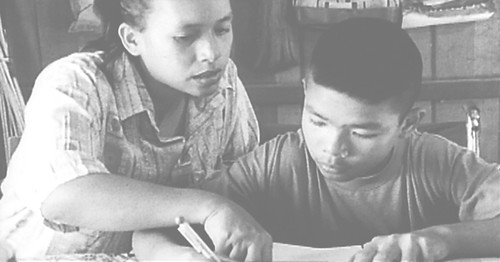

The strangest film I’ve seen in some time is an experimental docu-drama from Thailand called Mysterious Object at Noon, directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a Thai architect who has an MFA in film from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (which, when you think about it, is a great town for an architect to go to in order to study film). It’s not a docu-drama in the American sense of the word, but rather a film that documents a narrative, the tale of a home study teacher and her disabled student. How it does this is what is so unusual. Working for over three years with an all-volunteer cast & crew – which also means an ever-changing cast & crew – Weerasethakul employed the surrealist game of the Exquisite Corpse, which, as described by one web site devoted to this practice,

was played by several people, each of whom would write a phrase on a sheet of paper, fold the paper to conceal part of it, and pass it on to the next player for his contribution

Now imagine playing this same game with film, not only with the urban elites of Bangkok, but with villagers in Weerasethakul’s native north who have only limited experience with cinema and no real concept of fiction. The results are both primitive and startling. Filmed in black & white with the cheapest imaginable equipment and film stock, Mysterious Object is something akin to a surrealist version of Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera set in the Thailand of the 1990s, which means everything from contemporary skyscrapers and freeway onramps to elephants wandering into the scene as some boys who’ve been playing a version of hacky sack try to improvise what might come next. One group of villagers act out their section, which includes music (some of it involving a mouth organ unlike anything I’ve ever seen before). Another woman, early on, simply tells her own story, which involves being sold by her father in return for bus fare. There is a long truck ride through

This film works for many of the same reasons that any artwork that is actively trying to invent its own genre does – in this sense, Man with a Movie Camera, as well as books as diverse as Tristram Shandy, The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, Moby Dick, Spring & All and Visions of Cody, are almost parallel projects. Each questions everything and makes no assumptions as to how to proceed. In this context, even a wrong decision (presuming of course we could define such) would be a fresh one. At the same time, Weerasethakul clearly understands this role as historical – there is a scene in which the film-maker and his colleagues are walking along & one comments “We should have had a script.” The film ends when & where it does because that’s where, literally, the film stock Weerasethakul had at his disposal ran out.

If you don’t care for experimental cinema, you can almost be certain that you’re going to hate this film. Even if you love the work of Stan Brakhage, Warren Sonbert & Abigail Child, you may find it hard to imagine that something like this can still be produced in the 21st century. Would it still hold its fascination if the film were in English about