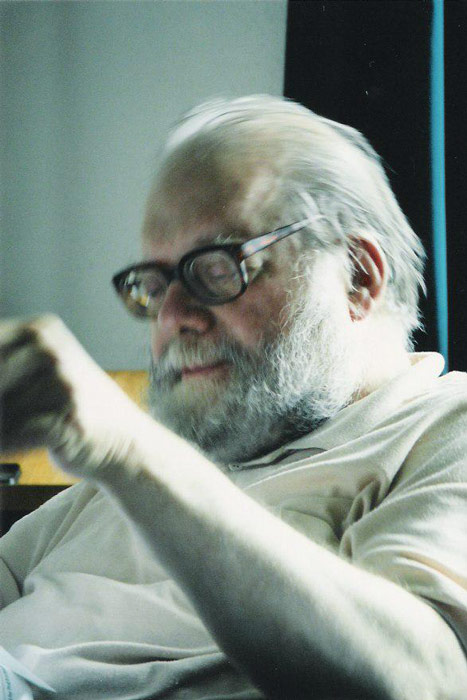

Philip Hobsbaum

I’m just far enough removed from reading John Ashbery’s Other Traditions for it to begin to resonate in my thinking at odd moments, for example while I take my shower in the morning, in that new & synthetic way that happens once a work starts to operate as memory rather than as present fact. The thought that has been haunting me, if that’s the operable word, is that Ashbery is trying in that book to articulate an avant-garde tradition for American poetry that is not, by definition, the Pound-Williams tradition. When I stop & think about the Allen anthology & the enormous influence The New American Poetry: 1945-1960 had on writing in the U.S. (& elsewhere), it does seem that Ashbery is one of at most five of that volume’s 44 writers operating outside of the larger Pound-Williams framework, the other four all being writers from the West Coast: Brother Antoninus (William Everson), James Broughton, Helen Adam, & Jack Spicer.

That observation instantly provokes a whole chain of caveats. First, Ashbery does acknowledge “some of” Williams more than once in Other Traditions, & I think he’s being relatively straightforward in doing so. Second, there have always been an active, successful American avant-garde outside of the Pound-Williams legacy. One can only imagine – tho the thought of it is rather amusing – what Gertrude Stein might have said had she been asked about her relationship to Williams & Pound. Third, and far more problematic, is the question of Eliot, beloved by Pound, resented by Williams, whose work & influence plays out quite differently in the U.S. & U.K. This in turn triggers another free association, a most useful note I read yesterday on Jeffrey Side’s blog, linking Seamus Heaney to the late Philip Hobsbaum’s anti-modernism, which was also, in the same moment, an anti-American &

anti-speech-based poetics aesthetic. Side quotes Hobsbaum to the effect that “damage” was done in the 1930s to British writing through the influence specifically of Eliot & Pound. Thinking of Eliot as the emissary of Whitman & Williams in the

This in turn gives rise to some other thoughts. One is that the

One might say – and reading Ashbery here can be seen as one step in that argument – that the relatively monolithic moment of the School of Quietude was only a brief blip in the history of American poetry, indeed that same 15-year span covered by the Allen anthology, and that it had been much more diverse & polyvocalic both before 1945 & in the decades since 1960. If not Ashbery’s argument, per se, then at least Ashbery’s implication would seem to be that one could trace within that broader, more diverse reading an alternative if not overtly avant-garde lineage quite apart from Williams & Pound and their joint emphasis on the role of the line in poetry.

The elimination of that emphasis, the legacy of imagism (& beyond that, of Dickinson & Whitman, the two 19th century poets whose formal innovations invariably engage the line), opens up writing not only to an increased influence from the likes, say, of Stevens & Crane (the two poets most central to Creeley, in fact, once you get past Williams & Olson), but to all manner of loners, writers whose principle relationship to a tradition is that it seems to have made them feel uneasy.

This is where, to my thinking, the resurrection of the Objectivists in the 1960s becomes a fascinating social question. Unquestionably, the Objectivists were – as they themselves recognized – the missing link between Pound & Williams and the New Americans. But they also were not so dramatically removed from certain independent poets, especially around

However, Objectivism in the 1960s, in its third phase¹, was quite different from Objectivism in its heroic first period, when these Marxist modernists were in stark contrast not only with other modernists because of their politics, but also other Marxists because of their modernist aesthetics. Indeed, if one looks at a representative issue of San Francisco Review, a journal funded by Oppen’s sister, June Degnan, in part to promote her brother’s work², one notes a careful blend of New Americans, older modernists, & even Quietists, but specifically those who favored a “plain spoken” & “direct” style that jibed well with Oppen’s neo-imagist mode: Jack Anderson, Diane Wakoski, Judson Jerome, William Stafford, Patricia Goedicke, Curtis Zahn, Bern Porter, Thomas McGrath, James Schevill, Lew Welch, Walter Lowenfels, Lewis Turco, George Hitchcock, George Abbe, Cynthia Ozick, and of course Oppen himself. Eleven Oppen poems were published in Poetry – this was during Henry Rago’s editorial reign – while

I’ve written before of how the Berkeley Renaissance – the work done by Robert Duncan, Robin Blaser & Jack Spicer, prior to, say, 1952 – can be read as an instance of modernism that looks to Yeats, not Pound, as its figure for the modernist venture. (And similarly, I’ve written of how one can read someone like the Canadian Louis Dudek as an instance of how such poetry might have evolved had it not run headfirst into the 6’9” presence of one Charles Olson.) If one looks also at the work of those other West Coast poets operating outside of the Pound- Williams paradigm in the Allen anthology – Everson, Broughton & Adams – you can see vestiges of it there as well. Ashbery’s model, which he consciously pluralizes as Other Traditions, is different primarily in that it is not western, but the vein he is tapping – in Laura Riding, John Wheelwright & David Schubert in particular – is not particularly at odds with these western neo-romantics, nor with some others outside the Allen anthology, like the two Kenneths, Rexroth & Patchen. Plus of course Everson's model, Robinson Jeffers. It also makes it possible – easier, certainly – to see all the ways in which some others in the Allen collection – Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Philip Lamantia, Gregory Corso, Edward Field, Madeline Gleason – can be read as easily outside of the larger paradigm as they can within it.

Ashbery’s gesture thus is a complicating one, casting new shadows because it reveals new depths. And this is what I think about, standing there in the shower.

¹ Phase one being 1930s period when the literary phenomenon – it’s not quite accurate to call it a movement – first coalesced & its major practitioners were all active publishing; phase two being the 1940s & much of the ‘50s, when many of the Objectivists had stopped publishing &, in some cases, stopped writing altogether.

² Oppen’s first two books with New Directions, The Materials & This in Which, were co-published by San Francisco Review, which is to say that June Degnan funded them & James Laughlin did the work.