kinsella: You've been involved in two other anthologies as well, The New Australian Poetry in 1979, and The Tin Wash Dish for ABC Books in 1989. What are your views on the poet as anthologiser?

John Tranter: Well, for a start, anthologies are always acts of criticism, and that's interesting, because criticism at its best is a dialogue, a way of talking about the art form that invites responses. The word 'anthology' comes from the Greek, and means a collection of flowers; the corollary is that you leave the weeds to wither. Sometimes readers need a little help in picking the flowers and leaving the weeds aside. (I'm joking.)

Anthologies also preserve poems. So many poems simply disappear into the maw of the past, and anthologies are perhaps the best way of preserving them for future generations. We'd have no Callimachus and no Sappho if other people hadn't anthologised, quoted and argued about their work. Their own collections didn't survive.

Of course when you have a poet anthologising other poets, there are dangers. For example in Robert Gray and Geoffrey Lehmann's anthology The Younger Australian Poets, the three poets with many more pages than anyone else were Les Murray and the two editors. But I don't think anyone was particularly worried about that. I suppose there's a danger that the poet will be partial to her or his friends, or will exclude someone she or he personally dislikes; but any honest person will try hard not to do those things. A critic or an academic scholar is just as apt to be biased in any case; look at The Oxford Anthology of Australian Literature. That was supposedly a work of academic scholarship, balanced and comprehensive, and it turned out to be a rather inadequate collection in some areas, to put it politely, and sank without trace.

John Kinsella: You've started up an Internet magazine, in mid-1997. How did Jacket magazine come about?

John Tranter: I saw that the Internet at one stroke does away with the two main problems of literary magazines - the cost of manufacture, and how to reach your audience. Jacket is a quarterly, and I guess in print form each issue would be over a hundred pages long. It has dozens of full colour photos and pieces of art work. To print a thousand copies of a single issue would cost around ten thousand dollars, and involve half a dozen highly skilled people - typsetter, proof-reader, designer, platemaker, printer, binder, and so on. To ship it around the world and warehouse it in New York, San Francisco and London would cost even more. Yet the Internet does all that virtually for free. Well, for say a few thousand dollars. Well, once you have a computer and scanner and so forth, and the skills. It's not that difficult.

John Kinsella: It comes from Australia, and reaches the world.

John Tranter: No, it doesn't come from Australia. It doesn't come from anywhere. It exists on the Internet, as a whirl of electrons, not in Sydney, Australia. The content is international not because it wants to be "international", but because there's no sense in restricting good writing to one set of national borders. In Holland or in Hackensack, in Minsk or in Marin County, you just log on and type in the same address.

John Kinsella: Which is?

John Tranter: Its nice of you to ask, John. Jacket is free, and it can be found at http://www.jacket.zip.com.au

John Kinsella: You've said that you've always been interested in writing from overseas, from outside Australia, and you've done some reading tours overseas yourself. Do you plan any more of those?

John Tranter: I did two long solo tours through the States and Europe in 1985 and 1986, reading at around seventeen or eighteen venues each time, from Cody's bookstore in Berkeley to the Universities of Stockholm, Oxford, Heidelberg and Regensberg. That was wonderful fun, but it sure tired me out.

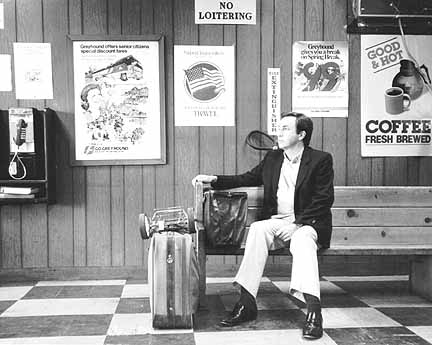

John Tranter, somewhere in America, mid-1980s.

I did a trip in early 1992, visiting the United States for some ten weeks. I had a residency at Rollins College, a quiet little college in Florida, and I did some readings in Chicago and San Francisco, and attended a conference of the American Association for Australian Literary Studies in Eugene, Oregon, where I gave a talk and a reading from the Penguin anthology.

In 1993 I was asked to talk at a conference on Australian radio features in Paris organised by the Australian radio features maker Kaye Mortley, a very gifted artist. While I was there I did a reading in the Village Voice bookshop in Paris - a tiny place, crowded like a can full of sardines, a lot of fun. And I travelled to England and the US in 1994, and again in 1996 and 1997.

You can learn so much from another culture, mainly about your attitude to your life, to your work, and to other people. And to your own culture, of course. You don't notice those things if you stay at home. You learn that these things are relative and conditional. It can give you a shock to see Australia through French eyes, say. To the French, style is the most important thing. The average French official would rather die than be seen in public in grubby gym shoes, denim jeans, and a tweed jacket. And then, the average French intellectual would rather die than be seen in a business suit. For them, denim is fine, but runners are not. They're so tense! And their books of poetry have to look just so - no illustrations on the cover, just print, centred, and only in red and black ink, on cream board. I was amused to see that the menu at the Café du Commerce in Paris is typeset and designed to look exactly like a book of French poetry. But then the French are locked into the concept of proper manners, it's like a straightjacket.

And the States ... I like the energy of the US, and the emphasis on individual freedom, but that American worship of work and success has a dark side, like capitalism itself, which makes a poor and malleable working class an essential part of the system. But so many of the American working poor want it that way - they want the system just like that, because it gives them a chance to be a success. Or so they think. I like the States, but I don't think I could live there for long.

I miss my family, with all that travelling. And the distances are hard to believe. It can take more than 24 hours to fly from Sydney to New York, and that's in a 747! I fly Qantas whenever I can; They're safe and reliable, and they usually have a very nice red wine.

This link takes you back to the main

I'd like to thank Philip Mead and Lyn Tranter for their helpful comments.

John Tranter page "Three Poems & an Interview"

- J.T., Sydney, 1991-97

Acknowledgments: The first draft of this interview was recorded in Sydney 1991 by John Kinsella, and expanded and developed later by both participants. A version appeared in Verse magazine and later in the anthology Talking Verse, Interviews with Poets, (ed. Crawford, Hart, Kinloch and Price), Verse, St Andrews and Williamsburg, 1955.

Final revision for this version August, 1997.

This page was composed using Georgia (body text), Trebuchet MS, and Verdana, typefaces designed to be attractive and legible at all sizes on computer screens. Each is available as a free download from Microsoft on http://www.microsoft.com/opentype/free.htm

If you install them on your computer, Netscape or Microsoft Explorer version 3.0 or greater will automatically display this page using those fonts.

Back to the top of this page