I generally despise I-95 & there’s nothing about the Memorial Day Weekend that is apt to make me love it any more deeply. As it happened, I had to view the aftermath of what appeared to be a fatal accident near

As an audio-book, Doctor Sax is a hoot & a half, as a number of readers work their through a screenplay Kerouac wrote based on his novel, accompanied by an occasional sound-effect (balls scattering on a pool table, etc.) and a reasonably decent score by John Medeski. Of the 14 voices heard on this 2-CD affair, two have considerably more than half of all the air time – the narrator, spoken by the late Robert Creeley, the one role in this project that demands (and gets) a fair amount of quiet subtlety, & a variety of characters all given voice by poet-rock star Jim Carroll, who generally does a good job distinguishing between his roles & pulls off an utterly spooky Peter Lorre imitation in the process. Doctor Sax is spoken by Grateful Dead lyricist & poet Robert Hunter, who frankly sounds too healthy for a character that seems to have been based in part on Kerouac’s roommate during the penning of Sax, William S. Burroughs. The wizard Faustus is portrayed by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who plays the role as tho he were the old character actor Gabby Hayes. All the players appear to be having a blast & the pleasure is contagious. I was able to listen to the entire project straight through twice with only one day between sessions & never once suffered a moment’s boredom.

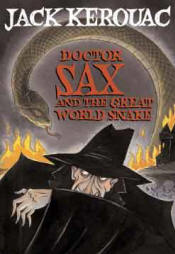

Sax is a novel that was published, like so much of Kerouac’s writing, to mixed reviews. This is especially true for those books that focus not on Kerouac’s life as an wandering anti-authoritarian minstrel & wastrel but his childhood. But in some sense, Sax is to Kerouac’s understanding of himself what The Prelude was to Wordsworth. This is really the tale of the growth of a poet’s mind, but as a troubled kid (and one who doesn’t get it that he’s troubled). Functionally, the story operates as a series of concentric tales, each more extreme (and disturbed) than the one before. In the first, Jacky Duluoz is a kid who plays hooky in order to stay home and play fantasy games of horse racing using marbles & ball-bearings. In the second, Jacky is both detective & miscreant in a mystery to catch The Black Thief,. a neighborhood criminal who specializes in stealing the toys of Duluoz’ friends. The Black Thief’s undoing comes as a result of leaving his taunting notes behind on the same orange paper that young Duluoz uses to practice his writing skills, literally trying to verbally sketch out commonplace physical elements of the neighborhood (50-plus years later, this is recognizable as a classic writing exercise, but it’s fascinating to see Kerouac suggest that he was compulsively working at his skills at depiction at what must have been no more than the age of ten). The third tale is Duluoz’ interactions with the realms of the unknown, represented by Faustus, Count Condu, Doctor Sax, various vamps & wizard wives, and of course the Great World Snake that comes to threaten the world until it is carried off by a giant bird

SURROUNDED BY MY DOVES! MY DOVES, MY YOUNG AND SILLY DOVES!...... BIRDS OF PARADISE COMING TO SAVE MANKIND!

As Sax puts it. Kerouac’s mythology here is a mashup avant le lettre of Catholicism, Central European ghost stories & some over-the-top Freudian remnants that work precisely because they are such a motley combination. This is intermingled with some extraordinary instances of description, most of which comes through Creeley’s role, and a great ear for dialog. For example, what makes the above passage work is precisely the word “silly” in a context that seems so very jarring.

The production and direction of the entire project at the hands of Kerouac’s nephew Jim Sampas is rough, but serviceable. When Sampas first started taking active control of Kerouac’s archive I recall worrying that Sampas wasn’t going to get it and that he would want simply beatify his uncle whose very flaws – such as the deeply creepy sentimentalism toward Kerouac’s mother – really prove to be driving forces for Kerouac, even if what they drove him to was his much too young death from alcoholism. But in fact Sampas seems to be in touch with both the Kerouac who is appallingly crude & the one who is, for better or worse, the Jimi Hendrix of fictional prose. Under Sampas' direction, you can hear this troupe of friends making it up as they go along. In this early stages, for example, different characters pronounce Duluoz quite differently. For Creeley it is Də-looz, for Carrol it is Do-loo-ǎz, with the short a pronounced as in cats. But over the course of the recording most everyone comes to settle on Də-loo-ahz with the stress on the second syllable. This is the sort of detail that a professional would have gotten down before committing a moment to tape, but professionalism was not Kerouac’s claim to writing – quite the opposite – and its absence here makes for texture, not problems.