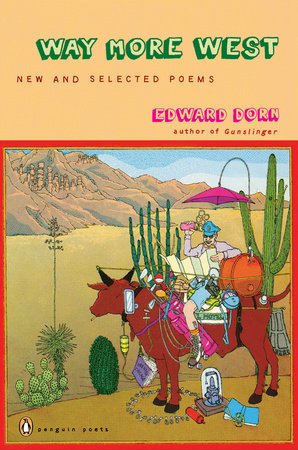

For a reader of my generation, a collection like Way More West: New and Selected Poems by the late Ed Dorn comes as a potentially useful corrective, not the least because it’s instructive to see that the relatively brief excerpt from ‘Slinger comes early, with more than half the book’s weight falling after the completion of this comic epic. Easily the most contentious and controversial of any of the New Americans – Amiri Baraka would be a pretty distant second on that scale – one version of the received wisdom about Dorn was that he was one of those rare individuals blessed with a natural lyric gift – the brilliance of a poem like “Vaquero,” one of Dorn’s earliest, and best known, poems would attest to that – who chafed at the intellectual demands of the projectivist poetics with which he was so closely aligned. In this reading, Dorn wrote What I See in The Maximus Poems as an attempt to come to terms with this challenge, and then produced one, perhaps two great books (depending on the version you heard – The North Atlantic Turbine was always cited, but some folks would argue for Geography as its equal), before flaming out spectacularly by writing Gunslinger, the metaphysical comic western that is, in many ways, a refutation of the projectivist program – a break not unlike the ones that Amiri Baraka & Denise Levertov would make as well. In all three cases, the received wisdom went, none of the apostates was to fulfill their early promise as poets. The villain in Baraka’s case supposedly was Maoism, in Levertov’s a fundamentalist feminism & in Dorn’s cocaine. In this telling, Dorn went off to noodle on some brief poems that basically showed him trying to relearn how to write, producing nothing of consequence unless you consider the bile that spilled forth during the Naropa Poetry Wars where the position of Dorn & Tom Clark opposing the excesses of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, which were considerable, was often taken, with evidence in print (and Dorn himself the publisher), to be racist, xenophobic & homophobic. But by then many, perhaps most, of the poets of my generation had long since stopped reading Dorn. Tho he lived the last several decades of his life in

There is no question that Dorn had difficult relations with his peers. When, in 1973 – pre-Naropa but post-‘Slinger – I got him to agree to read with Robert Creeley & Joanne Kyger in a benefit for the prison movement in California, Dorn’s one condition was that he be allowed to go last, so that he could arrive late & not have to speak to either Creeley or Kyger, with whom he was not then talking. It was the only time in my life I ever saw Creeley read first at such an event, but if Dorn took any pleasure in that, I couldn’t tell since Dorn didn’t arrive until right before he was to go on. His reading that night was terrific, that part is unquestionable, the first time I’d ever heard Recollections of Gran Apachería. But his behavior prepared me for all the claims later that he’d become the Mel Gibson of the New American Poetry. His remark years later that he didn’t need to read language poetry because

So it’s fascinating to see that the editor of Dorn’s new selected – it’s not the first & there was even a collected that went through three editions in the 1970s & ‘80s – is Michael Rothenberg, editor of Big Bridge & most recently the editor of Phil Whalen’s selected, also out from Penguin. Think about that. The editor of the poems of the writer most closely associated with Zen Buddhism in

It’s not that Way More West slights the early work – six of the nine sections of North Atlantic Turbine are present, plus more than half of Geography. If I have any qualms about the selection, it’s only the absence of any of the second volume of ‘Slinger, since that was the section in which it became clear that Dorn was not interested in going back to a world in which Charles Olson was the poetry equivalent of god-on-earth & Dorn the favored one among his potential successors. Since Gunslinger continues to be available – tho Duke rather stupidly hasn’t gotten that much of its backlist up on the website – this isn’t a major failing.

The real question is whether this Ed Dorn is as good or significant a poet as the

a bullet

is worth

a thousand bulletins

The first poem (in its entirety) from Abhorrences is a position that captures the Bush foreign policy in

Equating a seven-word poem to the

When Petra Kelly shot herself

I was right beside her in my heart

and my admiration for her steadfastness

was complete and totally unlike

what I feel for the black-boy whips of McDonna

or the earlier pretenders like Jane and Joan

in the brief history of corrective sensibility.

The careful mediation of her

American accent, the pure

german weltwaves in the background.

Certainment, why hang around

for the land to fill up with genetically resentful and

overproduced Southerners just so the pretenders

can get their carpets vacd?

The history of the world has been written

with the disappearing ink of those accounts

and the pilfered wages of their solution –

the sine qua non of population dumping.

¡Salute! and so long

For the price of a single round, you ducked

the destiny you described, and gave the colour to,

and framed – the born prophet

of a finale full of Fall Out, - Bye Bye.

Dorn of course gets it wrong. Petra Kelly didn’t shoot herself – she was shot and killed by her partner & whether it was a murder-suicide or a joint suicide is one of those unknowables of history – tho frankly the idea that it would have been the latter without the presence of any suicide note is extraordinarily improbable given Kelly’s life as a political activist. Misreading a sad act of depression & domestic violence as a political statement is sort of the archetypal stance of Ed Dorn. But what is he actually trying to say? That by dying Kelly is less of a “pretender” than Jane Fonda or Joan Baez? Given their starkly different political trajectories, it’s hard to know what point Dorn is making by conjoining them thus – that anyone who demonstrates is a pretender? Or perhaps just anyone with money, which I take to be the content behind the “

So what we get, finally, is a rather sad case – of all the New Americans, Dorn’s later poems rank up there with Diane DiPrima’s Revolutionary Letters as the silliest when it comes to their actual political thinking. And like Pound’s politics, it undercuts the poetry, even more so because Dorn has sacrificed so much of his poetics for this muddle of pissed-off agitprop. Consider Dorn’s poem “about” the case of Ezra Pound, entitled “Dismissal,” part of the last suite of poems, save for the cancer odes of Chemo Sábe, Dorn was to write. Its first stanza notes that Pound “made anti-Semitism a heresy, / although he wasn’t the greatest anti-Semite of his time. / Or even close.” Which is true enough, tho it’s worth noting as Ben Friedlander has, that Pound was considerably more anti-Semitic than, say, Mussolini. What gets me most, tho, is the next stanza:

A Modern gang of cutthroats

in cartoon berets, with sumo champions

like Gertrude Stein –

The giant abbreviator from

who wrote, stuttering

pseudo-wise hymns to war, and

its effects on the adventurous sector

of the lower / upper middle class.

There is an implicit, well not so implicit as cheaply explicit, homophobia in making fun of Gertrude Stein’s weight, but the connection to Hemingway, made with no more than a dash & linebreak & no verb phrase for either side of this equation. What is being said here? Are Stein & Hemingway the anti-Pound gang of cutthroats? Or merely a front for same, these otherwise unnamed figures “in cartoon berets.” Dorn takes up three stanzas & a section title to simply note that there was no trial. “Besides / insanity is the ultimate dismissal!” Then come two further stanzas that carry the implications further:

It was too familiar, a fitting end

to the old, uniformed fascism of the two wars

gliding into the transpace of the new

hierarchical oriental fascism of beehive

conformity, industry devoted only to survival

and ruinous increase. Singularity,

the swamping of the gene swamp.

All of it fondly called

the Modern Movement by those

who fervently hope it is over

and that their banal attempt

to get rid of a whole period

by driving a stake through it

will finally give them an end

to their belaboring the scapegoat.

One might reasonably read this as arguing that state fascism is being replaced by its corporate counterpart, and that modernism is about to be canned by the School of Quietude (parts of which did, in fact, attempt to ban Pound’s works, led by sonneteer & 1934 Pulitzer winner Robert Silliman Hillyer), using Pound to drive “a stake through it.” Why, however, the gratuitous racism of oriental midway through the first stanza above – there’s been no discussion anywhere here of Japanese or Asian capitalism, let alone the outsourcing of manufacturing to

There is more than a little Pound in Dorn. Imagine ‘Slinger as Dorn’s Mauberly, but that the only “Cantos” that follow turn out to be those devoted to Martin Van Buren & that he dies before he can be rehabilitated poetically in Pisa. You would get a selected that feels not so terribly different from Way More West. It’s a career arc that is functionally going over the cliff even with Gran Apachería, and it makes you reread all the earlier work, and especially the ellipses in the earlier work, not as moments of Olsonian leaps, but as real gaps in thinking.

There is a story worth telling – it would make a great doctoral dissertation, frankly – about what happened in the 1960s to the New American poets: who got political, like Ginsberg, Baraka, Levertov & Margaret Randall, who merely played at being political like Diane DiPrima, who incorporated the political into their work (Duncan, Zukofsky, Oppen), who freaked at the idea of poets as political such as Jack Spicer, who stayed silent throughout (Ashbery, for one, but pretty much every NY School poet not named David Shapiro), who actively rooted for the far right (Kerouac), etc. If the aesthetic reign of the New Americans proved short lived (even as their impact continues to resound and expand to this day) a lot of this has to do with their movement being a quintessentially post-World War 2 phenomenon. It was never prepared to survive drugs, the Beatles or