I respond positively to ambitious work. Not every twenty-something who sets out to change the world into his or her vision manages to make much headway, but over time, watching the evolution of a Barrett Watten, a Kathy Acker, a Robert Grenier, a Judy Grahn or a Clark Coolidge as they set out to do so is a tremendous way to spend a life in writing. I find Charles Olson’s earnestness winning, although I know others who find (or, especially, found, during his own day) it overbearing & more than a little obnoxious. For my money, that’s just the price of admission & a very small one to pay to gain all the riches you can find there. Ditto Ginsberg or Duncan. Or Jack Spicer, who intended to change the world, but didn’t plan on informing anybody outside of a small cabal of drinking pals at Gino & Carlo’s.

One of my great complaints about younger poets over the past 20 years has been that far too few are trying to do as much as they might. The very absence of literary group formations is a sign of same, given that one of the primary consequences of any literary movement is that it gets all of its participants’ adrenaline running, so that everyone is performing at the peak of their potential, precisely because they feel challenged to go beyond their comfort zones. If you had told me, in 1969, that by 1974 I would be writing something like Ketjak, in which sentences repeat obsessively & the content of one deliberately avoids flowing smoothly into the content of the next – and that it would be prose – I would have thought you were nuts. But, surrounded as I was in San Francisco by the likes of Kit Robinson’s Dolch Stanzas, Rae Armantrout’s crystalline structures of lyric, Carla Harryman’s theatrical prose, David Bromige’s deep dive into syntax, Bob Perelman’s talk series, Steve Benson’s improvisational poets – they terrified me, because I knew I could never do that, let alone do it with the brilliance & grace that appears so effortless to Benson – not to mention Acker, Watten or Grenier, writing Ketjak was the very least I could do in 1974 – it was (still is) a work filled with caution, because that’s my nature.

So when I see attempts to go further – whether it’s the prose of a Taylor Brady or even a wrongheaded coterie of iconoclasts like the Apex of the M moment circa 1990, I’m predisposed to approve, because I can sense the reach that’s being made. And reach is at least 80 percent of what it takes – quality being the other 20 (and the iceberg lurking to many a Titanic effort). In fact, this is why the well polished variations of important work that come along a generation after whatever raw innovation might take place never is nearly as significant as the groundbreaking work itself. It’s not about making it perfect, but making it new, which is to say equal to the world we live in, which is never the same one we inhabited last week. Do it well enough & you get to be Ted Berrigan or John Ashbery. Do it perfectly 20 years later & there just might be a rural state college out there for you somewhere.

One new book that sets off all of my sensors – it is flagrant & cheerful with its ambition, which strikes me as enormous – is Jessica Smith’s Organic Furniture Cellar: Works on Paper 2002 – 2004. OFC might not be the best written book of 2006, but it almost certainly is the one that wants to do the most. And that means that it just may be the most important book this year as well.

Put simply, Smith is making the argument here for what she call plastic poetics, a concept she means more or less literally. I call it an argument because, in order to read Smith’s work intelligently – perhaps even sympathetically – she wants you to rethink your ideas of the role of space in the text itself. This she accomplishes by means of a nine-page introduction – the most serious theoretical discussion I’ve seen at the front of a book of poetry in some time. You can find what I take to be a preliminary draft of this document tucked away on one of Smith’s several websites here in a PDF format. Both versions are worth reading. In each, Smith begins by describing the experience of viewing a work by Japanese Architect Arakawa and his partner, poet Madeline Gins, a “house” – Smith uses the scare quotes –

that consists of 2400 square feet of cloth lying low to the ground. Entering the house, the visitors find that in order to do anything—move, sit on furniture, cook—they must constantly lift the fabric “roof” of the house high enough over their heads to slither through the space. One of them observes, “Rooms form depending on how we move. If I bend down, I nearly lose the room.” This interdependency of agent and architecture is characteristic of Arakawa’s work, which consistently explores the theoretical problems of being a body in space. Questions of how one occupies space, how one affects and is affected by

architecture, move to the fore. A building is no longer a dwelling-space, but a site of reciprocal becoming.

This is not unlike the process of viewing sculpture – I recall Barney Newman’s definition of same as “what you bump into when stepping back to view a painting” – an analogy Smith likewise notes. Indeed, the contrast Smith is after is that distinction between painting & sculpture that alleges¹ one views a painting all at once, while having to then walk around a sculpture. The poetry Smith is after is far closer to sculpture, but it is not simply or only that:

Historically, “plastic poetry” has been conflated with terms like “concrete poetry,” “calligrams,” and “visual poetry.” The term most often denotes poetry that has simply been made of materials other than paper, like the poem inscribed in concrete on bp nichol lane in Toronto, or the sculptural poems of Ian Hamilton Finlay. However, the material three-dimensionality of poems should not automatically grant them the status of plastic poetry. This term must be reserved for works that disrupt the reader’s virtual field in the same way that architecture and sculpture disrupt an active person’s real, physical field. A plastic poem must change the reading space in such a way that the one who reads is forced to make amends for new structures in his or her virtual path. The words on a page must be plastic in virtual space as architecture and sculpture are plastic in real space. In other words, plastic arts disrupt an agent’s space: to have plastic poetry we must disrupt the reader’s space. I will argue that this rupture does not stem from, as in the ordinary plastic arts, a real physical occupation of space, but rather from the disruption of the virtual space that one moves through when reading a poem.

(Both of the above quotes come from the draft version.)

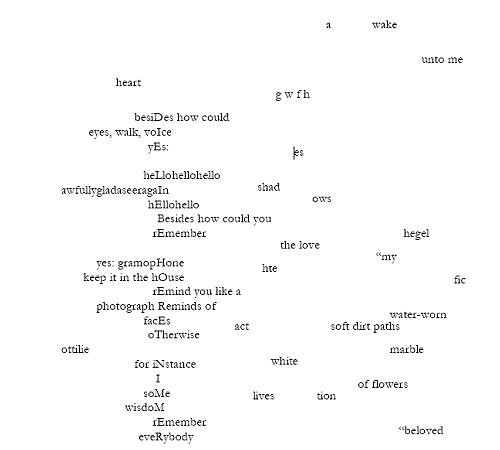

A skeptic might argue – check out the comments stream in a day or so – that it’s a weak poet who puts a theoretical defense in advance of the work itself. However, the precedents of Wordsworth & Coleridge in Lyrical Ballads, of Whitman, of Baudelaire all demonstrate that this is hardly the case. Rather, critically savvy authors have always felt the responsibility to prepare the audience for what’s to come. Here is, crudely reproduced from a screen capture, an example of what Smith is getting at, an excerpt from “Hades” in OFC’s “Exile” section:

Whether one focuses on this poetry’s roots in the work of nichol & Finlay, as in the excerpts I quoted above, or in Apollinaire’s Calligrammes & Steve McCaffery’s legendary Carnival, as the intro to the book does, Smith’s concerns & roots both strike me as quite clear. It’s really about renegotiating the reader’s role in determining not just the meaning of the poem (something readers have done forever) but even the path of the poem. Meaning here doesn’t form & wait for the reading mind, but rather offers clusters of potential, some more straightforward than others, some more subtle than others. The reader’s role is not only to determine what is going on in any cluster, but the order & relationship between them as well. For example, what is the relation of the word “hegel,” presumably the philosopher to the text on its left? The capitalized letters forming a spine running vertically through the lefthand clusters appear, at first glance, to be some sort of acrostic, but if so, then they must anagrams as well. If not, then their

motivation is spatial & not content-driven. For me, the most powerful sequence in this excerpt runs along “water-worn / soft dirt paths // white / marble / of flowers,” tho I know I’m putting those lines together – even putting the left most word “white” ahead of “marble” even tho it’s down a line. Whereas the lefthand clusters to my ear sound like a reiterated, virtually stammered phone conversation, maybe a generation removed from the overhead diction of Eliot’s “Waste Land,” (hurry up please it’s time) but hardly on a different order. And I suspect that anyone’s negotiation will be, if not similar to my own, at least of a similar order of decision-making, of taking responsibility for pulling texts into context, assigning or even infusing meaning.

Ultimately, I think the question of whether or not a text like this works comes down to your sensibility as to how much responsibility you want the author to hold onto, how much you yourself are willing to take on, and whether that matters. There is, in any text (even this one) invariably a one-sided relationship – only the author gets to determine which words appear on the page. You can play with this a lot (and I have over the decades, ranging from the disjunctions between sentences of Ketjak and Tjanting to the intrusive-to-the-edge-of-sadism questioning in Sunset Debris), but my own sense is that I want – indeed, I want to argue that I think readers in general want – the author to err on the side of control.

Which, at this point at least, is the difference I see between OFC & a project like Carnival – if you look at any detail of McCaffery’s, the individual words may not demonstrate more control (they seem to alternate between found materials & pure lettrism), but visually they do:

In a way, Smith’s text is far more readerly – it’s all about the text, ultimately – but it places much more of the responsibility for meaning onto the reader than does McCaffery, even if his sense here of “meaning” isn’t necessarily linguistic.

Overall, my sense of Organic Furniture Cellar is that it isn’t (yet anyway) the revolution that Smith wants to televise, tho her aim here is sharp & she’s already marshaling some of the heaviest weaponry available. But I don’t think you can disrupt reader’s expectations without more control of them than she wants to have here. So I’m interested to see just what Jessica Smith will be coming up with next.

¹ Smith acknowledges that the allegation is false. Even the flattest all-over painting is, ultimately, read in time – indeed there are studies of eye movements around visual fields that are widely used these days in setting up the allocation of information in display ads. In general, the eye in a “portrait” starts above center slightly, the curls down & to the left, then up to the upper left corner & then down across the page toward the lower right, before pulling back and taking in the whole. The portion of the page that is least likely to be closely scrutinized is the lower left corner – a good place to put the mouse type you don’t want consumers to read too closely.