Former Washington Post journalist Paul Hendrickson teaches a creative writing course that invites undergraduates to research and report "memorable, full-bodied stories" based on a single photo. Hendrickson's prize-winning book Sons of Mississippi was launched by the 1962 Life photograph that appeared on its cover. Read stories by Molly Johnsen and Allison Stadd, students from the fall 2007 course, and view the photos that launched them.

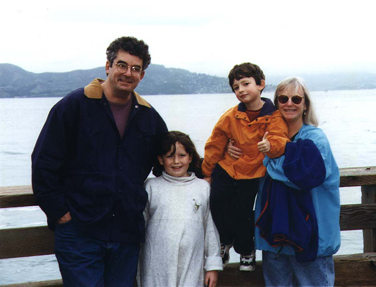

It's only a deceiving photograph if you don't look hard enough. At first glance you probably wouldn't notice the misery jammed into my dad's mouth, or the way my parents use their children to keep distance between them. It is December 26th, 1996 and we are at Pier 39 on the San Francisco Bay. We came for the sea lions. You can't see them in the water behind us, but I remember the way they spread their bodies over the rocks or hoisted themselves up with their flippers, noses pressed against the sky. It should have been a perfect vacation. We were in a beautiful city with lots of extended family and a gorgeous house all to ourselves, courtesy of my mom's friends, the Butlers, who had gone out of town. But it hadn't stopped raining and there was no fireplace for our stockings and every night I felt my parents' sharp words slice through the wall separating our bedrooms.

My mom and Homer are wearing jackets they borrowed from the Butlers. We had assumed we wouldn't need raincoats in California, but the weather lingered somewhere between a halfhearted drizzle and a smothering fog. Tobias Butler is only a year older than Homer, and Elena is a year older than I, and I remember feeling like I was living her life. My mom has Elena's blue fleece jacket flung over her arm -- clearly the enchantment I'd felt at being allowed to wear what I wanted from another girl's closet has worn off. It wasn't just the coat, though--it was her bedroom and dollhouse and metallic blue nail polish. The second we arrived at their house I clambered up the slippery wooden stairs, eager to inspect my temporary bedroom. I loved the hammock full of every stuffed animal imaginable, and the way the pink, plush carpet felt under my toes. I spent that evening painting my nails blue with Elena's polish, and played a little game with myself as I went: if I sat up straight and pursed my lips just right I could almost believe I was Elena Butler, one whole year wiser and more sophisticated.

When I use my thumb to cover Homer's mouth in the photo, the desperation in his eyes consumes me. All of our family's unspoken issues swim around in that tiny body, weighing him down. I know we both wished we could burrow into Tobias and Elena's lives the way we burrowed into their huge beds at night -- safe and snug and right. Wouldn't it be nice to live in a gigantic house filled with plush carpets and warm jackets? Homer's crooked thumb, the size of a tube of Chapstick, is trying to do so much for the four of us. Seeing my brother's need to show everyone, "See? We're all ok!" makes something heavy in the bottom of my chest.

My mom is doing the same thing in her own way. Even today, years after their divorce, my dad will tell you that his ex-wife has a talent for being cheerful. She tells the camera that everything is fine, and flashes the same grin she wore for her wedding pictures. She and Homer are a little team, ready to take on any glitch in the plan.

My dad hadn't wanted to go. It was supposed to be our first Christmas in the new house -- the one he had designed down to the doorknobs. My mom presented him with the idea in September, just a few weeks after we'd finally gotten settled. The move was one of the last things they did to try to make it all work. A clean slate. When my dad said he didn't want to leave home for Christmas, my mom informed him that she would be going and taking me and Homer with her. He could come if he wanted. He didn't want to, but he came all the same. Each of my mom's four sisters burst into San Francisco that Christmas, their husbands and children trailing just a few steps behind. The whole thing was an early celebration of my grandfather's seventieth birthday. He flew out first-class from Rhode Island and we toasted him over elegant meals on his dime.

My dad is wearing my grandfather's old jacket. My grandpa was always giving piles of clothing away in an ongoing effort to keep his life, and his bureau, in order. My dad's smile looks to me more like he's baring his teeth, challenging anyone to get in his way. I can't shake the feeling that if he withdrew his hand from his pocket it would be swollen and red, throbbing with all of the anger he's hiding. At dinner the night before, he chatted with "the boys" -- an eclectic set of brothers-in-law who have little in common besides their wives' family. He probably had one glass too many, holding each sip in his mouth for a second, a brief reprieve before swallowing. Homer and I secretly enjoyed our fancy clothing, but my Dad hates wearing ties and his sport coat made him sweat in the small, candlelit room.

On Christmas Eve my dad decided that we needed a buche de noel. Surely that would make things better. He called dozens of places, before finding a gourmet grocery store. One of the things that helped him get through Christmas dinner was the thought of the chocolate treat waiting for us at the house. He knew Homer and I would jump up and down and that we'd all sit at the table and eat it together. Just us.

You can't see my rainbow tights in the photo. The outfit was a Christmas gift from an aunt, and even though it was too big and too warm I wore it that day. The pin was a present, too. I used to always try to use and wear every present I could the day after Christmas in an effort to make December 26th feel less like a letdown.

Christmas was different that year, though, and it wasn't just the lack of snow on the ground. It was my first year knowing the truth about Santa Claus. I'm standing tall in the photo, making a conscious effort not to appear childlike. I was knowledgeable now, informed of the deceitful nature of life. There was no Santa and my parents hadn't slept in the same bed for months, and I kept catching them watching me, sadness sunk like stones in the bottom of their eyes.

The Butlers had no fireplace so we laid our stockings out on the living room floor. Homer worried that Santa would find this unacceptable but I reassured him, glancing at my parents to make sure I was saying the right things. Homer woke me up around six o'clock on Christmas morning. "It's Christmas! It's Christmas!" I still felt the familiar sparks of excitement, but I couldn't deny the grief that sat in the back of my throat as we ran down the stairs and into the living room. It wasn't our house, there wasn't a Santa, and why were Mom and Dad sitting so far apart on the couch? I may have overdone it a bit, with my, "Oooh look what SANTA gave me, Homer!" and "Wow, I wish Santa was here so I could thank him!" but my brother didn't seem to take notice. I thanked my parents later in private, and I can still remember tracking them down in opposite corners of the huge house.

Everything's not broken yet. The fact that my parents even posed for the picture is evidence of this. None of us were ready for the grueling trip home. I remember something about a fuel problem, and the way my parents' faces scrunched up. Soon we were landing in Salt Lake City. My dad was sighing and grunting a lot, but my mom sat perfectly still so as not to disturb Homer, who was sleeping in her lap. We exited the plane to a chorus of "So sorry for the inconvenience." I don't remember the shuttle bus. I must have been groggy. I probably enjoyed our little adventure; it bought my family more time before we returned to our half-unpacked house, where unspoken frustration stuck to the walls and pooled on the floor.

Eventually we made it to a hotel in Kentucky. The theme of the dank, gloomy building was medieval torture. We'd had to leave our luggage in the airport, so when we got to our room I enjoyed "making do" without a toothbrush or pair of pajamas. Homer and I made our way to one of the slumped beds -- we always shared when our family stayed in hotels. Our parents stopped us before we got too far, informing us that "the girls" would be in one bed and "the boys" in the other. They were too weary and irritated to try to explain themselves. I'll never forget the way my mom held me that night, hard and tight, and her hot, heavy breaths smacked my ear.

It is the last photo ever taken of the four of us. It marks the last vacation, Christmas and plane ride we spent together. I remember lying in bed the night after we arrived home, waiting for someone to come and tuck me in. Usually one parent attended to Homer while the other came to me, but this time they both entered my room. I don't remember a lot of things about the conversation, but I do know that I was lying on my back with the covers pulled up tight under my chin. They loomed over me and their eyes were sad. I don't know whether I asked them a question or if they just decided to tell me. Either way, they said something confusing about a chain that had broken during our trip to San Francisco. I remember the way they shared the sentence, each saying half of the words. I felt like I was supposed to understand everything, so I didn't ask questions. Under the covers I dug my fingernails into my palms.

The original copy of the picture is missing now. For a while after the divorce Homer had it framed in his room, but no one was sure if that was the right thing. It eventually disappeared. So now the picture sits, abandoned, in a hiding spot somewhere -- my dad can't remember where he put it. I would never wish for things to go back to the way they were, but, even so, I like thinking that I'll stumble across the photo some day. Up high on a dusty shelf in my dad's closet, perhaps, or maybe covered with cobwebs in the basement. Regardless of where my dad decided to put it, it's nice to think that somewhere, in some corner of our house, the four of us are together.

Molly Johnsen is a sophomore majoring in English with a creative writing concentration. She has a minor in Spanish and spends most of her free time training for a half-marathon.

Twelve photographs.

Each is black and white, eight and

a half by eleven inches, and worn around the edges with years of eager

handling. They lie inside a Fredric Perry Photographers wedding

album, its seam threadbare and cardboard covers jaundiced with

age. One photo in particular, this one in front of us, holds my

attention. I slip it out, turn to my grandmother, and click my

mechanical pencil. "This is the one," I tell

her. "Tell me about this one."

Sixty years ago.

It seems impossible, probably even

more so to my grandmother, that sixty years have passed since this

grinning groom and his sassy wrinkled-nose bride sunk the knife into

their three-tiered wedding cake, my grandfather gently grasping his new

wife's gloved hand. But over half a century has indeed

passed since May 20th, 1947. I suppose those five cent Coca Cola

bottles, uncapped at each table setting like cheap centerpieces, are

proof of the passage of time. Actually, much else in the picture

is outdated. How about that dress?

One hundred

dollars.

Maybe it cost a little more, maybe a little less. It's no

surprise that after so much time has elapsed, fact has faded into

conjecture. But my grandmother does remember the actual

dress with certainty. Her clarity on this point is likely owing to

the stir caused by the slightly-too-sheer tulle and slightly-too-short

cap sleeves, unsuitable for a young Jewish bride. So even on this

most pious of days, my grandmother lived up to her nickname:

"Torchy." She claims that the alias derived from her

maiden name, Tulchinsky. But the girl in this photograph looks

like a fireball to me. And it would have been easy to breach

formality a little with her dress design, as her mother granted her free

reign to collaborate with the seamstress. I'm sure the hired

help was worth the money, too; having a gown tailor-made would have been

a real treat. Normally my great-grandmother Rachel outfitted her

two daughters with practical store-bought clothing. In fact, the

woman made shopping so businesslike that she would actually knit while

bustling between stores with her daughters in tow. Rachel's

deft fingers could guide the needles with nary a glance downward.

Well, like mother, like daughter. The miscellany of woolen

patchwork quilts and scarves adorning my family's couches and coat

closets, each product emblazoned with a sewn-on "Hand-Knit by

Sarra Chernick" label, were skillfully crafted by my grandmother

in the tradition of her mother Rachel. My grandmother, the expert

needle-wielder, can knit on public buses and air buses, can knit while

waiting in her terry-cloth apron for the chicken broth to heat and can

knit while waiting in her black-tie attire for the Kennedy Center Opera

House lights to dim.

But right now, by my side on a loveseat in her apartment, she is

wistfully peering into her past, hands holding this beautiful,

cherished, ancient moment rather than a pair of knitting needles. Right

now she has transported herself to another time and place: a springtime

evening in Winnipeg, Canada. Right now my pencil scribbles,

wringing details from the recesses of her memory. I study the

image in front of me, foraging for facts that my grandmother's

recollections can breathe life into. Ah, how could I forget?

One of our family folklore gems. It's difficult to see in

this shot, but I know exactly where to look: the right hand of my

great-grandfather Samuel, the one with his fedora brim jutting out from

in between his wife Rachel and older daughter Byrtha.

Only

four fingers.

My grandmother knows the story as thoroughly as she knows the birthdates

of her five children, as well as those of her sister Byrtha's five

children. Byrt is the one in the picture with the Frida Kahlo

eyebrows, smiling up not at the camera like her parents, but at the

younger sister she so adored despite the fact that she, the older one by

four years, was yet unwed. My grandmother has to retrieve a

magnifying lens from her desk, but with it I can just make out the

evidence of when, thirty years or so earlier, the two girls'

father took a sip of whiskey, a deep breath, and finally a handgun from

his army supply pack and blew off his right index finger. The

agony is beyond comprehension, but my grandmother avows that it was

worth anything to her father- even mangling his trigger finger to

preclude his capacity as a soldier- to escape fighting for the

anti-Semitic Cossacks in Russia during World War One. Sadly,

decades later at his daughter's wedding, Samuel's

disfigurement precluded his capacity as a Jewish father. For even

though he was a kohen- a Jewish priest- my great-grandfather Samuel was

only allowed that May 20th by Jewish law to stand on the bimah with his

family, but not recite prayers or read from the Torah. My mother

remembers Sam as warm and affable, always keeping the jars of penny

candy on the front counter of his grocery store fully stocked for

customers' children. But he seems subdued in this picture,

tucked in the shadows between Byrtha and Rachel. Maybe he is so

cloaked in reserve here because he laments being unable to contribute

his part to his daughter's wedding ceremony.

But my great-grandfather certainly wasn't ill at ease for the

entire evening. My grandmother tells me about the live band her

family hired, gushing about how everyone "danced the whole

night." I so want to be there with her. I want to see

my grandfather frisbee his fedora off to the side and grab his bride

around the waist, lifting and twirling

her so her skirts

balloon. I want to picture it. I ask her: where was this

photo taken?

123 Matheson Avenue.

We have to look it up, of

course. Even though every winter she doles out an

envelope

of Hanukah gelt to each of her eight grandchildren, remembering every

child's age in dollar bills without fail, even the sharpest

82-year-old wouldn't be able to recall the exact address of the

Jewish Orphanage and Children's Aid Society of Western Canada. I

am taken aback at first by the peculiarity of the venue. But

according to my grandmother, all Jewish weddings in Winnipeg then took

place at the Jewish orphanage.

I so badly want this place to have been elegant, tasteful. But, I

reluctantly admit to myself, the flower-freckled curtains do seem a bit

tacky, the wrinkled white tablecloth low-cost and

machine-washable. And what about the food? Thick slices of

challah bread are heaped on ceramic dishware, salt and pepper shakers

dotted haphazardly along the table almost as in a mess hall. One

plate in the foreground bears a mangled mass of chicken cutlets, the

small bowl next to it containing what looks like spinach. But at

this, my grandmother looks aghast. "It was NOT

spinach." I get a glimpse of the fiery spirit of

"Torchy": spinach is my grandmother's least favorite

food, and she assures me that she would not have ordered it for her

nuptial meal. In any case, all this lack of grandeur is not

surprising in light of the fact that the Tulchinskys, the bride's

family, financed the whole wedding. How much did my

grandfather's family pay?

Not one cent.

My grandmother describes her

father-in-law, seated left of her here, the fabric of

his suit

jacket and tines of his fork just barely visible, as a "big strong

man," a manual laborer who made anchors for fishermen. But

his lack of fiscal know-how made it hard to provide for his

family. Without my grandmother's financial support, my

grandfather would not have received his University of Manitoba

diploma. My grandfather's siblings, too, struggled penny for

penny to pursue an education. His oldest brother Jack, seated here

third from the right, used to trudge runny-nosed through the snow to the

university with nothing more in his lunch sack than a sandwich of

chicken fat glooped onto brown bread. The Chernick family's

near-poverty explains why only one of my grandfather's siblings is

in this photograph. Jack was the only one to come to the

wedding. The travel was far too expensive for the other brothers,

but Jack and his wife Anne and son Paul came from relatively nearby

Minneapolis.

And it's a good thing they did. My grandmother laughs as

she recalls her favorite

anecdote from her wedding day, featuring

her four-year-old nephew Paul. I can tell from this picture that

Paul was a troublemaker. He is nestled in the nook between his

parents, happily about to cram a hunk of bread into his mouth. I

can imagine him swinging his legs back and forth beneath the

table. Hours earlier during the ceremony, as Paul's father

Jack and his uncle- the groom- stood shoulder to shoulder on the bimah,

the little boy hollered amid the hushed murmurings of prayer,

"That's my dad!" Of course his proud

proclamation referred to Jack but, much to everyone's amusement,

one could easily interpret the child's exclamation to mean he was

the son of the groom- a preposterous prospect then for a young unwed

Jewish couple. Perhaps it's not too far off the mark, then,

to suppose that Paul is so snugly situated between his parents in this

photo as a preventative measure. I suggest wryly to my grandmother

that perhaps it would have been more effective to seat him next to Mrs.

Tulchinsky, her mother. It's easy to recognize from Rachel

Tulchinsky's smug smile and that glorious, ridiculous hat that she

would have been the right one to give little Paul a smart smacking if

needed. I know, without asking, how much nonsense she took.

"Bupkis."

One of the only Yiddish words I

know from my grandmother- ironic, considering her veneration of her

grandkids would never let her disappoint them with

"nothing". But supposedly that wasn't the case

with her mother Rachel who, according to my grandmother, "really

thought she looked terrific" sporting her latest purchase from the

millinery. Taller than her husband, Mrs. Tulchinsky's

cocksureness made her the only Jewish woman in their Winnipeg community

to keep her family on a strict diet, Jewish mothers normally being known

for their hearty cooking.

I love hearing my grandmother's narrative tidbits about my hell-on-wheels great-grandmother, just as I've loved watching the texture of her wedding day, and her life before I knew her, emerge from this photograph like the ripples of a reflection in water melting into each other to form a clear image. Maybe this is what imbues photography with its power: not the stories that materialize out of a rectangle, but the ability of that rectangle, by virtue of those stories, to fuse an emotional bond between its viewers. Perhaps this one treasured instant from May 20th, 1947, cradled in the box of its four boundary lines for all eternity, is so valuable not for the narrative flesh it affords from its depths, but for the new story it has created in my and my grandmother's joint reading of its contents. I haven't merely looked at this photograph with my grandmother, I haven't just pored over it. I have experienced it with her all over again. And that.

Is unquantifiable.

Allison Stadd is a junior English major concentrating in creative writing. Her passions other than writing include playing jazz drums, tap dancing and reading anything in sight.