I saw the best exposition of a poem in a major motion picture, Rob Epstein & Jeffrey Friedman’s Howl, coming to art theaters starting on the 24th & also, I believe, available thru various video-on-demand services. Howl is also perhaps the only major motion picture I’ve ever seen that is, in both form & function, the close reading of a text. I have never seen a film based on a work of literature that even remotely approached Howl’s devotion to the words on the paper. If you’re a writer, or care about poetry, you are almost certainly going to love this film. Howl was made for you, with intelligence & more than a little cinematic bravery, and it shows. Howl is a wonderful motion picture.

It is a lot harder, however, to imagine Howl appealing to a broad audience. Virtually every word in this film comes directly from the poem itself – maybe one third of its 90 minutes are given over to a pastiche of different readings that start with the film’s first words, James Franco as Ginsberg reading the title and dedication at the Six Gallery in 1955, then launching into a surprisingly soft [and quite effective] presentation of its famous opening words

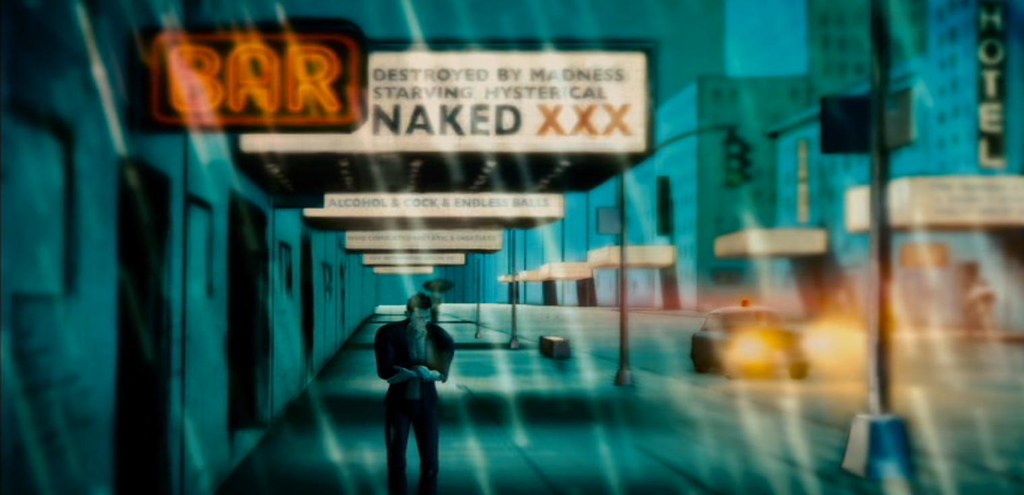

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked

– or from interviews with Ginsberg or the records of the 1957 obscenity trial in San Francisco’s municipal court, Judge Clayton Horn presiding. This makes for a very curious film dynamic – terrific for opening the poem up, maybe not so well suited to holding the attention of Borat fans. Actors portraying Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassidy, Peter Orlovsky & Lawrence Ferlinghetti are on screen a lot, but not one has a single line in this film. The closest we get is Ginsberg reading Cassidy’s “Dear John” letter explaining that the Adonis of Denver really does want to be straight. Other major figures – the other poets at the Six Gallery or other witnesses in defense of the poem, which included Kenneth Rexroth, Mark Linenthal, Walter Van Tilburg Clark, Herbert Blau, Arthur Foff & Vincent McHugh – are missing from the film entirely.

This push-pull between complete erasure & obsessive detailing is a fundamental (albeit strange) dynamic of this project. We learn, for example, which colleges the prosecution witnesses worked at, or hear William Burroughs & Herbert Huncke mentioned by their surnames because they’re in the poem, tho otherwise never present in the picture, Lucien Carr only by his first name for the same reason, yet Shigeyoshi Murau, who was actually arrested & spent the night in jail for selling a copy of the book to the police, is entirely absent. He was the co-defendant. And perhaps most strangely, given that Epstein & Friedman are San Franciscans, or that Ginsberg wrote the poem at Peter Orlovsky’s apartment at 5 Turner Terrace atop Potrero Hill or that the trial was a San Francisco affair, Howl was filmed entirely in New York.

Except for that portion that was done in Thailand. A major component of the film is a series of animations created by a team led by Eric Drooker to illustrate those aspects of the poem that are too abstract (Moloch!) or too literal perhaps in their presentation of matters physical (a child emerging from its mother’s vagina being the most explicit), often as sparkly spirits swoop overhead – these spirits are not so much elements of the poem (unless of course we imagine them as angel-headed hipsters) as they are aspects of forced narrative cohesion. There are some moments where I laughed out loud at animated clichés (my fave is a forest of undulating penises looking ever so much like seaweed), but the animation mostly solves one of the major cinematic challenges of this work – what to look at while listening to a poem.

Those portions of the poem that aren’t presented through animation are read aloud in court or at the Gallery Six event (the literary importance of which is never mentioned) or in snippets as we watch Ginsberg typing away on Turner Terrace. It’s in the animated moments in particular, an extension of Drooker's work in Illuminated Poems, that you realize that we’re not in Hollywood anymore, in spite of the presence of several major actors. These passages let you know that the filmmakers, indeed everyone connected to this project, have decided to be loyal to the poem, not to any cinematic conventions of American cinema. The structure of the film is the structure of the poem. Period.

It’s easy to make caricatures out of the “villains” of the piece, the sputtering prosecuting attorney, played by David Strathairn, the prissy little Quietist who adjuncts at a Catholic college in the burbs or the somewhat more avuncular literature professor from the University of San Francisco – another Catholic school. Both Mary-Louise Parker’s Gail Potter & Jeff Daniel’s David Kirk are shown losing their composure on the stand. Potter can’t fathom why the defense attorney has no questions for her; Kirk gets so tongue-tied it’s impossible to unravel. But it’s worth noting that these were the only witnesses for the prosecution in 1957, and that one of defense attorney Jake Erlich’s strategies was to get more witnesses, more famous witnesses, with better literary credentials. Luther Nichols, the newspaper critic who actually comes across in the film as the smartest reader of the poem, was in fact the book critic for the San Francisco Examiner when it was the flagship of the Hearst empire – he was the equivalent in 1957 of Michael Dirda at the Washington Post or Carole Kellog at the Los Angeles Times today, and soon after left the paper to become an acquisitions editor at Doubleday. So if the prosecution witnesses seem and sound foolish on screen, keep in mind that the film makers could have laid it on much thicker than they did. The filmmaker’s only concession to Jake Ehrlich’s overkill defense strategy – he was dealing with a judge known to assign viewings of The Ten Commandments is misdemeanants – is the choice of John (“the sexiest man alive”) Hamm to play Ehrlich. Dressed in the same 1950s garb he’s made fashionable again in Mad Men, Hamm’s only sign of weakness is to roll his eyes and glower at the sheepish-but-silent Ferlinghetti figure whenever the prosecution quotes a particularly embarrassing passage from the book.

Parker’s testimony is noteworthy in that it’s the only dialog spoken by a woman in the entire movie. And she’s onscreen for less than three minutes. You can just imagine the pitch these filmmakers must have given trying to raise the funds for Howl: we’re going to close read a poem for the entire length of the film, surrounding it with gay men & lawyers. Reese Witherspoon is nowhere in sight.

What we get from this very curious mélange of creative writing & courtroom jousting (with Ginsberg’s own interviews serving mostly as background for the other two threads, and as a mechanism for getting Allen into the tale since he studiously fled to New York & never once attended the trial – we learn about his father, his mother, his arrest in New York & time in the “looney bin” with Carl Solomon, his emerging sense of his own homosexuality) is the poem in its social context. Epstein & Friedman don’t, for example, pay any attention to how Ginsberg’s use of condensation extended a practice he got from Pound but in the framework of a totally different discourse so that phrases conjoined from distinct vocabularies – “hydrogen jukebox” – would become a hallmark of so much American poetry after Howl. Nor are they interested in how the Beats gave us the cultural revolution we know today as the 1960s. What they really want to understand is what this explicit acknowledgment of Ginsberg’s own homosexuality did to him, for him, and for the culture. Howl, in this sense, is as much a part of gay history as it is literary history.

A few years from now – unless the forces of darkness impose a new wave of censorship – Howl, the movie, is going to be the perfect film to show to a group of college undergraduates in an introduction to literature course. It shows – as no film before ever has – how a work of writing sustains interest & focus, and does a decent job showing how such a work comes into being. It would work well also with a graduate course, reading the text in the Harper Perennial facsimile edition so that students can look at all the revision in this “spontaneous” outpouring, asking why, for example, starving mystical naked became starving hysterical naked & the vast consequences for tone & vision that single substitution set in motion.

Now if only somebody will do the same for Allen Ginsberg’s best work & not just his most famous, for example “Wichita Vortex Sutra” or even “Wales Visitation.”