at 4616 Osage, April 2007

LEADER: We light the candles. Praised

be the

king of the universe for giving us the blessing of light.

ALL THE GIRLS AND WOMEN:

Happy are those of faith who still can bless the light of candles shining

in the darkness. Rejoice in those who keep the way, for there is still song

for them within you.

Bob T.:

May the candles we now light inspire us to use our powers to heal and not

to harm, to help and not to hinder, to bless and not to curse.

HANNAH SINGS: Baruch atah adonai, elohaynu melach ha-oh-lum, asher

kidshanhu

vamitzvotav, vitzivanu, l'hadlich-nair, shel pesach.

LEADER:

Now in the presence of one another, before us the elements of festive

rejoicing, we gather for our sacred celebration. With believers, young and

old,

linking the past with the future, we listen once again to God's call

to service.

LEADER: Lift the glass of wine you have before you and join in the

recitation of the kiddush, but do not drink quite yet.

David: L'kadesh means to sanctify, to make holy. Holy means something is special and connected to God. We

make Kiddush, a

blessing on wine, to show that this is a special day, and that the Jewish people are a special nation. Wine is used

because it is something special, not ordinary like soda or juice. It also can make people happy.

Jamie-Lee: We each fill each other's cups as if we were being served - this is to say how important each person

at the Seder is.

You can help pour too!

Ben: Everyone, even children, should drink 4 cups of wine (or grape juice) at the Seder. After Kiddush, everyone

drinks the

first cup while leaning to the left.

Bob P.: Why do we lean while we drink? That looks silly!

Sam: In the time of the Romans, wealthy people used to eat while lying on couches. At the

Seder, when we

are celebrating our freedom from slavery, we lean to symbolize our status as free men and women (and children)!

Jane: The cups signify the four expressions in the Torah which describe our freedom from Egypt. Let us

consider just the first cup. This first cup,

which also

serves as Kiddush, goes with the phrase "I will take you out," when God helped us recognize that we were Egyptian

Jews, and not

Jewish Egyptians. This is the essence of Kiddush sanctification - the realization that the Jewish People play a unique

role in this world.

EVERYONE:

Blessed art Thou, Eternal our God, Ruler of the universe, Creator of the

fruit of the vine.

LEADER: Now we drink the wine.

LEADER: Now "Urchatz": At this point everyone at the table washes his or her hands (and here we do not recite a blessing). The Maharal of Prague has said that there is deep symbolism involved when one washes his hands for the purpose of a Mitzvah.

Jamie-Lee: Hands represent the beginning of the human body, for when one stretches out his hands to reach forward or above, it is the hands that are at the front or at the top of the body.

Leader: The Maharal explains that that the way one begins an action greatly influences the direction and tone of all that follows from that point, and therefore, even a seemingly insignificant sin, but one involving the "bodily leader," is particularly wrong, for a misguided beginning will lead to an incomplete and incorrect conclusion.

David: On Pesach, the Maharal continues, we should be extremely careful in our observance of this idea, for Pesach is the annual point of beginning for everything that exists, in all times.

Leader: Now it's time for us to dip the Karpas (Parsley).

Lois: Spring is here. The world is alive and new; the bonds of winter cold are broken. Nature is reborn and the earth feels free and young again. The trees are budding; behind the buds lie flowers. The surprise of the world is about to burst open.

Ellie: In Mitzrayim, our ancestors awoke from their sleep in chains to the life of freedom; in the long wandering out of bondage, our people were reborn into a new life.

All: BARUCH ATTAH ADONOI ELOHENU MELECH HO'OLOM BORE P'RI HO'ADOMO

Leader: Take the parsley, symbol of spring and hope, and dip it into the salt water, symbol of the bitterness and tears of our people, and eat it.

JANE: Through the ages, our people's Spring festival has expanded to express an ever greater understanding of the concept of liberation.

DAVID: The earliest meanings of the holiday relate back to pre-Israelite times and refer to two distinct holidays: the Feast of the Paschal Lamb and the Festival of Matzot, or Feast of Unleavened Bread.

Lorenzo: Each of these feasts, occurring at the lambing season and the beginning of the wheat and barley harvest respectively, celebrate the renewal of the year's growth and, so, a liberation from the fear of economic destruction.

SAM: In biblical times, both of these holidays gained historical associations and related to the liberation of the Hebrews from slavery in Egypt.

ELLIE: During the biblical period the Exodus event became the central idea of Jewish life and the experience from which the core values of our people grew.

BEN:Approximately a hundred years following the rise of Christianity, during the time when the Roman Hadrian persecuted the Jews, the rabbis added a more political understanding to the Passover observance.

BOB T.:Five rabbis spent Seder night together deeply involved in discussing the Exodus from Egypt. Finally, at dawn, their pupils told them that the time for the morning prayers had arrived. This event was written down about 90 years later, and added to the Haggadah about 400 years later.

LORENZO: At first glance it is not obvious why the story of the five rabbi's all-night seder has a political meaning.

BOB T.: But all rabbinical commentators are unanimous in understanding that that seder was a secret or clandestine meeting of leaders of the rebellion against Rome who were meeting under the cover of the Passover holiday to celebrate the liberation from oppression of an earlier despot and plan the revolt against a contemporary oppressor.

JANE:So it was during the Roman oppression of the Jews that Jewish people began to see Passover as a lesson in fighting against dictators, empires, oppression, slavery and genocide.

Jamie-Lee: Those five rabbis who first gave Passover its political and ethical significance were willing to rebel against their Roman overlords--and their inspiration came from Moses through Passover. What contemporary injustices do we think of tonight at our seder?

Ellie: Living our story that is told for all peoples, whose conclusion is yet to unfold, we gather to observe the Passover, as it is written:

EVERYONE: "You shall keep the Feast of Unleavened Bread, for on this very day I brought your ancestors out of Egypt. You shall observe this day throughout the generations as a practice for all times."

BOB P: For Jews this is a lifetime commitment.

LEADER: We hold in our hands a "Haggadah," the special service for Passover, which is called "Pesach." The meal is called "seder," which means "order," as in "the order of worship."

HANNAH: Each family - with their relatives and friends - has its own style and variation of the Passover rituals. Ours has grown each year, although we have kept some of the drawings the children made when they were young.

BEN: No one has ever drawn a better locust than Hannah did when she was six.

ELLIE: And we all conduct the seder together. Everyone around the table participates in what the great theater producer Joseph Papp liked to call "the longest running show in history."

LOIS: The Haggadah is not merely the story of the exodus out of Egypt, but it equally encompasses the hopes of the past and the dreams of the future.

JANE: When we use the phrase "hopes of the past" we don't just mean the distant past of our people in Egypt 7,000 years ago. Exodus is an ongoing status.

LEADER: The Jews of Poland had an expression: "We prayed with our feet." This was their way of remembering how they celebrated Passover during their hard journey to America from Poland during the times of awful persecution there.

LORENZO: The Haggadah connects the past to the present. It's like a lesson book.

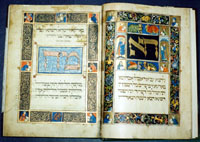

BEN: Haggadahs come in all shapes and sizes. Below is a picture of a Haggadah from the Middle Ages.

BOB P.: Like many people, the Jews in ancient pastoral times celebrated the liberation of the earth itself from wintry darkness.

ELLIE: Many Jewish people see it as a duty to plant something in the spring, and to watch it grow, and so to catch the spirit of rebirth and renewal.

HANNAH: But of course we also must take good care of the plants we grow in our gardens.

LOIS: Thus at Passover we read from the Song of Songs.

EVERYONE:

Come, my lovely ones, come. Behold, winter is past, the rains are over and gone. Flowers appear on the earth. The season for singing has come, and the song of the dove is heard in our land. JANE &: The fig tree is forming its first green figs ELLIE: and the blossoming vines smell so beautiful. BOB P. Come then, my lovely ones, come. & DAVID:

SAM: Now we are ready to tell the Passover story.

LORENZO: About 3000 years ago the Jewish people were slaves in Egypt. They lived and worked along the Nile River.

BEN: As slaves, they were always suffered terribly.

SAM: They were not permitted to live free as Jews. They felt confused about their identity, and they were too tired to do much for themselves. During long, arduous days of work they helped build the pyramids.

BOB T.:Each year at Passover, Jews all around the world, and their friends, have a seder to tell the story of their their liberation from this enslavement.

Bob P.: We eat, enjoy each other's company, remember the bitter times, and hope that we will never forget about the story of our slavery.

LEADER: Traditionally Jewish families invite their closest friends and neighbors to join them for the seder.

HANNAH: Why do they invite them?

LEADER: In the book of Exodus, in the Torah, we learn of this basic instruction to all Jews: "And a stranger you shall not upset, nor shall you exploit him because you know the soul of a stranger, for you were yourselves strangers in the land of Egypt."

BOB T.: That idea is the most basic part of the "constitution" of the Jewish nation. To know the soul of another person, to understand that person's innermost feelings. To know what it is to feel strange in a strange land.

JANE: Can there be anything greater, more meaningful, more ennobling than that? Can there be any greater freedom than that? And that is why we want to share the story of our sufferings throughout history.

DAVID: That is also why in the Haggadah "it is the duty of everyone, in every generation, to see himself as if he or she personally participated in the Exodus from Egypt."

Jamie-Lee: Not merely a historic memory, but a living reality. Not just a dry history lesson, but a very personal odyssey. Only thus does it have real meaning.

LORENZO: The story might not have had any meaning for us had it not been for Moses. Moses was a young Jew who had grown up in the Pharoah's family.

Jamie-Lee: After much struggle with his conscience, and after speaking with the voice of God, Moses realized he would lead the Jewish people out of Egypt.

HANNAH He came to Pharoah, and demanded, "Let my people go!"

LOIS: Pharoah stubbornly refused. Moses warned him that if he did not let the Jewish slaves free, God would punish him and all Egyptians with plagues.

JANE: Moses showed Pharoah why he should let the Jews leave. One day Moses made the water of the Nile River turn to blood.

LOIS: But Pharoah still refused to let the Jewish people go free. And then came the plagues.

DAVID: They were blood, frogs, bugs, wild beasts & snakes, blight, boils, hail, locusts, darkness, and slaying of the first-born.

LEADER: Now in the seder we recite the plagues one at a time. Each time we say the name of the plague, we dip our little finger in a glass of wine, and drop one drop of wine on our plate.

EVERYONE:

1. Blood

2. Frogs

3. Bugs

4. Wild beasts and snakes

5. Blight

6. Boils

7. Hail

8. Locusts

9. Darkness

10. Slaying of the first-born

BEN, DAVID and HANNAH recite them in Hebrew:

HANNAH: In our Hagadah we have a picture of one of the bugs:

LORENZO: Here is a picture of one of the wild beasts (VERY wild indeed):

BEN: And here is the picture Hannah once drew of a locust. (It seems not to have any legs!)

HANNAH: And here is Katie Judd's old drawing of one of the snakes:

BOB T.: Finally, Pharoah said that the Jewish people could go free. Moses and the Jews decided to leave in a hurry. They packed so fast that they did not have time to bake their bread properly.

ELLIE: The bread they took for the trip had no yeast.

JANE:So it was flat, and baked in the sun. We call this matzah.

SAM: Matzah comes in all shapes and sizes. Americans typically eat square matzah. Elsewhere in the world people eat round matzah, such as in the picture below.

Ben: This year our matzoh cames from the Four Worlds Bakery, and was baked by Michael Dolich of the Kol Tzedek congregation. Michael tells us that this very much like what the Hebrews would have eaten during their escape. (And Bob helped Michael do the baking. It's possible that Bob himself baked the very piece of matzoh you'll eat tonight!)

LEADER: On Passover we eat only this sort of bread -- bread without yeast, or unleavened bread. And this part of the seder is called the "YACHATZ." I take the middle matzah from the seder plate, and I break it into two, one piece larger than the other. The larger piece is set aside to serve as afikoman. The smaller piece is put back, between the two matzot. The afikomen is put in a hiding place--one for each of the children at the table. After the seder and the Passover meal, each child at the table will search for the afikomen.

David: The next part of the seder is called the "MAGGID."

[An adult raises the seder plate with the matzot.]

DAVID and HANNAH say the prayer over the seder-plate matzoh in Hebrew:

Bob P.: This is the bread of affliction that our fathers and mothers ate in the land of Egypt.

LOIS: The Matzah we eat reminds us that though we have enough, many people go hungry. We who were slaves in Egypt and now have plenty, have a responsibility to those who do hunger.

Jamie-Lee: In this elaborate and plentiful feast the Matzah is a slender reminder of poverty. In our busy lives the Seder itself is the merest reminder that we are descended from a mixed multitude of slaves.

SAM: As we break the bonds of slavery may this meal that we share help us form bonds among each other so that we can eliminate all forms of enslavement on the earth.

LEADER: Whoever is hungry, let him come and eat; whoever is in need, let him come and lead the seder. This year we are here in Philadelphia. In other places people are not free. This year there are people who are not free.

BEN, LORENZO AND HANNAH TOGETHER:: Next year maybe they will be free.

LEADER: We who know what it was like to be slaves in Egypt should help other people become free.

BOB P.: Elijah the Prophet occupies a fascinating place in Jewish historical consciousness. Our tradition teaches that as history approaches the climactic era of universal peace and brotherhood, it will be Elijah the Prophet who will announce the heralding of the new era.

DAVID: Also, when the Talmud is unable to definitively resolve certain questions of law or practice, it often states that the questions have to wait for Elijah.

Jamie-Lee: With the advent of the final era of peace and brotherhood, one of Elijah's roles will be to resolve all those lingering scholarly quandaries.

LEADER: I will tell you a story about Elijah. One year the Kotsker Rebbe promised his Chassidim that Elijah the Prophet would be revealed at his seder. On the first night of Passover, the Rebbe's dining room was crammed with Chassidim. The air was electric with anticipation and excitement. The seder progressed, the cup of Elijah was filled and the door opened. What happened next, left the Chassidim speechless. Nothing. Nothing happened. There was no one there. The Chassidim were crushed. After all, the Rebbe had promised them a revelation of Elijah. The Kotsker, his face radiating holy joy, perceived their bitter disappointment and inquired as to what was the problem. They told him. " Fools!" he thundered. "Do you think that Elijah the Prophet comes in through the door? Elijah comes in through the heart."

DAVID: Miriam's Cup is a new ritual for the Passover seder. Its purpose is to honor the role of Miriam the Prophetess in the Exodus and to highlight the contributions of women to Jewish culture, past and present. Like most religions, Judaism developed within a patriarchal society. Men recorded and interpreted religious law and wrote the traditional prayers.

JANE: We are among those Jews having a seder tonight who add this special cup--not a cup of wine but of water.

Someone holds up Miriam's cup.

JAMIE-LEE and JANE: Miriam's cup is filled with water to symbolize Miriam's miraculous well. The well was given by God in honor of Miriam, the prophetess, and nurtured the Israelites throughout their journey in the desert.

[We pass Miriam's cup around the table.]

ELLIE and LOIS: Miriam was Moses' older sister. Both before Moses as a baby was put into the Nile and after the Hebrews left Egyptian bondage, Miriam played a crucial role in Jewish freedom.

LEADER: A Midrash teaches us that a miraculous well accompanied the Hebrews throughout their journey in the desert, providing them with water. This well was given by God to Miriam, the prophetess, to honor her bravery and devotion to the Jewish people.

HANNAH: Both Miriam and her well were spiritual oases in the desert, sources of sustenance and healing.

BOB P.: Her words of comfort gave the Hebrews the faith and confidence to overcome the hardships of the Exodus.

SAM: We fill Miriam's cup with water to credit her role in the survival of our ancestors.

ELLIE: Like Miriam, Jewish women in all generations have been essential for the continuity of our people.

LOIS: As keepers of traditions in the home, women passed down songs and stories, rituals and recipes, from mother to daughter, from generation to generation. Let us each fill the cup of Miriam with water from our own glasses, so that our daughters may continue to draw from the strength and wisdom of our heritage.

LEADER: We place Miriam's cup on our seder table to honor the important role of Jewish women in our tradition and history, whose stories have been too sparingly told.

EVERYONE: "You abound in blessings, God, creator of the universe, Who sustains us with living water. May we, like the children of Israel leaving Egypt, be guarded and nurtured and kept alive in the wilderness, and may You give us wisdom to understand that the journey itself holds the promise of redemption. AMEN." [prayer written by Susan Schnur]

HANNAH holds up a tamborine and shakes it while EVERYONE recites a portion from Exodus chapter 15, verses 20-21: "And Miriam the prophetess, took a timbrel in her hand; and all the women went out after her, with timbrels and with dances. And Miriam sang unto them...

BOB P. "'Sing ye to the Lord, for He is highly exalted; The horse and his rider hath He thrown into the sea.'"

LEADER: As Miriam once led the women of Israel in song and dance to praise God for the miracle of splitting the Red Sea, so we now rejoice and celebrate the freedom of the Jewish people today.

BOB P.: At our seder, we add an orange to the seder plate, as a gesture of solidarity with Jewish gay people and others who are marginalized within the Jewish community. [Bob points to the orange on the seder plate] A few years ago - after seeing how widely the new tradition had spread - Susannah Heschel, its originator, set the record straight about the origins of placing an orange on the seder plate. She had introduced that ritual in her home in the 1980s as a sign of solidarity with lesbians and gay men. The orange, she felt, suggested the fruitfulness the community enjoys when gays and lesbians are accepted into it. She says that she originally added the orange to the seder plate after a man shouted at her that a woman belongs on the bimah (pulpit) as much as an orange on a seder plate.

BOB T.:The orange urges us to include everyone. Miriam's cup reminds us of how important it is for each of us to nurture others. Elijah's cup is for the unfortunate who cannot join us for the seder and who deserve to be part of the new peace when it comes.

LEADER reads the Hebrew and BOB P. and JANE reads the

English:

LEADER: Now we again say the blessing over the wine, and then we will drink the second cup.

EVERYONE: Baruch atah adonai, elohaynu melach ha-olum, bo-ray paree hagoffen. Praised be the king of the universe who makes the fruit of the vine.

HANNAH sings the prayer over the wine in Hebrew:

BEN: Everything about the seder is a symbol. All the things on the table tell part of the story of Passover.

LORENZO points to the bitter herb on the seder plate and says: This is the bitter herb--called "maror." Maror reminds us of the bitter and cruel way the Pharaoh treated the Jewish people when they were slaves in Egypt.

BEN: In Exodus we read that the Egyptians "made their lives bitter with hard labor in mortar and bricks and at all kinds of labor in the fields." (Exodus chapter 1, verse 14)

LEADER: Having been asked 100 times why the charoset isn't usually explained in the Hagadah, Rabbi David Seidenberg wrote the following fascinating answer: "The Hagadah is about telling the story, and it's about order. The story is about how things can transform, and it's a seder because we order the transformations by arranging them from slavery to freedom, or as the Talmud says, "from g'nut/degredation to shevach/praise". The usual order is: slavery, leaving Egypt, entering the land, looking forward to redemption. Okay, so what about the charoset?"

JANE: "The Talmud debates whether or not it's a mitzvah to serve charoset," the Rabbi continued, "but tells the story of the spice-sellers in Jerusalem, yelling out their shop windows 'Spices for the mitsvah!' The essence of the Charoset in the Talmud is not that it should be sweet, but that it should be tart, like apples, and thick like mud. Rashi (but not the Talmud) gives a few interpretations of this: it's a reminder of the (tart) apple trees in Egypt under which Israel made love and gave birth; it's a reminder of the mud and straw (dates/apples and spices) for the bricks they made as slaves."

BOB P. "The word for tartness," the Rabbi goes on to say, "is the same as the words said about the wicked child: 'set his teeth on edge,' and the same words the midrash uses for what happened when Adam and Eve ate from the tree: "their teeth were set on edge". I think charoset might the stuff of what happens when we can't separate out the symbols, when they get stuck together, when the slavery and freedom are mishmashed together. Like the wicked child's picture of the world, there's no separation between worship and enslavement (both are called "Avodah" after all). Like the tree of knowledge, literally the tree of knowing good and evil, i.e., good and evil all mixed together, it represents the way we live our normal lives. It's Jewish realism!"

LEADER: "So we want to transform that place through the seder ritual, but we also bring it along with us, along with the joy of freedom, along with the bitterness of slavery - and that's the Hillel sandwich. So one more lesson of the Hagadah is: don't separate your normal muddled state from the holy and mystical and transformative; even if you're stuck in what is sour, in the mud, add the sweetness. Leave Egypt with all your possessions, the remnants of slavery, the hopes of freedom, and everything in between."

DAVID and BEN say the prayer over the bitter herb in Hebrew:

Leader: We now pass around the bitter herb so that everyone at the table may taste.

LORENZO points to the egg and says: The egg on the seder plate

reminds us that it is spring, a time of rebirth. The Jews left Egypt in

the spring, and it was a time when they were re-born as a people.

reminds us that it is spring, a time of rebirth. The Jews left Egypt in

the spring, and it was a time when they were re-born as a people.

Leader: We now pass hard-boiled eggs around the table.

JAMIE-LEE points to the haroset and says: This is the haroset. It reminds us of the mortar or cement the Jews as slaves were forced to use as they built things for the Pharoah.

BEN points to the lamb shank: The lamb shank reminds us of sacrifices made for God.

LOIS points to the parsley and says: The parsley reminds us also of spring. Tonight we dip it in salt water to remind us of the tears of the Jewish slaves.

LEADER: Earlier, when we dipped the parsley in salt water, and ate it, we were remembering the tears of the slaves.

LEADER: This is our second year placing a bowl of sliced radishes on our Seder table. And we now pass around these radishes, along with a bowl of salt water. Dip but don't eat just yet.

BOB T.: The red color of the radish symbolizes the blood of innocent people that has been spilled.

BEN: The bitter taste represents the hardship that the people of Darfur and on the Chad side of the Sudan-Chad border are facing. The salt water represents the tears being shed by the Sudanese families whose children or parents or brothers and sisters or husbands and wives have been killed. 400,000 people have been killed so far. Everyone, even the Bush government, has called this a genocide. Another 100,000 people in Chad are in immediate danger. A year ago some of us around this table went to Washington to protest the world's inaction. Unfortunately the situation has changed little since then, and may actually be worse.

ELLIE, BOB T., SAM, and LOIS: Of all people, the Jewish people should be ones to respond - we who have suffered genocide within our living memory.

DAVID: Stubbornly, we continue to bear witness to the promise of a Day when all oppression and war shall cease. As it is written:

EVERYONE: None shall hurt, and none shall do harm, in all My holy mountain; For the land shall be as full of the knowledge of God, As the waters cover the sea. (Isaiah 11:19)SAM: And it is also written:

JAMIE-LEE:

It is not for you to complete the task But neither can you ignore it.

LEADER: We now dip the radishes in the salt water and eat. We recite the following prayer:

What shall I ask you for, God? I have everything. I sit here in the comfort of my own home surrounded by loved ones. I sit here celebrating my freedom and security. There is nothing that I lack. Therefore, I ask for only one thing. I ask this not for myself alone; It's for all of the mothers, fathers and children everywhere. Not just in this land, but in all the lands hostile to each other. I would like to ask for peace, tolerance and harmony. Yes, it's peace and freedom I want for all. I vow to do my part to achieve this.(Adapted from the "Shabbat Vehagim," the Reconstructionist Shabbat and Festival prayer bood, Reconstructionist Press)

JANE: Now comes the part of the seder that is very important for Jewish children. It is called "The four questions." The younger child will ask the question and the older child will answer.

Hannah: Why is this Night Different from all Other Nights?Ben: Why is this night different ? Why do we eat such unusual foods as Matzah, the unleavened bread, and Maror, the bitter herbs? Why do we dip green herbs in salt water? Why do we open doors? Why do we hide and then eat the Afikomen? Why? Why? Why? On all other nights we eat all kinds of breads and crackers.

Hannah: Why do we eat only matzah on Pesach ?

Lorenzo: Matzah reminds us that when the Jews left the slavery of Egypt they had no time to bake their bread. They took the raw dough on their journey and baked it in the hot desert sun into hard crackers called matzah.

Hannah: Why do we eat bitter herbs, maror, at our Seder?

BEN: Maror reminds us of the bitter and cruel way the Pharaoh treated the Jewish people when they were slaves in Egypt.

Hannah: Why do we dip our foods twice tonight?

Lorenzo: We dip bitter herbs into Charoset to remind us how hard the Jewish slaves worked in Egypt. The chopped apples and nuts look like the clay used to make the bricks used in building the Pharaoh's buildings. We dip parsley into salt water. The parsley reminds us that spring is here and new life will grow. The salt water reminds us of the tears of the Jewish slaves.

Hannah: Why do we lean on a pillow tonight?

Lorenzo: We lean on a pillow to be comfortable and to remind us that once we were slaves, but now we are free.

LEADER: Below we see one of the four questions in Hebrew. Now Hannah

will sing THE FOUR QUESTIONS.

:

LEADER: We are almost ready to eat the passover meal. First we must hear the end of the Moses story. Then we shout "Dayanu!" Then we sing "Eliyahu Hanavi."

ELLIE: Moses and the people were smart to leave hastily. Pharoah told them they could go, but then he sent his army to chase them.

LORENZO: Moses and the people got to the Red Sea and were trapped against the water. Pharoah's army was close behind.

JAMIE-LEE: Moses took his staff and caused the Red Sea to part. The Hebrews passed through, yet when Pharoah's army began themselves to cross, the sea closed up again.

BEN: I drew this map of the scene when I was 8.

DAVID: The Jewish people, led by Moses, his sister Miriam and brother Aaron, and others, wandered in the desert for many years. Along the way they came to a mountain called Sinai. Moses climbed the peak to speak with God, and brought back the laws we still live by.

HANNAH: The picture below shows Mount Sinai today.

LEADER: Now we sing a song that is at least 1,000 years old. The Hebrew lyrics mean that if He (God) had only brought us out of Egypt it would have been enough. The second verse adds that if He had only given the Torah of Truth, it would have been enough.

Ilu ho-tsi, ho-tsi-o-nu,

Ho-tsi-onu mi-Mitz-ra-yim

Ho-tsi-onu mi-Mitz-ra-yim

Da-ye-nu

CHORUS

Da-da-ye-nu,

Da-da-ye-nu,

Da-da-ye-nu,

Da-ye-nu,

Da-ye-nu,

(repeat)

Ilu na-tan, na-tan-la-nu,

Na-tan-la-nu To-rat e-met,

To-rat e-met na-tan-la-nu,

Da-ye-nu

(repeat)

(CHORUS)

LEADER: Now I will say a line of the poem and then everyone will say the word "dyenu" loudly.

If He had brought us out from Egypt, and had not carried out judgments against them ...DAYENU!If He had carried out judgments against them, and and had not given us all their money.... DAYENU!

If He had given us all their money, and had not split the sea for us ...DAYENU!

If He had split the sea for us, and had not taken us through it on dry land ...DAYENU!

If He had taken us through the sea on dry land, and had not drowned our oppressors in it ...DAYENU!

If He had drowned our oppressors in it, and had not supplied our needs in the desert for forty years ...DAYENU!

If He had supplied our needs in the desert for forty years, and had not fed us the manna ...DAYENU!

If He had fed us the manna, and had not given us the Shabbat ...DAYENU!

If He had given us the Shabbat, and had not brought us before Mount Sinai ...DAYENU!

If He had brought us before Mount Sinai, and had not given us the Torah ...DAYENU!

If He had given us the Torah, and had not brought us into the land of Israel ...DAYENU!

If He had brought us into the land of Israel, and had not built for us the house of the people...DAYENU!

LEADER: Now we sing the song "Eliyahu hanavi."

E-li-ya-hu ha-na-vi,

E-li-ya-hu ha-tish-bi,

E-li-ya-hu E-li-ya-hu,

E-li-ya-hu ha-gil-a-dee.Bim-hay ra v'ya-mey-nu

Ya-vo e-ley-nu

Im Ma-shi-ah ben Da-vid,

Im Ma-shi-ah ben Da-vid.

HANNAH, AL, and DAVID: We will now sing a traditional Hebrew work song. It is sung in two parts. The first part is simply "Zum gali gali." The second part is:

Hechalutz le'man avodah

Avodah le'man hechalutz

There are also some verses we will add as we go along. Listen for them and join us if you can:

1. From the dawn till night does come There's a task for everyone 2. Pioneers work hard on the land, Men and women work hand in hand 3. as they labor all day long, They lift their voice in song 4. Peace shall be for all the world All the world shall be for peace

LEADER reads the Hebrew hymn below:

biglal avot to-shay-yay ba-nom

vi-ta-voh gi-a-la

li-va-nai vi-nai-ham.

ba-ruch atah adonai ga-al Yis-ro-al.

SAM: Now we all read together the English translation.

EVERYONE: For the parents' sake Thou will save the children, yes, and bring redemption to their children's children. Blessed are thou, O Lord, who has redeemed the Jewish people.

BEN, LORENZO AND HANNAH: And now we eat the Passover meal!