I finally got around to seeing Ron Howard’s film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code and it’s every bit the disaster that the reviews said the film was when it first came out. If you have never read the book, this flick, just released to DVD in time for your heretical holidays, very probably is going to seem unintelligible, moving as rapidly as it does, virtually leaping from plot point to plot point without the slightest pause for reflection. The characters have no opportunity to gain any real sense of connection with one another. Why the Parisian police cryptologist is rescuing the American “symbologist” (sic) is never very clear, nor why he believes her when she insists he’s in danger in the first place.

The essence of this story is that three sets of people, each with very different motives, are racing to solve the very same mystery, a puzzle in the form of a treasure hunt, the object the secret, literally, of the Holy Grail. Even in the book, the narrative is complicated to the edge of intelligibility because one of the three operates parasitically, letting the others do all the work, intervening just enough to make everyone’s actions a little muddy. Here, to squeeze everything into two-plus hours, Howard has drained the monks of any inner life they might have had, so that we are given just enough detail about their actions to understand that Our Heroes are at risk. But everyone feels instead as if they have been trimmed back to stick figures. The result seems more like you’re looking at the story boards for a motion picture than a film itself.

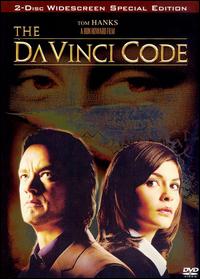

It’s a waste of good actors, doubly so since so many of them – Tom Hanks, Audrey Tautou, Jean Reno, Alfred Molina – are terribly miscast for their roles. You want them to have the time somewhere to try & develop (rescue) their characters, even just as an acting exercise, and it makes you wish that Howard had either stripped out perhaps an hour’s worth of plot, or else given himself the extra time – this film is long & feels much longer – to do this. There are moments in the film – the bank manager’s betrayal, for example – that seem to exist entirely out of all context, because his back story is completely missing & he acts thus without motivation.

In the end, this film really fails either because Ron Howard lacks self confidence – he has shown in the past that he knows better, even if he is a relentlessly Hollywood director, not the sort of brooding type who might have had more intuitive sense about the film’s spirit of darkness (it’s more than how you light the scene, Opie) – or because Ron Howard doesn’t have the power to make this his own film in the face of bottom-line driven execs.

So the problem is that it’s the author’s film that’s been made. As I’ve noted before in some detail, Dan Brown is a hack & the book itself is little more than a hyperactive plot machine. But it was a monster success and is no doubt what audiences expect. Yet consider, instead, how Peter Jackson & his writing partners far more successfully adapted The Lord of the Rings, omitting major characters, developing one entire picture out of a couple of paragraphs. Howard & screenwriter Akiva Goldsman (Cinderella Man; I, Robot; A Beautiful Mind) collaborate instead to give us a faithful but surprisingly unguided tour of the original plot, adding in only the smallest new details to try & keep some of the book’s narrative gaps – most notably the motivations of French police captain Bezu Fache (Jean Reno) – from sinking this bloated mess even deeper.

Because it’s Brown’s film more than Howard’s, taking some extra time to develop the characters & their evolving relationship to one another is pointless – they’re hardly any deeper in the book, although there readers get to see quite a bit more from the perspectives of Sophie, Silas, the Bishop, the banker, even the butler than we do in the film. And, contra Tolkien (or for that matter, Harry Potter, the other big film adaptation franchise of late), the myriad plot points are what the book is about. If it feels like a roller coaster ride, that’s because it is a roller coaster ride.

So often when films fail, it is because of bad writing. The producers spend a fortune on stars, sets, special effects, but appear to have forgotten to hire a writer. The variable history of Philip K. Dick stories as motion pictures could itself become a film course in the strategies of adaptation. The tales that work best as film – Blade Runner, Minority Report – are sometimes the flimsiest of Dick’s works, because in the movies, it’s easier to build from too little than it is to cut from too much. And, in sharp contrast to Brown’s bad book, few viewers of a Dick film are sitting in the theater with checklists ascertaining the veracity of the translation from page to screen.

This film fails as writing also, but not at the tactical level of bad dialog. It fails instead on writing’s broadest horizon: envisioning just what the experience of the film should be.