A week ago Monday, I noted what I took to be a curious claim in the Poetry Foundation’s Poetry in America study, that “The Poetry Foundation’s primary concern is with the reading and listening audiences for poetry.” It is, in fact, the closest thing this report has to a topic sentence, and it appears toward the end of the discussion of key findings. The entire paragraph is worth quoting:

The Poetry Foundation’s primary concern is with the reading and listening audiences for poetry. However, stakeholders and participants in the qualitative research phase of this project felt it was important to collect information about people’s experiences writing poetry. We asked all participants about their experiences writing poetry as adults, and we asked those who wrote poetry about their experiences performing their own poetry. Their responses are summarized in Table 8. Thirty-six percent of all readers have written poetry as adults. Poetry users are significantly more likely to write poetry (45 percent) than are non-users, fewer than 1 percent of whom have written poetry as adults. Just over one-quarter of the adults who have written poetry (27 percent) have performed their own poetry in public.

This assertion explains a good deal of the 113-page report: why it asked certain questions and not others. But those relatively high percentages of poetry writers and performers suggest that the Poetry Foundation’s primary – and never fully articulated – assumption may in fact be false. With it, many of the premises surrounding not only this study, but its sponsors, the editors and publishers of Poetry magazine, dissolve pretty quickly. Indeed, it accounts for a good deal of the pathology at the heart of the Poetry magazine project.

The focus of Poetry in America is neither poetry, nor poets, but a third category it identifies as “poetry users,” a group it breaks into further subsections of readers & listeners & “former poetry users.” As the introduction states,

Poetry in

1) What are the characteristics of poetry’s current audience?

2) What factors are associated with people’s ongoing participation with poetry?

3) What are people’s perceptions of poetry, poets and poetry readers?

4) What hinders those people without a strong interest in poetry from becoming more engaged with this art form?

5) What steps might be taken to broaden the audience for poetry in the

But “participation with poetry” only incidentally means actually writing it. This study isn’t about poetry, but its “current audience.” The chapter headings set forth the primary research concerns:

* Demographic characteristics

* Understanding how people spend their time

* General reading habits

* Early experiences with poetry

* Later experiences with poetry

* Intensity of engagement with poetry

* Perceptions of poetry, poets and poetry readers

* Benefits and barriers

* Incidental exposure to poetry

* Opportunities for exposure to poetry

* Favorite and long-remembered poems

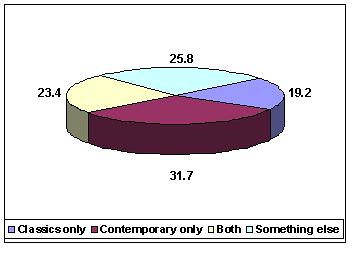

Thus when, in the chapter on later experiences with poetry, the researchers ask what kinds of poetry “users” currently read, the categories they offer are contemporary and classic, as tho they were brands of Coke. Interestingly, contemporary proves more popular than classic, as the graph below sketches out, giving possible responses and the percentages assigned to each. Some 31.7 percent read contemporary poetry, which might be Billy Collins & might be Geof Huth & might be Kari Edwards – we have no way of telling further, to just 19.2 percent who only read classic.

In fact, these numbers weren’t those given by the raw data. The

Over a third of current poetry users define the type of poetry that they read as “something else.” We asked respondents to specify what they meant by “something else.” Their responses were reviewed by project staff and the data were coded for those responses that appeared most frequently. Many of their responses did not fit into any category; however, there were four that repeatedly came up in the pool of ‘other’ responses: personal, friend’s or relatives’ poetry; modern poetry; children’s poetry; and inspirational poetry. While modern poetry could clearly be classified as contemporary poetry, the other categories and verbatim responses did not fit into either designation – classic or contemporary.

The question of how might Poetry – as distinct from “poetry” – serve “users” better isn’t one ultimately about writing, but about distribution. Nor is it just any model of distribution that is being contemplated. The report’s final section – “What Steps Might be Taken to Broaden the Audience for Poetry in the

*

* Develop programs for teachers

* Help libraries and book clubs foster participation

* Increase poetry’s presence on the internet

* Create new opportunities for incidental exposure

* Challenge people’s perceptions

* Evaluate all programs

The first three suggestions are all deeply institutional. “Develop programs” is the sort of phrase that neocons twitch at whenever they hear the words coming from the mouths of the likes of Teddy Kennedy or John Kerry. And libraries, as at least one publisher I know likes to complain, are government institutions that, by concentrating books for sharing on a serial basis, theoretically may undercut the sales of publishers.¹ Underlying the first three suggestions, and just under the surface in most of the others, is the report’s ultimate presumption:

Poetry is an expert discourse written by professionals, distributed to, and read by a larger group of non-specialists.

It seems like a reasonable premise if the question you are asking is to reaching an audience whose list of favorite poems – from a survey that began with over1,000 people – turns up just nine poems that were listed by five or more respondents each and these were (in this order):

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner

Written in 1936 by a 14-year-old, Mary Stevenson’s “Footprints,” a staple of inspirational verse, is the most recent text on the list.

Similarly, the report’s recommendation to increase poetry’s presence on the internet, reads tres retro:

Adult readers have access to the Internet at rates higher than what is seen in the general population. Currently, few poetry users turn to the Internet to access poetry or to find information about poetry events. However, as the Internet evolves, ever increasing numbers of people are using it, and the Internet is increasingly becoming the source for all kinds of information. There is no reason why poetry should be the exception. Websites devoted exclusively to poetry will most likely be visited by people who already are involved with poetry. But, even if relatively few poetry users visit poetry websites, poems are shared. Surprisingly high percentages of people who do not identify as poetry readers were sent poems via email or because someone copied them out for them. The Internet can deepen participation for current poetry users who will use it to search for poetry, and their social networks will broaden participation.

The use of the Internet for poetry has broader applications beyond developing websites devoted to poetry. Poetry is already part of solemn and special occasions. Placing poetry at sites devoted to these kinds of private ceremonies can help make people more aware of poetry’s role in commemorating important events.

These paragraphs could have been written a decade ago. And while their overarching generalities keep this passage from being wrong, as such, the nod that “surprisingly high percentages of people who do not identify as readers were sent poems via email…” returns us again to a world in which Caroline Kennedy’s anthologies of poetry, and those of Garrison Keillor, seem perfectly appropriate fare.

As a one-time contributor to Poetry, I know that this doesn’t touch my world in any meaningful way. But here’s my question: does it touch the world of Christian Wiman and the current generation of old/new formalists he represents? If it does, how very sad for him. If it doesn’t, one wonders just how much money the Poetry Foundation sunk into this project. One can imagine the New York trade publishers funding this sort of research, because it really has more to do with their use of poetry as coffee table and Christmas gift-ware, what to give to that sensitive but strange niece, that sort of thing. But as a study of the sociology of poetry, what is most remarkable is just how far it misses the mark.

More than anything, this study reminds me of the one time I found myself passing the offices of Hallmark in the

¹ This is, I think, nonsense, but the point of view is worth acknowledging.