Margaret Brown’s Be Here to Love Me: A Film about Townes Van Zandt has been having its theatrical release this past month in

Booze. That & quite probably a psychiatric disorder that was badly handled back in the days of electroshock-as-therapy, plus, just here & there, some additional fun with heroin, guns & jumping off of four storey buildings in order see what it felt like. As recounted through film clips & the remembrances of friends and colleagues, Van Zandt was high maintenance even when he was in school but the addition of addictions, primarily to alcohol, gave everything a toxic edge from which no one in his sphere could ever quite escape. Even his death, which I’ve seen described as due to heart failure after hip surgery, is more than a little tinged with booze. Steve Shelley, the drummer of Sonic Youth, wanted to give Van Zandt a more serious recording experience than he’d had before but Van Zandt showed up at the studio in

In his biography of Frank O’Hara, Brad Gooch suggests that the poet might have survived his run-in with the dune buggy had only his internal organs not been so compromised by a lifetime of alcohol. One can only wonder what might have happened had Van Zandt stayed in the hospital, but the deeper reality was that the singer spent over 30 years abusing his body in every way possible – the number of references to glue sniffing in his prep school yearbook are eyebrow raising, especially for the class of ’62.

The film is free form and more impressionistic than historical in tone. It proceeds chronologically, but with such a light touch you’re almost not aware of it. We see Townes interviewed outside the trailer that was his home in Austin while a friend fires a rifle repeatedly at unseen targets – we see him explain, in a painfully shy fashion, to a TV host how he dreamt he was performing If I Needed You & then woke up & wrote down the words & tune. We get to watch Guy Clark drink tequila & explain how he always felt that Townes was putting moves on his wife (while she denies this). We see Van Zandt’s second wife Cindy as a fresh-faced hippy barely out of her teens & then, many years later, looking as though she’s lived a hard life indeed. Townes’ oldest son explains how angry he is at his father’s addictions & Steve Earle recount a story of watching Townes play Russian roulette with a loaded pistol, pulling the trigger next to his forehead three times before setting the weapon down. We meet a friend from his stay in the psychiatric ward, explaining the profound impact of electroshock on personalities and lives.

We hear multiple people explain that they thought that Townes was the best song writer they’d ever seen/heard/met. But at no point in Brown’s film does anyone attempt the kind of close reading that one gets, routinely even, with Dylanologists. From my perspective, that’s the weakest point of the picture. We get to hear the songs, sometimes by Townes, other times by Lyle Lovett, Emmylou Harris, Willie Nelson & Merle Haggard – we even learn a little about how they feel about them (Harris and Townes’ first wife both say that If I Needed You was written “for” them, an explanation at odds with Van Zandt’s own.) If you look at the actual lyrics –

If I needed you

would you come to me,

would you come to me,

and ease my pain?

If you needed me

I would come to you

I'd swim the seas

for to ease your pain

In the night forlorn

the morning's born

and the morning shines

with the lights of love

You will miss sunrise

if you close your eyes

that would break

my heart in two

The lady's with me now

since I showed her how

to lay her lily

hand in mine

Loop and Lil agree

she's a sight to see

and a treasure for

the poor to find

– they’re quite simple. While they tend toward certain patterns, they’re not at all rigid in their structure. Thus the ABBC format of the first quatrain is not repeated in the second, which is BABC. The next two stanzas both contain two quatrains, but now the rhyme scheme has become more regularized – AABC. Only in the final stanza do we find a second rhyme – the last line of each quatrain. What this scheme really sets up, tho, is a critical pause that occurs at the end of the third line in each quatrain. Listening to recordings of either Van Zandt or Harris, it often sounds as if two short lines lead to a longer third, e.g., to lay her lily hand in mine, and that ambiguity – to my ear at least – is the key to this song’s measure.

Also worth noting are the number of syllables per line here – a number that in the song itself means that shorter lines possess words that will extend over the music. Each stanza contains six five-syllable lines, and two shorter ones. It’s worth noting where in the three stanzas these condensed lines fall, again in a pattern that is both intentional & not systematic.

Above all else, this is a text dominated by one-syllable words, a device that harkens back to poets like Larry Eigner & Lew Welch. In these 24 lines, just ten words have two syllables and none have more. The only moment of difficulty, to even call it that, is the reference to two persons,

A final – and my favorite – touch is the use of the word or syllable for, which occurs exactly once in each stanza, always at a critical point. That’s a tiny detail, but it says a lot about Van Zandt’s formal imagination, which is hardly as haphazard as we’ve come to expect from popular song. Did this come to him in a dream as he claimed? We should all be so lucky.

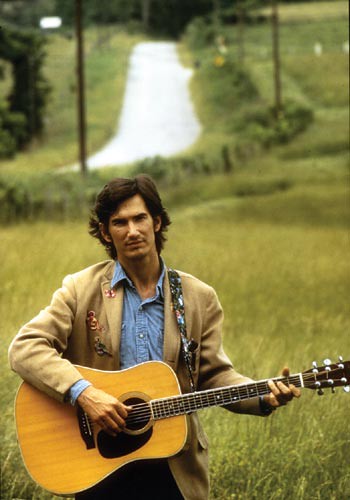

If Brown’s film misses an opportunity to seriously explore the construction of his works, it does go a long way to humanize Van Zandt. People went out of their way forever to accommodate his quirks & patent disabilities not just because he could vary rhyme schemes with such elegance. He had a likeable puppy-dog air that must have brought out the Protector in a lot of people – that’s not a quality you see in the likes of a Dylan or Neil Young, but they’re comfortable with being in charge in ways Van Zandt never was.

Watching this film made me wonder what a comparable project with regards to Jack Spicer might feel like. Hardly anything is more predictable – or more painful to watch – than a person in the last stages of alcoholism as they crash & burn. Be Here to Love Me ends with performances by Guy Clark & Lyle Lovett at Van Zandt’s funeral, poorly shot home-movie footage that is shown running on a TV set within the screen (a device Brown uses often). “I’m not sure I can get through this,”