Written between 1919 & 1921, & published in 1927 in a Russian émigré journal, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s short novel We insured that he would never again be permitted to publish inside of Joe Stalin’s Soviet state. The one-time naval engineer, who at one point had supervised the construction of Soviet icebreakers in British shipyards, and who may have chosen the names of his characters – D-503, I-330, S-4711 – from the specifications for the ship Saint Alexander Nevsky, creates a simple-enough fable of a dystopian future that would serve as a model for both Brave New World and 1984. Persuaded by the presence of a Bruce Sterling introduction, I picked up the Natasha Randall translation because I was looking for something short to read during a month when I had two long business trips before starting what I expect will be the novel that will take up my fiction reading for the rest of this year, Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day. Even though We has a significant pedigree – “the best single work of science fiction yet written” says Ursula K. Le Guin on the book’s front cover – I was surprised by just how much I liked this book.

Partly this is because of the ways in which Zamyatin, born the same year as H.D. & just a year younger than Pound, foretells elements of the future, such as the creation of the Berlin Wall, decades in advance. Partly it’s because this is a passionate tale that falls outside of genre boundaries, even tho it is now routinely treated – viz. Le Guin – as part of the history of sci-fi. The story line really is the Garden of Eden inverted. After centuries of war, the civilization known here as The One State is, in fact, a city walled off from the external world, run by a dictatorial Benefactor as a technocratic and rationalist utopia. Families & religion are abolished, people literally live in glass apartment buildings and must request permission to lower their blinds for pre-assigned sexual liaisons, which are scheduled in advance by ticket (one senses that nobody would ever think to say No). D-503 is the master builder of the Integral, the city state’s projected entry into space travel and as committed a bureaucrat as you could imagine. All of this goes to hell (more or less literally) when D-503 finds himself falling in love with one of his sexual partners, I-330, who is something of a terrorist, determined to Tear Down This Wall.

The sexual frankness & sometimes daft combinations of retro-industrialism & futurama reads like a scramble of genres and some of the details – such as indicating just how far into the future this is by periodically noting the presence of gills on all the main characters even if the most advanced communications technology appears to be radio or the vague descriptions of “aeros,” the individual flying systems some (tho not all) of the characters appear to have access to – actually gives the book some of the rough feel one gets, say, from a Philip K. Dick book, where the futuristic elaboration of detail (think Asimov or Arthur C. Clarke) just isn’t a value.

It’s worth noting the degree, tho, to which, even as early as 1921 – when Lenin is still alive & nine years before Mayakovsky will commit suicide – Zamyatin grasps the problems of the totalitarian state. Inhabitants of the

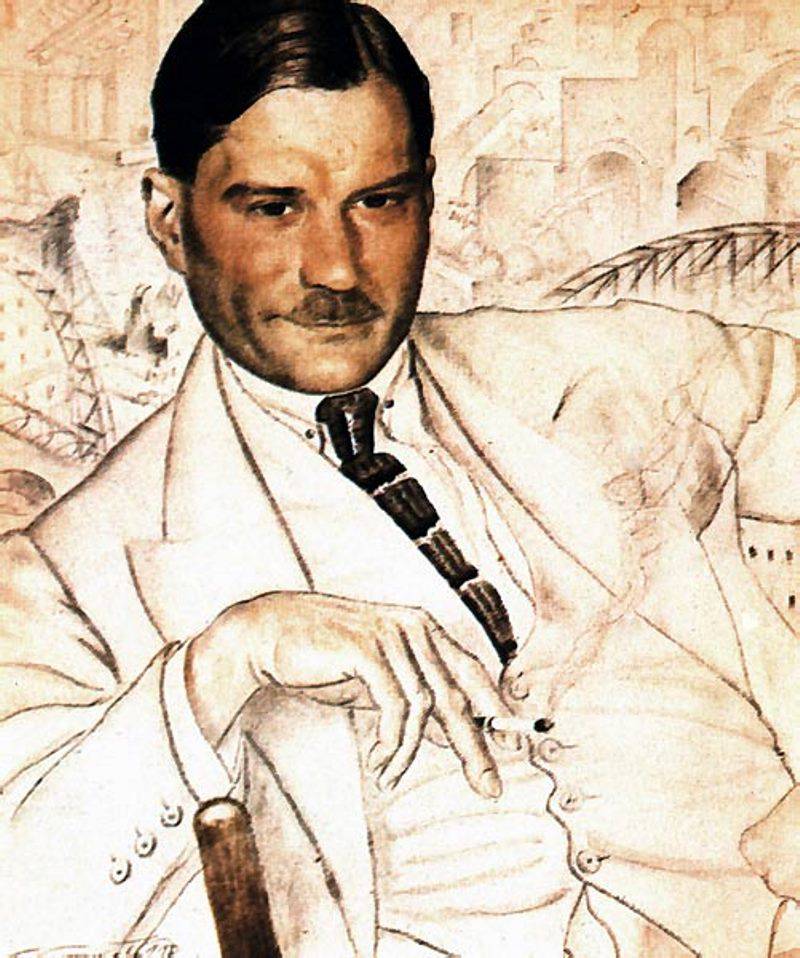

Zamyatin didn’t fare a whole lot better than his character. Perpetually in trouble with the authorities (both before & after the Bolsheviks took control), he finally emigrated to France where he co-wrote the screenplay for Jean Renoir’s version of The Lower Depths, but mostly scraped by in poverty before dying of a heart attack at the age of 53. Wikipedia notes that he’s buried on Rue du Stalingrad in Thiais, south of

Randall’s translation is quite good, tho occasionally she picks a contemporary idiom that sounds out of place for a book written in 1921, albeit set centuries, if not millennia, in the future. Part of what makes this works, I think, is Randall’s own training not as a poet but as a physicist, not that removed from the concerns either of the engineer Zamyatin or those of his protagonist, the rocket scientist. This is, in its own way, a very left-brain cry for the joys of the irrational, the spontaneous, the truly committed. If you have any interest in the history of science fiction, this is a precursor you are certain one day to read & Randall’s edition is well suited to its task.