The Digital Poetry Genre

Jorge Luis Antonio

From Issue 1

THE DIGITAL POETRY GENRE

Jorge Luiz Antonio

Elson Fróes (Brazil) - Orpheus

<http://www.elsonfroes.com.br/visual.htm>

ABSTRACT

This paper aims at showing a brief panorama of the poetry that circulates on computer (hard and floppy disks), CD-ROMs, Internet and sites. This poetry can be named experimental poetry, new visual poetry, digital poetry, internet poetry or new media poetry. Certainly, it constitutes a genre itself: the digital poetry genre, which appears side by side with the many other existing poetry genres (verbal poetry, visual poetry, sound poetry, and so on).

Another aim of this paper is to map the constituents of digital poetry as a genre whose discourse has been adapting itself to the digital-electronic media as a means of survival and renewal of the existing visual, sound and verbal forms. Having as a goal the delimitation of poetry in relation to other artistic digital forms, a brief report on digital poetics (also called electronic art, web-art, net-art, cyber-art, etc.) is then necessary, since it traces back, to a certain extent, the route of the word that evokes image, transforms itself in visuality, changes into infographic image, and at the same, time becomes movement.

Though not trying to establish a historical or national perspective, the proposed mapping shows a variety of names and kinds of digital poetry such as cyberpoetry, computer poem, infopoetry, hyperpoetry, interpoetry, virtual poetry, digital poetry, videopoetry, and so on. By carrying this proposal out, this paper intends to offer some thoughts about a kind of poetry that has been shaping its own features along some decades of existence.

Within a perspective that relates poetry, image and sound in the digital-electronic environment, a small sample of digital poetry will be briefly analyzed, in order to set its constituents: the micro-computer (hardware and software); digitality; infographic image; poeticity and/or (il)legible word; pluri-signification of the poetry-image relation; the conscious use of poetics by the computer-operator-poet; intertextuality and hypertextuality; hypermedia resources; a possible similarity to the poet’s creation process; the use of verbal-vocal-visual-electronic-digital language in its poetic function, etc.

KEY WORDS

Genre Theory - Art and Technology - Cyberculture - Digital Literature - Digital Poetry - Digital Poetry Genre

SOME HELPFUL CONCEPTS

Ladislao Pablo Györi (Argentina) - VP 12

RALPH COHEN – I have emphasized the constituents of the text as a genre, the combinatorial parts that together produce effects upon readers. But it is necessary, also, to stress the notion of an entity, of the consequences of particular kinds of combinations, mixtures, multiple discourses, and intertextuality. The language that critics - modern and postmodern - use in discussing texts implies images of the human body as a system, as a biological organism (gender), as a machine. They refer to voice, to sight, to hearing, to smell, moving, etc. Overtly or implicitly the image of the body of the reader (sometimes of the narrator) is present in the transaction with a text. In drama, of course, the actor's body is a constituent of the drama whereas in postmodern fiction the body can be a theme as it is in Sukenick's "The Death of the Novel". But there is another sense in which the image of the text as a member of a genre is appropriate. Just as a human body has physically descriptive limits, so, too, does any text. The body is dependent on oxygen, on drawing into itself and excreting from itself substances that make it possible to endure as a physical entity, so texts depend upon the language of generic forms in order to be considered as verbal entities (COHEN, 1989, p.20-21).

E. M. de Melo e Castro (Portugal) - (C)ASA/HOUSE (11)

<www.ociocriativo.com.br/meloecastro>

EDMOND COUCHOT – The image is, from this point on, reduced to a mosaic of perfectly ordered points, a board of numbers, a matrix. Each pixel is a miniscule exchanger between image and number, which allows shifting from the image to the number and vice-versa. At the same time, the pixel launched numerical figuring techniques in a logic which was in total rupture with the figurative logic that underlies the image generated until then by the optical proceedings (optical-chemical and optical-electronic) (COUCHOT, 1993, p. 38-39).

JACQUE DONGUY – With the generalization of the computer resources that have conditioned us to perform a spatial circulation rather than only a temporal one around the text, the literary and poetic creation problem is put along with the new media, such as the computer, waiting for the production to be put in cd-rom format, and in other future numerical supports, integrating sound, image and text, fulfilling Raul Haussmann's dream, dating from the beginning of the 20th century, of a verbal-vocal-visual art (DONGUY, 1997, p. 257).

Cohen, Couchot and Donguy are three authors who treat new poetry in different ways. Cohen searches for the constituents of the text as a genre in order to understand the postmodern literature. Couchot approaches the digital image formation, and Donguy reflects upon the poetic creation on computer.

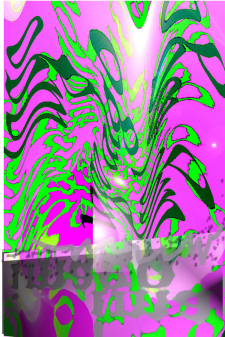

J. L. Antonio - Logo, logos, lago, algo (1)

The image above is a dialogue with Cohen's, Couchot's and Donguy's texts. At first sight, it is an image built with words, but it is also constructed by numbers, pixels, matrix, programming. It can be called infopoetry (2) or digital poetry and it could be the first reflection about digital poetry as a genre of several existing poetries (verbal, sound, visual, etc).

Paraphrasing Cohen's statements: what are the constituents of the digital poetry above? What effects do the combinatorial parts produce upon readers? What are the particular kinds of combinations, mixtures, multiple discourses, intertextuality that emphasize the notion of entity, that is, the entity of a digital poetry?

Colors, form, light, indication of movement, word traces. A vague similarity with a plant, perhaps by the choice of green "leaves" against a lilac background. We could ask: does knowing that these green "leaves" are processed computer images and that the words are logo, logos, lago and algo, help to produce the meaning that image can suggest to the reader?

INTRODUCTION

We can now affirm that part of poetry that is in books, magazines and newspapers, from many countries, has moved to the floppy disk, cd-rom, computer hard disk or to the site URL. In spite of this, many books, magazines and newspapers go on publishing verbal, visual and sound poetries which are simply circulating also in the new digital-electronic media, without, in many cases, assimilating what the new media provide.

There is no doubt that poetry still go on existing, and that poetry has adapted to the new media, but always maintaining the origin, the root, in other words, something that reminds verbal, visual, or sound existing poetries. It is also true that there is an innovative poetry that circulates on digital-electronic media.

Many denominations for this kind of poetry reflect concepts that demonstrate an effort to set boundaries for this kind of poetic communication. Because it is a world phenomenon, these terms are sometimes translated in each country’s language, but most of them are in English.

Many scholars seek to delimitate this new poetry and, in a certain way, differentiate it from other arts and literature. There are general denominations that remain as concepts which cover different forms throughout time such as experimental poetry, new visual poetry, new media poetry, or digital poetry. In most cases the expression visual poetry appears, without distinguishing it from a historical perspective or according to the use of different supports (paper, canvas, wood, etc.).

Our aim here is hence to map the existing digital poetry and, to a certain extent, configure it as one of the digital media discourse genres, stemming from the genre idea as a combinatory of elements. There is certain risk in using the term genre, because it reminds us of Aristotle, poetry, prose and drama, and so on. It appears to be a preset classification. But in this present study nothing is ready, everything changes as we access a different site, as we present or listen to a new presentation in a congress, festival, encounters, in an egroup’s discussion, and so on. A work in progress, or even a work in process. Something that happened, that happens, that will happen, that is happening, that has happened, that has been happening. The creations are coming out on digital media, the reflections about them are generating essays, and all of them are forming a theory and practice collection that forms a hypertextual, interactive and multi-faceted whole, typical to knowledge itself, not only the digital one.

Mapping the digital poetry as the continuation of oral poetry, which was declaimed supported by old musical instruments as the lyre and the flute in Classical Antiquity, is to establish an abstract route moving from its spoken to its written form. The poetry which was originally accompanied by musical instruments (Medieval Troubadourism) was followed by poetry without music (Humanism and Renascence), which, when read, rescued the orality and musicality of its previous forms, and evoked images through the singular syntactic constructions that produced rhyme, metrics, comparison, metaphors and metonymies, among other things.

The constant need for searching new languages in order to express the art that comes from the existence of new technology, from the use of interacting languages (I. A. Machado's concept (3)), the continuous relationship between art and science, and the new media utilization as a means of poetic expression: these seem to be the first elements we can identify as we look for new artistic communication media, among which we find poetic communication, that is, digital poetry. Like the character from "Asas" (Wings), by Mario de Sá-Carneiro (4), or the bizarre American woman and her five senses’ party in "A Confissão de Lúcio" (Lúcio's confessions) (5), another type of communication comes up closely to Andrews' electric word and his langu(im)age concept - <www.vispo.com> -, a product in/of/from the cyberspace. As it is a recent search, there is not only a single digital poetry, but many forms of it which express the various endeavors of fusion / interaction / dialogue among languages.

We can paraphrase Lavoisier's law, slightly modified: in the poetry’s world, everything which is created remains transformed, adapted. Today's poetry brings in itself yesterday's essentiality, absorbs what is contemporary as a form of expression and turns these resources into a powerful ally to stay alive and to expand itself on the new media, keeping itself at once entire and adapted.

That is the way the history of poetry seems to have been for us: the declaimed poetry, with all its mnemonic resources of rhyme, rhythms and metrics, survived in people's memory and was registered in books. Yet, it always was remembered and revered as the sound and word art. Poetry stopped being accompanied by musical instruments, as it was the case in medieval troubadour poetry, to become printed. It took several forms, became spatial, shaped itself in plastic forms like the visual ones, incorporated images, and survived, always, as poetry.

And today, with the arrival of the computer and the revolution it brought to our lives, poetry has remained as the art of the word in digital-electronic media. Like the books, which changed from printed to electronic, the printed poetry also became electronic. And it will remain, in a certain way, indivisible, differentiated, precise in its contours, even when it is adapted to other emergent media.

In short, the hypotheses that guide this paper are the following: the digital artistic texts differ from other texts (verbal, visual, audiovisual etc) in that they use the computer as a mediator between man and the sign production with esthetic aims. One of the most fascinating aspects of this study is that digital poetry is not limited only by the use of the computer as a support, for it comes in paper, video, movie, holography, performance, and so on. The media are large and reach many fields of knowledge. We can notice poetry in television programs, in video demonstrations, almost all of it made through digital proceedings. We can choose the best way to select and combine the medium we would like to work with (TODOROV apud CHANDLER, [s.d.]).

In a general sense, the digital artistic texts are seen from two viewpoints: the digital arts or the digital poetics, with the predominance of infographic images, holding a certain similarity with visual arts, and the digital poetry, as the union of poem, moving image and sound in the digital-electronic environment, by means of interactivity, hypertextuality, hypermedia and interface.

As this paper aims at mapping several digital poetries from many countries in order to classify them as genres of other existing poetries, we define digital poetry as the several creative and artistic products which use the word, the sound and the image bearing the poetic function. These products use the features stored in internal and external hard disks, floppy disks, cd-roms, videos, cassettes, and internet sites.

THE CONSTITUENTS OF DIGITAL POETRY AS A GENRE

To speak about genre implies knowing the word’s etymology and some leading concepts. The word genre comes from French (and originally Latin) and means 'kind' or 'class'. The term is widely used in rhetoric, literary theory, media theory, and more recently in linguistics, to refer to a distinctive type of text (CHANDLER, [s.d.]).

One of Fishelov's concepts comes in to help us achieve our proposed aim: genre is a

combination of prototypical, representative members, and a flexible set of constitutive rules that apply to some levels of literary texts, to some individual writers, usually to more than one literary period, and to more than one language and culture (FISHELOV, 1993, p. 8).

If we extend the concept of a flexible set of constitutive rules that applies to some levels of literary texts, we can includeamong the latter the digital texts. We can also add Todorov's statement that "a new genre is always the transformation of one or several old genres" (TODOROV, 1980, p. 46).

Fishelov builds up the concept of genre from four analogies: the biological analogy, the family analogy, the institutional analogy and the speech-act analogy (FISHELOV, 1993, p. 1-2). Adena Rosmarin states that a genre is

a kind of schema, a way of discussing a literary text so that it links with other texts consecutively and, finally, comes to express this process in terms that link it with other texts, and finally, phrase it in terms of those text.... We can always choose, correct, invent, or define a class wide enough to make the desired mistake possible (ROSMARIN apud FISHELOV, 1993, p. 11).

Taking Ralph Cohen's concept of genre, we have the four theoretical bases to help us in the establishment of the constituents of the digital artistic text as a genre, which is our first reflection before we come to the digital poetry genre.

Combination of prototypical and representative components, a flexible set of constitutive rules, a kind of schema, combinatorial parts that together produce effects upon readers, particular kinds of combinations, mixtures, multiple discourses, intertextuality - this set of expressions works and becomes the basic elements for the aim of this paper, in the search for the constitutive elements of the digital poetry as a genre.

A survey of different kinds of digital poetry led us to map its constituents, for this procedure proved to be the most adequate one to verify the combinatorial parts that together produce effects upon readers-operators, and it also helped to find out their "physical" limits, that is, the particular kinds of combinations, the intertextuality, the hypertextuality, the interface, etc., finally, the "intermediality, the "inter-relationship among different media, such as image / sound / movement and text mutually entangled, which is what the computer allows" (LAJOLO, 1998, p. 70; idem, 2005, p.34).

In a general sense we can thrive on Uspensky's concept of artistic text from this point onwards. From the idea of digital-electronic artistic text, whose support is electricity and whose instrument of reception is the computer screen, we can think of many different utilizations of electronic-digital media as a form of artistic communication, in general, so that we can come to the notion of digital poetry (the particular use of word and infographic image with a poetic function). This text aligns with the cyberculture art: the participation of those who experience it, interpret it, explore it or read it, that is, the typical organization of collective and collaborative processes, etc. (LEVY, 1997, p. 94-95).

Digital poetry belongs to the mediatic genres, that is, it is produced by one of the mediatic communication means: the computer and its technical language. It is important to point out that digital poetry is not only limited by the computer as a support, for it can come in paper, video, holography, performance, and so on, for the media are varied and reach many fields of knowledge. The technical language of the computer underlies or is previous to what is presented as the final product, that is, the work of art (literary, plastic, visual, photographic, cinematographical, theatrical, digital, etc.), but this product is shaped, configured, determined, and conditioned by the language that organizes and makes the computer work (6). For instance, the producer-operator-digital artist (9) knows the rules to operate some software, but he might not know the machine and its components rules (hardware). Once he knows the software rules, he/she tries to adequate, configure and shape his/her modus operandi to the computer’s one, for only this way will the digital artist-operator be able to express himself/herself through the machine. If he/she is acquainted with the hardware and can interfere, then he/she will produce other creations, thanks to the possibility of using programming as a creative and artistic process.

The basic condition to establish the digital poetry genre is the presence of the word associated to the digital image in an analogical way. The presence of word indicates a relationship of the word with poetry, the art of the word, in everything poetry’s legacy has brought of beauty, sound, feeling, and even of cryptic aspects. Therefore, it is not only the presence of the word, taken as letter, linguistic or poetic sign, but something that produces poetry sensations.

The language that digital poetry presents (sound + verbal + visual + electronic + digital) is predominantly used in its poetic function, in the same way this concept is presented, exemplified and developed by Jakobson, that is, it has similar proceedings to poetic work, by means of the union between the poem (8) and the digital image.

The alternated predominance of word and/or image and/or technology has been the unchaining element of various digital creations and, in a certain way, it allows us to classify them as digital poetry. It is important to emphasize that the inclusion of sound is an integrating part of the process.

This is the first delimitation or frontier for us to come to a definition of artistic digital texts, in a general sense, so that we can arrive at digital poetry: a certain number of verses that "suffered" the computer action, or a poetic message elaborated from constituents of a computer taken as a whole. Hence, in broad terms, the constituents of the artistic digital texts are: the existence of a computer (hardware and software); the digitality; the presence of infographic images; the existence of a kind of poeticity, with or without the presence of the word; the sound associated to the word or the music, integrated to the whole set; the plural signification of the infographic image, associated or not to the word; the digital text as an object to be contemplated or with which is possible to interact (interfaces), including the possibility of modifying it; the constant use of intertextuality, hypertextuality; the register in magnetic means like video-cassettes, cassette-tapes, floppy, zip or hard disks, cd-rom, or even in paper, partially or totally.

As a way to consider the constituents of artistic digital text as a genre, we can state that the creative processes are the fundamental features to be taken in to make the following classification possible: digital poetics, with the predominance of infographic images; digital or virtual narratives, which use the digital-electronic resources and interfaces to develop a non-linear narrative; and finally, the digital poetries, which establish a relationship with poeticity, sounds which are similar to music or oral poetry, or the representation of a sound mass by means of letters or words, legible or illegible words, and infographic image with poetic effects.

Although apparently obvious, the operator-poet's formation can be a decisive aspect for the poetry, narrative or digital poetry, or the pragmatic use of electronic-digital processes. It is necessary to start from a certain point of view: this particular way of seeing belongs to the artist, the writer or the poet. It is also important to emphasize that it is the esthetic look at the technological product that gives it a poetic function, over a referential or pragmatic treatment.

In a general sense, these considerations lead us to present some particular features of the digital poetry. The use of a computer, even when we are working with a sonnet, for example, implies the mediation of text and/or image editor, which alters the final product. This poetry is limited and shaped by the technical language that is part of the computer (9). Each reader-operator will see and read this poetry in the way his/her computer allows, according to the choices and limits of the machine he/she has and according the reader-operator's technical knowledge. The access to this poetry is made through a machine (which is a totally different attitude from opening a book, a magazine, a newspaper, copybook): turning on the computer and reading on the monitor screen, turning on a video, listening to a cassette, a cd-rom, and so forth. It is a representation of what has been done and also a re-making by a microcomputer.

Digital poetry allows, if so were the programmer's wishes, the reproduction ad infinitum on the monitor or in the paper, in the way the machine can reproduce, in the way the admirer -operator is able to access, according to the technical resources of his/her software and hardware, that is, according to the different ways that his/her machine is able to reproduce the poem.

Each reader-onlooker-admirer-operator can select this digital poetry in his/her own way, clipping or not, reproducing or not the text his/her the way he/she wants, in his/her printer, with the technical resources he/she has at his/her disposal, in short, in the way the reader can access it.

Digital poetry is hypertextual and intertextual, for it talks to itself, to the word or to the trace of it, to the image, to the "external world", to the "internal world" (of the machine, hardware, software, etc.), to the sound that the word evokes, or to the sound included in this set, to the reader-admirer-operator, and to the machine operator. An artistic digital text, and also the digital poetry, makes part of and participates in other cultural texts, and talks to the culture, receiving various influences. Therefore, by naming this text digital poetry, we attribute to it the general characteristic of poetry, that is, language as well, though not only verbal (for it talks to plastic, visual, sound, theatrical, photographic, videographic and holographic arts, etc.), that behaves similarly to poetry. Similar to poetry means that a poet-operator (now it is not the poet who writes, but the one who hits the keyboard and operates a machine) makes use of procedures that have similarity with the verbal poetic process-making.

If we have the elements word, image, and the relationship between them, the word or its vestige leads us to the sound, actual or imagined. For example, the printed verbal and/or visual poetry, when read, out loud or not, makes us assume sonority or musicality. At this point there seems to be an interweaving among poetic genres (those from voice), the literary genres (those from littera, that is, word) and the media genres.

The interfaces (mouse, keyboard, monitor, software and hardware) working simultaneously as man's extensions and as the interchange between man and machine, as once did pen and pencil and/or the typewriter, represent the process of feeling with, of feeling and expressing ourselves through, of mediating and replacing the hands and their "imperfections" by processes which are supposedly (or apparently) "perfect" for creative and artistic productions. These interfaces enable a search for a more direct reading between poetry and man, by means of the computer intermediateness. It is an attempt of "humanizing" the technology (10).

The reading of this digital poetry is made in various different directions, combinations, crossings and intersections: on the paper (letter, single page, newspaper, magazine, review, etc.); on the computer; on the screen, in three-dimension, in movement or not, in a linear form in the graphic-spatial representation - a verse after other; in a hypertextual form, that is, parts of the poems that lead us to other links, verses, poems, words, quotations, etc., in a non-sequential way, which is maze-like and individual. In other words, the entrance for the poetic text is made in a different way each time we read it.

The fourth dimension, the virtual one, differs and is "opposite" to the dimension of the printed digital poetry, a static and reduced result from what we see on the computer screen. This virtual dimension enables operator-reader-onlooker-admirer's new readings.

The simulation of an element of reality is an attempt to pass something off as being reality itself, what the admirer starts feeling, instead of imagining. How much of simulation is there in digital poetry? Does it intend to pass itself off as poetry, modified, shaped, suitable for the digital media? In a slow process, since the computer poem by Théo Lutz came to be known, in 1959 in Germany, until the most recent internet poetry, a new poetry has been under shaping with a specific and particular discourse, which represents a new way for the poetry.

Despite not being its exclusive attribute, the notion of overlap writing, the palimpsest, has also become a current way of the digital poetry production, since it is one of the integrating parts of the variation process, for, in many times, verbal poetry is a palimpsest of other (il)legible experiences. In the same way, visual poetry is also a palimpsest of other (il)legible visual syntaxes. On the digital-electronic medium, the fusion of verbal and visual poetries determines an initially double palimpsest, though it comes with the richness provided by digitality. It is the overlapping of poetry (verbal, visual, sound, electronic, digital, etc.), that is, words and images, "the most possibly heterogeneous and incongruent, wanting to challenge, to the limit, the metonymical process of interpretation" (CAUDURO, 2000).

The inclusion of mathematical symbols (Melo e Castro, Vallias, Steve Duffy, etc.), the presence of emoticons, formulas, diagrams, computational program languages like HTML, all of them indicate another approach for art and science, art and technology, or poetry and science, and technology, as we can notice with the route to hypertext in Rosenberg's diagram-poems - <http://well.com/user/jer/diags4/d4.1.html>, Vallias' - <http://www.refazenda.com.br/aleer/> - or Györi's - <http://lpgyori.50g.com/0_digital_works/poesia_htm/vpoems2_htm/07_vp2.htm. -.

We can also borrow what Abraham Moles defines as creating machine myth, and apply this concept in order to claim, for example, that an image editor like Adobe Photoshop, as well as any other programmatic resource or software, is a creating machine, which depends on the operator-poet's technical, esthetic and poetic knowledge, creativity and skill to produce digital poetry. At random or intentionally, the poet-operator inscribes his creation in the electronic digital media.

THE DIFFERENT DIGITAL POETRIES

Jim Andrews - ABCArchitecture

<http://www.vispo.com/E/ABCArchitecture.html>

There is a significant variety of poetries which circulate in the digital-electronic media (internal or external hard disks, floppy disks, CD-ROMs, videos, microcomputers, internet). Without having the aim to exhaust the subject, neither to trace a historic route, this is a mapping of the several kinds of digital poetry.

1 - There is a verbal poetry, which circulated in books, magazines and newspapers, and is now using the cyberspace. It is a transposition of media, not only an updating, a fad or an optimization of another space: it means a poet's attitude, and also a reader's one, in relation to the modifications this exchange imposes. It is not only the changing of the media as a way to reach more readers, but also the shaping of the graphic spatial disposition of this poetry by computational rules. It is the poetry which was digitalized in a microcomputer, with the use of text and/or image editor, which now is part of a "digital" literature, that is, it occupies the virtual medium. If it can be seen only as a historical aspect - the first poems collected in electronic anthologies -, it is necessary to emphasize that the contact with this kind of poetry is the relationship between man and machine, which results in another form of reading, even though this poetry doesn't present innovative elements, even though it is nothing but a printed poetry that now occupies the cyberspace, as a kind of reproduction of the print environment.

2 - There is a sound poetry, which was transmitted orally as art of spoken word, which has also become digital, mainly by the use of electric-electronic-digital resources, like the sound laboratories. This poetry, which was a great development during the historic vanguards (Futurism, Dadaism, Cubism, etc.), is created by means of sounds which are separated, in a certain way, from the meaning (the phonemes don't form a word) and it represents a kind of digital poetry, usually named sound poetry. In some cases, it is separated from sound and digital, because the sound poetry is to be heard only, as Philadelpho Menezes's concept of sound poetry (MENEZES, 1996 e 1998). In other situations, especially in several sites (Jim Andrews, Komninos Zervos, etc.), sound poetry is a part of other languages, a kind of interacting languages (verbal, visual, sound, electronic, digital poetries).

3 - All types of visual poetry is spontaneously and naturally adapted in the computational medium. It is an adaptation of supports, like Arnaldo Antunes' - <www.arnaldoantunes.com.br> -, Elson Fróe's - <http://www.elsonfroes.com.br/visual.htm>

-, Melo e Castro's - <www.ociocriativo.com.br/meloecastro> - sites, among others. Considering its graphic and spatial characteristics, the same occurs with the concrete poem, as Augusto de Campos says: "Since I, in the 90’s, could put a hand on a personal microcomputer, I noticed that the poetic practices in which I am involved, emphasizing the materiality of words and their interrelationship with the non-verbal signs, have a lot to do with computer programs. The first animations came out from graphic and sound virtuality of the pre-existing poems" (A. CAMPOS, 1999).

We can affirm that the Brazilian concrete poetry, the Portuguese experimental poetry, as well as the later visual poetry, which are going to be "updated" on the new medium, can be called as the precursors of digital poetry.

There is no doubt that visual poetry has its own characteristics which differ a lot from digital poetry in various aspects such as support material, paper, the handicraft that drawing uses, colors and materials from the plastic arts, the use of the three dimensions limit, certain own individuality of the handicraft, and so on. For Capparelli et al the difference is: "Visual poem and cyberpoem have an indetermination of content present in the object and/or attributed by the reader. In the visual poem both are imbricated, despite the higher or lower reader's ability to notice the links; however, they are finite by the very nature of the object. Differently from the visual poem, the cyberpoem demands a skillful and attentive reader, someone who has technical abilities. Through the interactivity the reader becomes the work's co-author. The old-fashioned idea of authorship is challenged. In the visual poem, the authorship can be shared." (CAPPARELLI; GRUSZYNSKI; KMOHAN, 2000).

4 - The concept of writing machine, borrowed from linguistics and developed by the Bense's and Moles' informational esthetics, is going to incorporate the use of machine as the possibility of "creating artificial texts with meaning" (MOLES, 1990, p. 149): "The writing of a text using a machine, be it real, a great computer, be it "imaginary", that is, constituted of a series of operations to be made or to be ordered by operators without intelligence - is finally the synonym of intellectual creation".

It is experimental literature: "It comes from a very general definition of language - it is a system of signs and symbols brought together according to certain rules - and proposes a new idea of literary message, distinguishing in the analysis the content and the continent, the semantic aspect and the esthetic one" (idem. p.150).

This is the concept of poster attributes constellation (MOLES, 1990, p. 158), proposed by Moles: "It is a graphic crystallization of laws of association that the spirit follows in joining a central sign (inducting word) with a series of other signs (inducted word)" (idem, p. 151). In our opinion, the hypertext principle seems to lie here: the spatial relation of the word, as in the diagram-poem Diagram 4.1 by Jim Rosenberg, the virtual poem VP12 by Ladislao Pablo Györi or the hypermedia poetry Antologia Laboríntica by André Vallias.

5 - The text below shows one of the first uses of computational technology as a form of artistic and literary expression, the permutational poetry, in which a storage of word is treated by the resources of a machine, and then produces similar texts, based on a computer program. Moles and Barbosa studied exhaustively the subject and published several theoretical studies and anthologies. This is an example taken from the Italian Nanni Balestrini in early 60's:

MENTRE LA MOLTITUDE DELE COSE ACCADE I

CAPELLI TRA LE LABBRA ESSE TORNANO TUTTE E ALLA LLORO

RADICE L ACCECANTE GLOBO DI FUOCO GIACQUERO

IMMOBILI SENZA PARLARE TRENTA VOLTE PIU LUMUNINOSO

DEL SOLE FINCHE NON MOSSE LE DITA LENTAMENTE SI

ESPANDE RAPIDAMENTE CERCANDO DI AFFERRARE LE

SOMMITA DELLA NUVOLA

MENTRE LA MOLTITUDINE DELLE COSE ACCADE L ACCECANTE

GLOBO DI FUOCO ESSE TORNANO TUTTE ALLA LORO

RADICE SI ESPANDE RAPIDAMENTE FINCHE NON MOSSE LE

DITA LENTAMENTE E QUANDO RAGGIUNGE LA STRATOSFERA

GIACQUERO IMMOBILI SENZA PARLARE TRENTA VOLTE PIU

LUMINOSO DEL SOLE CERCANDO DI AFERRARE ASSUME LA

BEN NOTA FORMA DI FUNGO (BALESTRINI, [s.d.], [s.da], [2004])

6 - Other endeavors to analyze and map different digital poetries have been made by scholars like Funkhouser, Barbosa, Moles, Bense, I. A. Machado, Tolva, Parente, Vallias, Capparelli, Andrews, etc. Poets like Nanni Balestrini, André Vallias, Melo e Castro, Augusto de Campos, Cláudio Daniel, Ladislao Pablo Györi, Jim Andrews, Ted Warnell, etc., who have been devoted to the relationship between art and technology, have established denominations and differentiations for their poetic experiences with the computer. Moreover, we have had individual (certain poet-operators) and collective (particular ways of producing digital poetry) constitutive elements.

Printed and electronic magazines and newspapers (in floppy disk, cd-roms, cassette tapes, video cassettes, internet) have presented many essays about the subject.

Many issues of Dimensão: Revista Internacional de Poesia (12) present opinions of theorists and digital poets. In the 1995 issue, Cláudio Daniel (Brazil) discussed the relationship between poetry and computer as a form of differentiated poetic expression, and Ladislao Pablo Györi (Argentina) introduced some criteria for a virtual poetry which uses the third dimension and is made in virtual space. In the 1998 issue, E. M. de Melo e Castro (Portugal and Brazil) presented a kind of theoretical-practical manifesto which developed the concept of 3D transpoetic, with a series of 13 infopoems, synthesized in 1997 and 1998 in a PC, in Windows 95 environment, using the softwares Adobe Photoshop 4.0, Fractint V18 and Corel Motion 3D 6. In the 1999 issue, Melo e Castro and his students presented many comments about this kind of digital poetry (13).

The newspaper Folha de S. Paulo,in its section called "Folha Informática", introduced many and different experiences related to digitality under the generic denomination of digital poetry, without establishing any difference regarding verbal, visual, sound, electronic or digital poetries. Some authors, theoreticians, and also study centers, are cited: Eduardo Kac - <http://www.ekac.org> -, Ted Warnell - <http://warnell.com> -, Electronic Poetry Center (USA) - http://writing.upenn.edu/epc/e-poetry -, Janam Platt, Loss Pequeño Glazier, Mark Napier, Mark America, among others. Besides introducing some sites of digital poetry, the newspaper presents some studies and sites about digital literary theory, by Allien Flower, Augusto de Campos, Cyber Poetry Gallery, Komninos Zervos, George Landow, Hypermedia Research Center, Jim Rosenberg, Parallel Notion, Christopher Funkhouser, John Cayley, etc. The articles printed on that newspaper try to delimitate the concept of digital poetry, including an interview with Augusto de Campos and Mark Amerika. As a first study, trying to be general and to reach all fields of knowledge, though not deeply, the material should be better developed in a further edition.

7 - Funkhouser refers to a "poetry created by writers (and programmers/producers) who rely on the computer to bring their visions to the world through the effusive light and linkage of the screen" (FUNKHOUSER, 1996). For him, "all poetry which uses a computer screen as hypertextual interface falls into at least one of the following five categories" (ibidem):

Hypermedia - "includes graphics, moving visual images, and soundfiles linked with (or instead of) printed text; a variety of intertextual associations and graphical combinations are possible" (ibidem).

Hypercard: Alphabetic and visual texts are arranged in a series of digital filecards and linked to each other; some files include sound; the supercard enables the use of video (ibidem).

Hypertext: Historically, written text only, with links to other writing; some titles include static visual images; gradually evolving (ibidem).

Network hypermedia - Predominantly exists on the World Wide Web (WWW); currently without synchronous sound and video capabilities (ibidem).

Tex-generating software - Programs which automatically arrange words and images (ibidem).

8 - Focusing different cyberpoetries based in technologies, Capparelli, Gruszynski and Kmohan (2000) have come to the following classification:

galleries and collections net - texts blocks or galleries, more specifically visual poems;

poems factory - computer programs which generate text;

sound poetry - some sound poetry sites which recapture experiences from Marinetti's Futurism and Hugo Ball's Dadaism;

declaimed poetry - sites in which, for example, an actor or the poet him/herself reads out his/her poems;

new visual poetry - experiences which go beyond the traditional visuality, producing 3D visual poems;

kinetic poetry - poetic genre in which animations are created in poetry by means of various techniques;

9 - Among some study centers spread around the world, the Estúdio de Poesia Experimental (Studio of Experimental Poetry) - <http://www.pucsp.br/~cos-puc/epe/index.html> -, site from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, Brazil, which was coordinated by professor Philadelpho Menezes (1960-2000) - http://writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/menezes/ -, presents many verbal, visual and sound poems that configure an on-line poetry anthology, with poems by Katalin Ladik (Yugoslavia), Eugen Gomriger (Switzerland), Ana Hatherly (Portugal), among others. This site makes links with other poets from many countries, making the EPE an online digital poetry world’s anthology.

10 - Although classified as digital poetics by Plaza and Tavares, we can refer to Ricardo Araújo's experiences with Augusto de Campos, Haroldo de Campos, Décio Pignatari, Arnaldo Antunes and Júlio Plaza's poems, which are transformed into videopoetry and analyzed in the book Poesia Visual e Vídeo Poesia (1999).

11 - At the Communication and Semiotics Program at the Pontifical University of São Paulo, Brazil, a site called Interlab - Intersemiotics Studies on Hypermedia and Labyrinth (28) presents some digital arts by four digital artists, among them, for our study, the important contribution is Sílvia Laurentiz's recreation of the poem "O Eco e o Icon" (1994), by E. M. de Melo e Castro, in 3D visual and sound interactive environment, produced in VRML2, in 1997.

12 - There is a "group of experiences which represents the convergence between verbal language, image (static or dynamic), and audio in poetry (CAPPARELLI, 2000). It is the hypertext poetry which presents "like a number matrix in files and columns in the memory of a computer. Numbers and pixels can be changed and manipulated, individually or in groups, and the set can be translated into images on a TV monitor or, even, in a printed form. Any change in the numbers matrix implies a change in image." (PLAZA; TAVARES, 1998, p. 73).

13 - The interpoetry, that is, the hypermedia interactive poetry, created by Philaldelpho Menezes and Wilton Azevedo, is another contribution to the digital poetry:

Interpoetryhas two meanings: interaction and inter-signal poetry. The name, inter-signal poetry, summarizes the idea of poetry that uses verbal and non-verbal signs. In the second semester of 1997 we started to produce poems in which sounds, images and words are mixed, a complex inter-signal process, in a technological environment that favors the presence of verbal, visual and sound signs, together with hypermedia programs (MENEZES; AZEVEDO, 1999/2000, p. 98).

Philadelpho Menezes e Wilton Azevedo (Brazil) - Interpoesia

14 - Leading the creative use of the electronic media to the specific objectives, creating a relationship between word and image by means of image editor: this is one of the many Melo e Castro and his Brazilian and Portuguese students' experiences. In his route through verbal, visual, concrete and digital poetry, Melo e Castro uses many denominations for the digital poetry he creates. Infopoetry has the first meaning of permutational poetry as he presented in Álea e Vazio (Aleatory and Emptiness), poetry book of 1971, especially with the poem "Tudo pode ser dito num poema (Everything can be said in a poem)" (CASTRO, 1990, p. 225-226). Videopoetry will be a concept, and in this field he is a pioneer in Portugal, which presents the first relationship between poetry and video, in Roda Lume, 1968-1969, Signagens, 1985-1989, and Sonhos de Geometria, 1993. Besides being a poet, Melo e Castro is also dedicated to essay writing. Among his several critical and theoretical works, he is the author of Poética dos Meios e Arte High Tech (Media Poetics and High Tech Art) (1988) (32), in which he discusses the media poetics (the intersemiotic net between oral and visual, the photographic vision, movie, and mail art) and high tech art (infoart, infopoetry, videopoetry, holopoetry, fractal esthetics, zero gravity poetics, dematerialization, teleart, robotics, etc.). The same infopoetry becomes another concept, that is, the poetry treatment related to an image, which was called in his first experiences "Infopoesia / Videopoesia: 1985-1993" (Infopoetry / Videopoetry), and they are brought together in Visão Visual (Visual Vision) (1994). In Finitos mais Finitos (Finites plus Finites) (1996), the poet registers two experiences of 1995: the first, named infopoetry, resulted from a working paper in Yale Simphosophia on Experimental, Visual and Concretic Poetry in 1995, in Yale University, USA. This is already an experimentation that associates word and image in a microcomputer, by means of Adobe Photoshop. The second, called Cibervisuais (Cybervisuals), was part of the exhibition "Poesia Visiva e Dintorni" (Visual Poetry and Similar Ones), in Spoleto Museum, in Perugia, Italy, also in 1995. During 1997, Melo e Castro was an invited professor at Communication and Semiotics Program at PUC SP and he conducted two courses: one on Infopoetry and Sound Poetry, and another on Infopoetry in 3D. From these courses, he created two other concepts: the 3D transpoetics, which represents his individual and students' poetic experiences with Adobe Photoshop 4.0, Fractint V.18 and Corel Motion 3D 6; and pixel poetics, which resulted in Algorritmos (1998) (14).

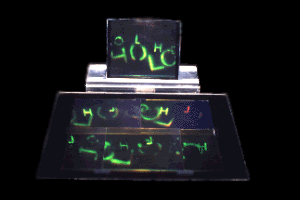

15 - Holopoetry and the new media poetry by Eduardo Kac - <http://www.ekac.org/holopoetry.html> -, using interactive work, transgenic art, telepresence art, and so on, are one of the most important digital poetics.

Holopoetry is

organized non-linearly in an immaterial three-dimensional space and that even as the reader or viewer reads the poem in space - that is, moves relative to the hologram - he or seh constantly modifies the text. A holopoem is a spatio-temporal event: it evokes thought processes and not their result (KAC, 1996, p. 186).

Eduardo Kac (Brazil/EUA) - Holo-olho

<http://www.ekac.org/holopoetry.html>

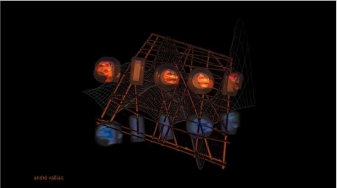

16 - André Vallias is a graphic designer who works with multimedia, visual poetry and electronic art. He had exhibitions in Germany, Vienna and Tokyo. His digital poetry includes word and images in an interactive action: each letter or fragment of image allows access to different parts of his "Antilogia laboríntica [poema em expansão]" (15) - <http://www.refazenda.com.br/aleer/> - . There is a fusion of the present poetry, and many times it is written, with or without cuts, and the set combines high-quality webdesign with an excellent visual effect.

André Vallias (Brazil) - Antilogia Laboríntica

<http://www.refazenda.com.br/aleer/>

17 - "Computers poem", or "electronic poetry" - <www.cce.ufsc.br/~nupill/poemas.html>-, by Gilberto Prado (from USP - Sao Paulo University, Brazil) and Alckmar Luiz dos Santos (from Federal University of Santa Catarina), is a kind of digital poetry which presents a relationship that links Brazilian verbal poetry, image and sound: a multimedia artist and a poet, both university professors, join their theoretical, practical and creative knowledge in a product that combines plastic arts and literature.

Without trying to exhaust the subject, which is in process and progress day by day, these are some of the possible different digital poetries we have searched up to present moment, which does not allow us to present a general panorama, like Funkhouser or Capparelli, but enables us to notice a delimitation: the denomination digital poetry refers to experiences that involve a fusion of poetry with digital image in their various forms.

VARIOUS NAMES FOR DIGITAL POETRY

What terminology can be given to the poetry that yields, goes beyond, superposes, interposes, passes by the word and "goes" to the computer? If the mapping of the constituents of digital poetry as a genre has been a constant problem, the denomination of these experiences has been another and difficult problem also. Our searches lead us to a various names that are sometimes based on experience, and sometimes based on the different ways of making digital poetry. The list below is the first result of our study: the title of the poetry, its brief description, and the authors who named it. We adopted the alphabetical order.

Autopoems– Theo Lutz, Germany, 1959 – poetic experiences with a computer that generates poetry, that is, verses, in a sequence of words and phrases by permutation, combination, associations of words. We have an example in English - <http://www.stuttgarter-schule.de/lutz_schule_en.htm> and in German - <http://www.stuttgarter-schule.de/lutz_schule.htm>.

Cine(E)Poetry- creative work of film and poetic video makers. The group involved in this experience called LTV (Literary Television), is from the USA, and was previously known as Film Workshop. They collected a very big file to be distributed to television, cable broadcaster, educational institutions, and internet webcasters. The Cine(E)Poetry makes experiments with visual image, using a video arrangement, film, animation, sound and computational techniques, and all these non-verbal languages share a special focus with spoken and written poetry as something essential as a whole. The term was coined by George Aguilar (USA): <www.george.aguilar.com>.

The term was coined by George Aguilar (USA): "Cin(E)-Poetry looks for the symbiotic relationship of the image, word and of the sound with the music. She uses the cinematic rhythms in the edition, in the same way that the time of the music and the content of the spoken word, to maintain the animation and the continuity. (...) Cin(E)-Poetry is an artistic form that it combines images, sounds, music with a written poem or spoken to create a work of art multimedia (AGUILAR, s.d.).

Computer poem- Théo Lutz (1959, Germany), Brion Gysin (UK/USA, 1960), Nanni Balestrini (1962, Italy).

Cyberpoetry - For Barbosa (1996), it is essentially permutational poetry, and for Capparelli (Brazil) (1996) - http://www.ciberpoesia.com.br/ -, it is a visual and interactive poetry adequate to the digital and electronic media; the term is also used by Komninos Zervos (Australia) - <http://live-wirez.gu.edu.au/Staff/Komninos/Cyber/masters95/masters.html>- and Brian Kim Stefans (USA) - <http://www.ubu.com/papers/ol/stefans.html>.

Cybervisual- named by E. M. de Melo e Castro for a series of infopoems which were presented in a collective exhibition in Italy.

Diagram-poem- non-linear experiences by Jim Rosenberg since 1966, with a series of multi-linear poems called "Word Nets", that, from 1968 on, evolved to the "Diagram Poems".

Digital Clip-poem- Augusto de Campos in his site (1997).

Digital poetry- newspaperFolha de S. Paulo(1999); term used since 1990, especially derived from digital poetics.

Electric word - although using word, instead of poetry, Jim Andrews presents some considerations about the use of the poetic word in a digital-electronic context. (Andrews 1997-1999).

Electronic poetry- generic name given to the poetic experiences on the computer (Funkhouser 1996).

Experimental poetry- name adopted by many countries, poets and poetic movements: the Portuguese Experimental Poetry (decades of 60's and 70's), a general Hispanic-Brazilian-American movement, according to Clement Padin, in a period from 1950 to 2000. In the International Poetry Festival of Medellin, in Colombia, in December 2000, it also designated: visual poetry, gesture poetry, poetic performances, poetic actions and interventions, videopoetry, virtual, digital or multimedia poetry, holopoetry, and sound poetry.

Galleries and net anthologies- textsblocks or galleries, more specifically visual poems (Capparelli et al 2000);

Holopoetry - denomination given by Eduardo Kac in 1983.

Hypermedia poetry- "includes graphics, moving visual images, and soundfiles linked with (or instead of) printed text; a variety of intertextual associations and graphical combinations are possible" (Funkhouser 1996: 1/7)

Hypercard: Alphabetic and visual texts are arranged on a series of digital filecards and linked to each other; some files include sound; the supercard enables the use of video (Funkhouser 1996: 1/7)

Hypertext: Historically, written text only, with links to other writing; some titles include static visual images; gradually evolving (Funkhouser 1996: 1/7).

Hipertextual poetry - George Landow (1995), use of non-linear model, applying hypertext.

Infopoetry - Melo e Castro, with two different meanings, one in Álea e Vazio (1971) and another, in the paper The Cryptic Eye at Yale University in 1995.

Internet poetry - poetry in WWW.

Interpoetry or hypermedia interactive poetry - Philadelpho Menezes and Wilton Azevedo (1997/1998).

Intersign poetry - Menezes (1999) in the Studio of Experimental Poetry at the Communication and Semiotics Program at PUC SP.

Kinetic poetry - poetic genre in which animations are created in poetry by means of various techniques (Capparelli et al 2000);

Net poetry - poetry in the WWW.

Network hypermedia - Predominantly exists on the World Wide Web (WWW); currently without synchronous sound and video capabilities (Funkhouser 1996:1/7).

New media poetry - term used by Eduardo Kac in an anthology of essays under the same title (1996) written by Jim Rosenberg, Philippe Bootz, E. M. de Melo e Castro, André Vallias, Ladislao Pablo Györi, Eduardo Kac, John Cayley and Eric Vos.

New visual poetry - experiences which go beyond the traditional visuality, producing 3D visual poems (Capparelli et al 2000);

Permutacional poem- Nanni Balestrini (1970, Italy), Silvestre Pestana (1981, Portugal) and others.

Pixel poetry or pixel poetics - Melo e Castro (1998).

Poem on computer - Gilberto Prado and Alckmar Luiz dos Santos (1995).

Poems factory- computer programs which generate text (Capparelli et al 2000);

Poetechnicor digital poetics - Plaza and Tavares (1998: 119) do not separate poetry from poetics, for they only denominate digital poetics the several ways of making infographic image. The word, for the authors, is the infographic image inserted in a bigger context, although it has meaning with the image, besides it, and/or independent of it.

Plaza and Tavares use Luigi Pareyson's concept of poetics (the various forms of poetics have operative and historical characteristics) and Umberto Eco's (poetics is an operational program initially proposed, or even better, it corresponds to the project of formation or attribution of a given work).

Sound poetry- some sound poetry sites which recapture experiences from Marinetti's Futurism and Hugo Ball's Dadaism (Capparelli et al 2000);

Text-generating software - Programs which automatically arrange words and images (Funkhouser 1996:1/7).

3D transpoetic- Melo e Castro (1998).

Videopoetry- although it refers to poetry made with video techniques (Melo e Castro, Arnaldo Antunes and Julio Plaza, for example), the expression can mean the video treatment to poems, as Ricardo Araújo did with some Brazilian poets.

Videotext - language media and distributor of information by means of a telephone as a means of transmission. Despite the use of the suffix text, it was used for poetic production (Plaza 1986).

Virtual poetry or vpoem - Ladislao Pablo Györi (1995).

Web poetry - poetry in WWW since 1990.

The list has not had the intention of covering the subject as a whole, but only intended to show many names which have been appearing as the digital poetry is being developed.

A KIND OF CONCLUSION

By decomposing the whole in parts, as we have done, does it allow us to delimitate a "form" of digital poetry? Is it a valid process?

The sample we have collected along this essay has shown us different routes which configure the digital poetry as one of the genres of the present poetries. Above all, it is possible to notice that the use of the poetic word as an unchaining element of the reading process that links word, image and sound in a digital-electronic context.

NOTES

(1) The Portuguese words Logo, logos, lago, algo have some sound and written similarity, but not in English: soon, Logos (the Divine Word), lake, something. By means of the resources of Adobe Photoshop an image came up from these words.

(2) Infopoetry is the name given by E. M. de Melo e Castro in a Course of Infopoetry and Sound Poetry in Postgraduate Program in Communication and Semiotics which was given to eleven students in the first semester 1997.

(3) The sensorium (sensorial aspects or senses in general)rediscovered: critical routes of interacting languages (I. A. MACHADO, 2000, p. 73-94). The essay talks about the relationship among music, poetry, fiction, image, video, and so on, with the aim of studying it from the literary criticism viewpoint.

(4) Mário de Sá-Carneiro (1890-1916) was a Portuguese poet and writer and Fernando Pessoa's friend, with whom he founded the magazine Orpheu, which started the Modernism movement in Portugal in 1915.

(5) This is another Mário de Sá-Carneiro's novel, published in 1914, whose main subject is the interacting languages in the beginning of 20th century.

(6) Examples: cyberpoetry, for Komninos Zervos, is a combination of concrete, sound and computer poetries; langu(im)age, according to Jim Andrews, is composed by visual, sound, verbal and electronic poetries; it is called visual poetry from cyberstream, by Ted Warnell, and it is a mixture of visual and verbal poetries with the use of computer and collaborative work and hypertextuality; and so on.

(7) The preference for producer-operator-digital artist seems more generic and suitable to the text than producer-operator-poet or producer-operator-writer.

(8) To the notion of poem we can extend the notion of word plus sound plus image in a digital-electronic environment, which includes hypertextuality, hypermedia, interface, programming, and so on.

(9) It is necessary to say that other techniques (paper, ink, print, pencil, and so on) also determine other kinds of limitation and configuration of the subject to these technologies, for it depends on the way we try to "translate", represent, interpret, or read the reality elements by making art in a general sense.

(10) Although technology is made by human, some scholars still insist on thinking of humanizing what is human.

(11) (C)ASA/HOUSE is a combination of Portuguese and English words. CASA (house) and ASA (wing) has sound interrelationship even with house and different meanings, although coincidentally the noun casa (Portuguese) means house (English).

(12) Dimension: International Poetry Magazine is a hard-copy review magazine from the city of Uberaba, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The main subject of the magazine is international poetry.

(13) The Infopoetry and Sound Poetry Course was given by E. M. de Melo e Castro at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, Brazil, in 1997.

(14) Possible translation: the word algorritmos is composed by algo (something) plus ritmos (rhythms), but the whole word algorritmos is related to sound poetry and rhythms in verbal poetry and also reminds us, from the sound point of view, of the word algoritmo (algorithm), which is related to computer programming.

(15) The title Antilogia laboríntica [poema em expansão] needs clarify the pun with "Antilogia" and "laboríntica". "Anti" (prefix which means "against") plus "logy" of "antology", so it is an anti-antology. "Labo" can be the first letters of "labor" (laboratory, that is, experimentation), or even "lab"; and "ríntica" is the last letters of "labyrinth" in Portuguese; so, it can mean "laboratory of labyrinth". The last words of the title is: "poem in expansion".

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First of all, I want to thank to Jim Andrews (Canada) who made an English revision of my text in 2001; and to Maria do Carmo Martins Fontes (Brazil) who patiently revised the text after other modifications I made after 2001. Joel Weishaus (USA) deserves my gratitude for reading and editing this text.

To my Professor Irene de Araujo Machado, my academic adviser, I would like to thank for the constant motivation during my PhD course.

SOURCES

The first essay I wrote on digital poetry genre was conceived in 2000, during my PhD course of "Gêneros na comunicação impressa, audiovisual e eletrônico-digital" (Genres in printed, audiovisual and electronic-digital communication), by Professor Irene de Araujo Machado, in the Communication and Semiotics Postgraduate Program at PUC SP (The São Paulo Pontifical Catholic University), and was published in a printed magazine (ANTONIO, 2001) and in a site (idem, 2001h). A reduced version (only the several digital poetry denominations) was also published (idem, 2001f).

The English version was submitted to several English printed and electronic magazines, but only a reduced and modified version was published in Slope (idem, 2003).

A review of my text by Funkhouser (2007, p. 22-24) made me think of revising my point of view, and the revision of my PhD thesis for publishing a book (coming soon) motivated me to review the concepts and think of digital poetry genre again.

This is what I could do in a short time. There is much more to revise and rewrite, but this requires more research, and it will be done soon.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDREWS, Jim. Vispo Langu(im)age. Victoria, Canada, 1995-2001. Disponível em: <http://www.vispo.com/>.

ANTONIO, Jorge Luiz. Infopoesia: a poesia no (do) computador. Dimensão: Revista Internacional de Poesia, Uberaba (MG), ano XIX, nº 28/29, p.277-280, 1999.

______. Brazilian Digital Art and Poetry on the Web. Victoria, Canadá, nov. 2000. Disponível em: <www.vispo.com/misc/BrazilianDigitalPoetry.htm>.

______. O gênero poesia digital. Revista Symposium: Ciências, Humanidades e Letras, Recife, PE, Universidade Católica de Pernambuco, ano 5, nº 1, p. 65-81, jan. / jun. 2001.

______. Considerações sobre a Poesia Digital. 404nOtFOund, Salvador, BA, ano I, v. 1, nº 3, abr. 2001b. Disponível em: <www.facom.ufba.br/ciberpesquisa/404nOtF0und/404_3.htm>. Acesso em 5 abr. 2001.

______. A map of different digital poetries. DMF 2001 – Digital Media Festival. Filipinas, 2001, College of Fine Arts, University of Philippines, 01 a 14 out. 2001f. Disponível em: <http://digitalmedia.upd.edu.ph/dmf2001/map.html>.

______. Os gêneros das poesias digitais. Site do Escritor, RJ, 2001. Disponível em: <www.geocities.com/rogelsamuel/poesiadigital2.html>. Acesso em 24 nov. 2001h.

______. Digital Poetry, Slope 17, EUA, fev. 2003. Disponível em: <http://slope.org/archive/issue17/antonio_essay.html>. Também disponível em Hermeneia Estudis Literarisi Tecnologies Digitals, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, set. 2003: <www.uoc.edu/in3/hermeneia/sala_de_lectura/jorge_luis_antonio_digital_poetry.htm>.

______. Entrevista com Chris Funkhouser. Concinnitas: Revista do Instituto de Artes da UERJ, Rio de Janeiro, nº 6, ano 5, p. 68-81, jul. 2004c.

______. Poesia eletrônica: negociações com os processos digitais. São Paulo, 2005. 201f. Tese (Doutorado em Comunicação e Semiótica) – PEPG em Comunicação e Semiótica, PUC SP. Acompanha um CD-Rom. São Paulo, 2005.

______. Poesia visual e eletrônica no Brasil. In: SANTANA, Evila; BRASILEIRO, Antonio; VUILLEMIN, Alain (Org.). (H)a crise da poesia no Brasil, na França, na Europa e em outras latitudes / La crise de la poésie au Brésil, en France, en Europe et en d´autres latittudes. Cluj-Napoca, România: Editura Limes; Cordes-sur-Ciel, França: Editions Rafael de Surtis; Feira de Santana, Bahia: Editora da UEFS, 2007a, p. 400-432.

______. Trajectory of Electronic Poetry in Brazil: A Short Story. E Poetry 2007, Paris, mai. 2007. Disponível em: <www.epoetry2007.net/articles/academic/jorge.pdf>. Acesso em: 01 out. 2007.

______. Tecno-arte-poesia: análises de procedimentos. Interact Revista de Arte, Cultura e Tecnologia, Lisboa, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, n. 15, 2008. Disponível em: <http://www.interact.com.pt/pt/ed15/interfaces/tecno-arte-poesia>.

ARAÚJO, Ricardo. Poesia visual e vídeo poesia. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1999.

BALESTRINI, Nanni. Tape Mark I algoritmo 1962. GAMMM, EUA, [s.d.]. Disponível em: <http://gammm.org/index.php/2006/09/03/tape-mark-i-algoritmo-nanni-balestrini-1962/>. Acesso em: 17 jul. 2008.

______. Tape Mark I texto. GAMMM, EUA, [s.d.a]. Disponível em: <http://gammm.org/index.php/2006/09/03/tape-mark-i-nanni-balestrini-1962/ >. Acesso em: 17 jul. 2008.

______. Tape Mark I. EUA, 2004. Disponível em: <www.unibuc.ro/eBooks/filologie/derer/balestrini/1.htm>. Acesso em: 15 jan. 2005.

BARBOSA, Pedro. A Ciberliteratura: Criação Literária e computador. 1.ed. Lisboa: Cosmos, 1996.

BEGHTOL, Clare. The Concept of Genre and Its Characteristics. Bulletin of The American Society for Information Science, EUA, vol. 27, n. 2, dez. / jan. 2001. Disponível em: <www.asis.org/Bulletin/Dec-01/beghtol.html>. Acesso em: 6 mar. 2001.

CAMPOS, Augusto de. Biografia, obras, poemas, sons, textos, links. São Paulo, 1999. Disponível em: <http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/home.htm>. Acesso em: 5 set. 2000.

CAPPARELLI, Sérgio. 33 ciberpoemas e uma fábula virtual. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 1996.

______. Infância digital e cibercultura. In: PRADO, José Luiz Aidar (Org.). Crítica das práticas midiáticas: da sociedade de massa às ciberculturas. São Paulo: Hacker, 2002, p. 130-146.

______; GRUSZYNSKI, Ana Cláudia. Ciberpoesia. Porto Alegre, RS, 2000. Disponível em: <www.ciberpoesia.com.br>. Acesso em: 05 abr. 2000.

______; ______. Poesia Visual. São Paulo: Global, 2001.

______; ______; KMOHAN, Gilberto. Poesia visual, hipertexto e ciberpoesia. 9º Encontro Anual da Associação Nacional de Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação – COMPÓS. Porto Alegre: PUC RS / FAMECOS, Grupo de Trabalho Comunicação e Sociedade Tecnológica, mai./jun. 2000. CD-Rom. Também disponível em: <www.pucrs.br/famecos/pos/revfamecos/13/caparelli.pdf>. Acesso em: 11 nov. 2007.

_____; LONGHI, Raquel. Poética digital infantil: não pode ser vendida separadamente. Conexão - Comunicação e Cultura, Caxias do Sul, RS, UCS v. 3, nº 6,p. 155-165, 2004.

CASTRO, E. M. de Melo e. Poética dos meios e arte high tech. Lisboa: Vega, 1988.

______. Finitos mais finitos: ficção/ficções. Lisboa: Hugin, 1996.

______. Videopoetry. Visible Language 30.2, New Media Poetry: Poetic Innovation and New Technologies, Providence, Rhode Island, Rhode Island School of Design, jan. / set. 1996a, p.138-149.

______. The cryptic eye. In JACKSON, K. D. et al (ed.), Experimental-visual-concrete avant-gard poetry since the 1960s: critical studies. Amsterdam; Atlanta, GA, EUA: Yale University, Rodopi, 1996b.

______. Algorritmos: infopoemas. São Paulo: Musa, 1998.

______. Uma transpoética 3D. Dimensão: Revista Internacional de Poesia, Uberaba, MG, nº 27, p.151-178, 1998a.

______. Iinfopoesia: produções brasileiras (1996-99). São Paulo, 1999/2000. Disponível em: <http://www.ociocriativo.com.br/guests/meloecastro/>.

CAUDURO, Flávio Vinicius. A estética visual do palimpsesto no design. 9º Encontro Anual da Associação Nacional de Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação - COMPÓS, Porto Alegre (RS), PUCRS / FAMECOS, mai. / jun. 2000. CD-Rom.

CHANDLER, Daniel. An Introduction to Genre Theory. Reino Unido, [s.d]. Disponível em: <www.aber.ac.uk/~dgc/intgenre.html>. Acesso em 20 ago. 2001.

COHEN, Ralph. Do Postmodern Genres Exist? In: PERLOFF, M. (Ed.). Postmodern Genres. USA, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989, p.11-27.

COUCHOT, Edmond. Da representação à simulação: evolução das técnicas e das artes da figuração. In: PARENTE, André (Org.). Imagem-máquina: a Era das Tecnologias do Virtual. São Paulo: Ed. 34, 1993, p.37-55.

DANIEL, Cláudio. A Poesia e o Computador. Dimensão: Revista Internacional de Poesia, Uberaba, MG, ano XV, nº 24, p.123-126, 131, 1995.

DOMINGUES, Diana (Org.). A arte no século XXI: a humanização das tecnologias. São Paulo: Unesp, 1997.

DONGUY, Jacques. Poesia e novas tecnologias no amanhecer do século XXI. In: DOMINGUES, D. (Org.) A arte no século XXI: a humanização das tecnologias. São Paulo: Unesp, 1997, p. 257-271.

DUCROT, Oswald; TODOROV, Tzvetan. Dicionário Enciclopédico das Ciências da Linguagem. Tradução: Alice Kyoko Miyashiro, J. Guinsburg, Mary Amazonas Leite de Barros e Geraldo Gerson de Souza. 3.ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1998.

ERICKSON, Thomas. Social Interaction on the Net: Virtual Community as Participatory Genre. Maui, Hawaii: January 6-10, 1996. Disponívem em: <http://www.pliant.org/personal/Tom_Erickson/VC_as-Genre.html>. Acesso em 25 jun. 2000.

______. Genre Theory as a Tool for Analysing Network-Mediated Interaction: The Case of the Collective Limericks. [s.n.], 1998. Disponível em: <http://www.pliant.org/personal/Tom_Erickson/Genre.chi98.html>. Acesso em: 27 jun. 2000.

FISHELOV, David. Metaphors of Genre: The Role of Analogies in Genre Theory. USA, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

FUNKHOUSER, Christopher. Takes a lot of voice to sing a millennial song. EUA, 1994. Disponível em: <http://writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/funkhouser/voices>. Acesso em 26 jul. 2004.

______. Toward a Literature Moving Outside Itself: The Beginnings of Hypermedia Poetry. Albany, EUA, 1996. Disponível em: <http://web.njit.edu/~cfunk/web/inside.html>. Acesso em: 25 set. 1999.

______. Hypertext and Poetry. Albany, 1996a. Disponível em: <http://writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/funkhouser/ nyc96.html>. Acesso em: 1º fev. 2001.

______. Cybertext poetry: effects of digital media on the creation of poetic literature. 1997. 229f. Tese (Doctor of Philosophy). College of Arts & Sciences, Department of English, University at Albany, State University of New York, EUA, 1997.

______. Moving Outside Itself: A Poetics of Hypermedia. São Paulo / New Jersey, EUA, 2003b. In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL BRASIL / FRANÇA, UEFS / UNIVERSITÉ D'ARRAS, 2., Feira de Santana, Bahia, 5 set. 2003. Digitado inédito, 10p.

______. E-Poetry 2003: An International Festival of Digital Poetry. Hermeneia Estudis Literaris i Tecnologies Digitals, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Espanha, 2004. Disponível em: <www.uoc.edu/in3/hermeneia/sala_de_premsa/E_Poetry_2003.pdf>. Acesso em: 16 set. 2004.

______. Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archaeology of Forms, 1959-1995. Tuscaloosa, Alabama, EUA: The University of Alabama Press, 2007.

______. Moving Outside Itself: A Poetics of Hypermedia. In: SANTANA, Evila; BRASILEIRO, Antonio; VUILLEMIN, Alain (Org.). (H)a crise da poesia no Brasil, na França, na Europa e em outras latitudes / La crise de la poésie au Brésil, en France, en Europe et en d´autres latittudes. Cluj-Napoca, România: Editura Limes; Cordes-sur-Ciel, França: Editions Rafael de Surtis; Feira de Santana, Bahia: Editora da UEFS, 2007a, p. 394-399.

______. Augusto de Campos, Digital Poetry, and the Anthropophagic Imperative. CiberLetras Revista de Crítica Literaria y de Cultura / Journal of Literary Criticism and Culture, Lehman College, City University of New York (CUNY), EUA, v. 17, jul. 2007b. Disponível em: <http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v17/funkhauser.htm>. Acesso em: 10 ago 2007.

______. IBM Poetry: Exploring Restriction in Computer Poems. New Jersey, EUA, mar. 2008. Disponível em: <http://web.njit.edu/~funkhous/2008/machine/>. Acesso em: 20 jul. 2008.

______. (Org). Description of an Imaginary Universe. Albany, EUA, 1994-1996. Disponível em: <http://writing.upenn.edu/epc/ezines/we/>. Acesso em 18 dez. 2002.

______ (Ed.). The Little Magazine: volume 21. Albany, EUA, University at Albany, Research Foundation of Suny (State University of New York), 1995, College of Arts and Sciences, CD-Rom, vol. 21. Microsoft Windows 3.1.

GYÖRI, Ladislao Pablo. Criterios para una Poesía Virtual. Dimensão: Revista Internacional de Poesia, Uberaba, MG, ano XV, nº 24, p.127-129,133, 1995.

JAKOBSON, Roman. Poética em ação. Traduçõesdiversas. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1990.

KAC, Eduardo. Introduction. Visible Language, New Media Poetry: Poetic Innovation and New Technologies. Visible Language, Providence, Rhode Island, EUA, v. 30.2, p.98-101, jan. / set. 1996.

______. Holopoetry. Visible Language, New Media Poetry: Poetic Innovation and New Technologies. 30.2 (revista). Providence, EUA, v. 30.2, p. 184-213, jan / set 1996a.

LAJOLO, Marisa. Do intertexto ao hipertexto: as paisagens da travessia. Revista da Biblioteca Mário de Andrade, São Paulo, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, v.56, p.65-72, jan. / dez. 1998.

______. ______. In: ANTUNES, Benedito (Org.). Memória, literatura e tecnologia. São Paulo: Cultura Acadêmica, 2005, p. 27-36.

LAUFER, Roger; SCAVETTA, Domenico. Texto, hipertexto, hipermídia. Tradução: Conceição Azevedo. Porto, Portugal: Rês, [s.d.].

LÉVY, Pierre. Quatro obras típicas da cibercultura: Shaw, Fujihata, Davies, In: DOMINGUES, Diana (Org.). A arte no século XXI: a humanização das tecnologias. Tradução: G. .B. Muratore e Diana Domingues. São Paulo: Unesp, 1997, p.95-102.

MACHADO, Arlindo. Máquina e imaginário: o desafio das poéticas tecnológicas. 2.ed. São Paulo: Edusp, 1996.

______. Poesia e tecnologia. Revista da Biblioteca Mário de Andrade, São Paulo, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, v.56, p.11-20, jan. dez. 1998.

MACHADO, Irene de Araújo. Texto como enunciação. A abordagem de Mikhail Bakhtin. Língua e Literatura, São Paulo, nº 22, p.89-105, 1996.

______. Redescoberta do sensorium: rumos críticos das linguagens interagentes. In: MARTINS, Maria Helena (Org.), Outras leituras: literatura, televisão, jornalismo de arte e cultura, linguagem interagente. São Paulo: Senac / Itaú Cultural, 2000, p.73-94.

______. Gêneros no contexto digital. In: LEÃO, Lucia (Org.). Interlab: labirintos do pensamento contemporâneo. São Paulo: FAPESP / Iluminuras, 2002, p. 71-81.

MENEZES, Philadelpho. Poética e visualidade: uma trajetória da poesia brasileira contemporânea. Campinas, SP: Unicamp, 1991.

______. A crise do passado: modernidade, vanguarda, metamodernidade. São Paulo: Experimento, 1994.

______. Poesia visual: reciclagem e inovação. Imagens, Unicamp, p. 39-48, jan. / ab. 1996.

______ (Org.). Poesia sonora: poéticas experimentais da voz no século XX. São Paulo: Educ, 1992.

______. Poesia sonora hoje: uma antologia internacional. São Paulo: Estúdio de Poesia Experimental do Programa de Comunicação e Semiótica da PUC SP, 1998. CD-Rom.

______. Poesia sonora: do fonetismo às poéticas contemporâneas da voz. São Paulo: Laboratório de Linguagens Sonoras do Programa de Comunicação e Semiótica da PUC SP / FAPESP, 1996. CD-Rom.

MENEZES, Philadelpho: AZEVEDO, Wilton. Interpoesia: poesia hipermídia interativa. São Paulo: Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie / Estúdio de Poesia Experimental da PUC-SP / FAPESP, 1997/1998. CD-Rom.

______; ______. Interpoesia: poesia hipermídia interativa. II Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul: Julio Le Parc - Arte e Tecnologia. Porto Alegre, RS: Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, 05.11.1999 a 09.01.2000, p.62,98. Catálogo.

MOLES, Abraham A ; ANDRÉ, Marie-Luce (Col.). Art et ordinateur. Paris : Casterman, 1971.

______; ROHMER, Elisabeth (Col.). Art et ordinateur. Paris: Blusson, 1990.

______; ______. Arte e computador. Tradução: Pedro Barbosa. Porto: Afrontamento, 1990a.

NUNBERG, Geoffrey. Les langues des sciences dans les discours électronique. In: CHARTIER, Roger; CORSI, Pietro (Dir.). Sciences et langues en Europe. Paris: Centre Alexandre Koyré / École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales / Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique / Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, 1996, p. 247-255.

PADIN, Clemente. La poesia experimental latinoamericana: 1950-2000. Montevidéu, Uruguai: Información y Producciones, 2000.

PARENTE, André (Org.). Imagem-máquina: a Era das Tecnologias do Virtual. Rio de Janeri: Ed. 34, 1993.

PIGNATARI, Décio. O que é comunicação poética. 3.ed. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1991.

PLAZA, Julio. Videografia em videotexto. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1986.

______. As imagens de terceira geração, tecno-poéticas. In: PARENTE, André (Org.). Imagem-máquina: a Era das Tecnologias do Virtual. Trad. Rosângela Trolles. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. 34, 1993, p.72-88.

______. Info x fotografias. Imagens, Campinas, SP, Unicamp, nº 3, p. 50-55, dez. 1994.

______; TAVARES, Monica. Processos criativos com os meios eletrônicos: poéticas digitais. São Paulo: Hucitec / FAPESP, 1998.

RAMOS, Fernão Pessoa. Falácias e deslumbre face à imagem digital. Imagens, Campinas, SP, Unicamp, nº 3, p. 28-33, dez. 1994.

ROSENBERG, Jim. The interactive diagram sentence: hypertext as a medium of thought. Visible Language, New Media Poetry: Poetic Innovation and New Technologies, Providence, Rhode Island, EUA, n. 30.2, p. 103-117, jan. / set. 1996, p.103-117.

SÁ-CARNEIRO, Mário de. Asas. Lisboa: Sá da Costa, 1956.

______. A confissão de Lúcio. Lisboa: Ática, 1973.

SEGRE, Cesare. Géneros. In: ROMANO, Ruggiero (Dir.). Enciclopédia Einaudi: volume 17: Literatura - Texto. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1989, p.70-93.

SWALES, John M. Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

TODOROV, Tzvetan. Os gêneros do discurso. Tradução: Elisa Angotti Kossovitch. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1980.

TOMS, Elaine G. Recognizing Digital Genre. Bulletin of The American Society for Information Science, EUA, vol. 27, n. 2, dez. / jan. 2001. Disponível em: <www.asis.org/Bulletin/Dec-01/toms.html>. Acesso em: 6 mar. 2001.

USPENSKY, Boris. A Poetics of Composition: The Structure of the Artistic Text and Typology of a Compositional Form. Tradução: Valentina Zavarin and Susan Wittig. EUA: University of California Press, 1983.

Author Biography

Jorge Luiz Antonio