In addition to a wonderful tribute to Barbara Guest by Peter Gizzi, and a rather puffier one for Stanley Kunitz by Michael Ryan & Gregory Orr, the fall issue of American Poet: The Journal of the Academy of American Poets, departs from its usual presentation of poetry as a genteel affair (an essay by Albert Goldbarth, Paul Muldoon close reading Elizabeth Bishop, a “manuscript study” presentation of a handwritten text by John Berryman, a selection of “poems from recent releases” that includes Mark Levine, Sandra M. Gilbert, Seamus Heaney, Carl Phillips & Floyd Skloot), to offer up three “emerging poets,” younger writers who have not yet had a big book out, introduced by a sponsoring poet. Sherman Alexie presents S.G. Frazier, Rodney Jones presents Phebus Etienne & Rae Armantrout presents Joseph Massey.

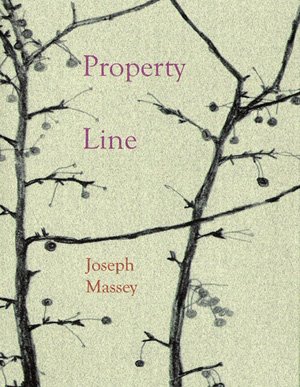

Some family responsibilities kept me from getting to Massey’s reading in Philadelphia a week or two ago, so I was pleased to see him featured here, partly because I’m pleased to see that Armantrout shares my own enthusiasm for his work. The feature includes three poems of Massey’s & one of Armantrout’s. Massey’s poems all come from Property Line, a chapbook from Jess Mynes’ Fewer and Further Press of

Hill’s red

tethered

edge –

berries

that numbed

your tongue

It was the sound of the poem that carried me through it the first time I read it (in the journal before the book, in fact), all those parallel ĕ sounds & that almost subterranean d. Yet a few days later, what lingers more is that one word that semantically stands ajar, slightly out of line with the rest of this otherwise impeccably realist depiction: tethered. In what way (or ways) might a hill be tethered? When I first read the poem, I know that my mind substituted at least the meaning of the word deckled – as in irregular, notched, almost fractal – for tethered. But that’s my mind, and I’m savvy enough about the inner workings of the parsimony principle to know that the reader will supplement whatever details create, for him or her, the simplest, neatest explication. Beyond which, of course, there is an echo of weathered. But that’s not it either. Literally tethered means tied down, a meaning I can’t fit quite with the presence of a bush or a sense of a hill’s horizon. And it’s that not fitting, that imprecision in a work that seems to be exactly a monument to the precise, that gives this poem its depth over time.