Donald Hall & Liam Rector were musing about whether or not the “boomer generation” had any “iconic poems” to call their own. It’s an interesting enough question, although the definitions of all these terms are, I think, more than a little suspect.

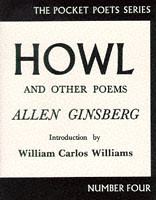

What exactly, for example, is an iconic poem? Is it a text that is not only universally recognized by everyone in the next (and following) generations as a watershed work, a defining moment for the age? Something known as a synecdoche for poetry itself by nonpoets? If so, then the iconic poems of Mr. Hall’s generation (indeed of the latter half of the 20th century) are exactly one, and it begins with “I saw the best minds of my generation.” Or is the iconic the simply the anthology poem, the signature piece, of each of that era’s major poets, the way “Red Wheel Barrow” was for William Carlos Williams or “I Know a Man” was for Robert Creeley? If so, then Hall’s generation has a couple of dozen, albeit almost exclusively focused around the New American Poetry. What about an “almost perfect” poem by somebody who is or was a decent, but hardly major poet, whether Gregory Corso’s “Marriage,” Denise Levertov’s “Scenes from the Life of the Peppertrees” or Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel”? Can a sequence or book be taken as an iconic poem, such as Williams’ Spring & All or Ted Berrigan’s Sonnets? Or a long poem itself, such as The Cantos or even just The Pisan Cantos, or “A” or Maximus?

Lets say, just for hypotheticals here, that the answer to most of these questions is affirmative. The iconic instance of language poetry would almost have to be Lyn Hejinian’s My Life. Yet it has been marketed as a novel, doesn’t have a single stable version, and Hejinian herself was a war baby rather than a boomer. Robert Grenier’s Sentences would seem to me to be as clearly a second such instance, albeit with the same kind of contingencies.

But here I think the contingencies of small press distribution – and the changing model of poet to audience during the past quarter century – comes into play. There are works, even books, that I would myself gladly characterize as iconic, defining not only of the poets themselves but of the period in which it was written, such as Bob Perelman’s 7 Works or David Bromige’s My Poetry. But those books have been out of print for decades now, even if it is impossible for me to conceive of any list of “top twenty” books of the past three or four decades without them.

There is also the issue of works that are personally important to one, but which may not be the poems that most people immediately think of when they hear a given poet’s name. For example, I would expect most people to think of Progress when they hear the name Barrett Watten, but I always also think of “Factors Influencing the Weather,” and all three of the texts collected in Plasma / Paralleles / “X” – poems that had a tremendous impact on my sense of what is possible in this genre. I can’t conceive of contemporary poetry without them, tho you may not feel this way about them yourself.

Which I think shows me where the problem lies – there really is no good definition of iconic. Who is to say that the memorable popular verse of a famously bad poet (Edgar Guest, Ogden Nash, Billy Collins) couldn’t be defined as iconic? What then would be the value in the term?

So I come back to my original definition. The only truly iconic poem I can think of over the past two generations, maybe three, is Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Am I wrong?