I make use of a lot of bots, automated web tools and searches that bring me things in which I might be interested. For example, a good percentage of the various overseas web stories about poetry I sometimes link to here come from a daily search of all news items tracked by Google. Once you peel off the clichéd pieces that seem to pockmark the world’s media – Local Author’s Work Accepted for New Anthology (almost invariably one of the vanity press publications that Gary Sullivan was targeting when he first invented flarf) – and the usual gaggle of book reviews (it is startling just how few newspapers bother to get decent writers for their reviews of poetry), a significant portion of what remains will give you a perspective on the world of poetry you might not otherwise come up with on your own.

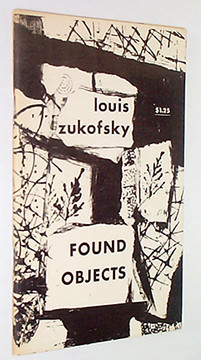

Likewise I have standing “keyword” searches on eBay & elsewhere for work by writers & musicians in whom I have an interest. It was in that connection a couple of weeks back that I came across a Louis Zukofsky item that I had never before seen firsthand, and at a price that was notably lower than any of the copies listed as available on Abebooks.com. The item, Zukofsky’s Found Objects, is a chapbook issued in 1962 by H.B. Chapin as Blue Grass no. 3 from

The subtitle of the book, 1962-1926, offers a sense of its organization, reverse chronological order, something I think I’ve seen elsewhere only in Early Days Yet, the collected poems of Allen Curnow, the late (& definitely great) New Zealand poet. It’s a slim volume, just 44 pages, only eleven poems, tho the poems include “Mantis” and “Poem Beginning ‘The’” among them. At the time, only one of the poems here, “The Ways,” had not yet appeared in any book. The “book of origin” for every other poem here is duly noted at the end of each text. (But, in the Johns Hopkins edition of Zukofsky’s Collected Short Poetry, Found Objects is not credited as the source book for this poem, but rather After I’s.) Typed rather than typeset, Found Objects reflects a particular moment in Zukofsky’s career, the instant before he becomes – after four decades of work – widely read & influential.

Like all of the Objectivists, Zukofsky went through a “quiet period,” going ten years between books between 1946 and 1956. This hiatus echoes – it’s what a financial analyst would characterize as a “trailing indicator” – the eight year break Zukofsky took from the composition of “A” between 1940 and ’48. Other Objectivists, including Carl Rakosi, George Oppen & Basil Bunting, all went through even deeper periods of silence & non-writing. At the time Zukofsky “went dark” publishing, he had had just three real books, his curious critical tome Le Style Apollinaire; 55 Poems, published in 1941, a good 13 years editing the Objectivist issue of Poetry, and Anew, published in 1946.

The seeds of Zukofsky’s eventual success lay in some typed pages of his poetry – this was literally pre-Xerox – that Robert Duncan took with him to

Zukofsky’s two books in the 1940s, 55 Poems, published in 1941, and Anew, published in ’46, had at least been published by one of the more prolific publishers of poetry in the

Zukofsky’s first book with the press went through several bindings, if not multiple print runs, and thus probably got more visibility and distribution than Some Time received 15 years later. Indeed, Barely and Widely, Zukofsky’s next collection, printed in 1958, probably his best known volume prior to the publication of his collected short poems under the title All and the emerging publication of “A,” was functionally self-published – the publisher is listed as Celia Zukofsky – again with an entire press run of just 300 copies.

If Zukofsky couldn’t get his poetry to stay in print, he could at least recycle poems in chapbooks to keep his work in front of readers. In 1962, two years before Found Objects, Celia edited a collection called 16 Once Published, containing works from Anew, Some Time, 55 Poems & Barely and Widely, published by the Scottish poet Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn press. It wasn’t until 1965, when “A” 1-12, which had been initially done in a limited edition by Black Mountain fellow traveler Cid Corman in 1959, was reprinted in the U.K., and then Denise Levertov (again a friend of Creeley & especially Duncan) brought out All in two volumes from Norton, that Zukofsky’s poetry finally became widely available (if barely understood).

Found Objects needs to be read in the context of this history, and its simple production values suggests that this volume had a limited distribution, at best. Zukofsky himself, tho, who once proposed a “scientific” definition of poetry, would be the first to disagree. His introduction to Found Objects reads as follows:

With the years the personal prescriptions for one’s work recede, thankfully, before an interest that nature as creator had more of a hand in it than one was aware. The work then owns perhaps something of the look of found objects in late exhibits – which strange themselves as it were, one object near another – roots that have become sculpture, wood that appears talisman, and so on: charms, amulets maybe, but never really such things since the struggles so to speak that made them do not seem to have been human trials and evils – they appear entirely natural. Their chronology is of interest only to those who analyse carbon fractions etc., who love historicity – and since they too, considering nature as creator, are no doubt right in their curiosity – and one has never wished to offend anyone – the dates of composition of the poems in this book and their out-of-print provenance are for them, not for the poets.

¹ Decker’s press had a tragic history. After sinking an initial investment into the press, Decker and his sister Dorothy were able to publish books at first using the revenues from their earlier books, in part by continuing to live with their parents. By the end of World War 2, however, authors were being asked to help subsidize their volumes by buying in advance as much as half of the print runs. Decker eventually sold the press to one of his authors, E.H. Tax, staying on as an employee. A year later, however, Tax discovered irregularities in the books & dismissed Decker, who then left town with his parents, leaving Dorothy to work with Tax. In 1950, however, she shot & killed Tax before committing suicide.