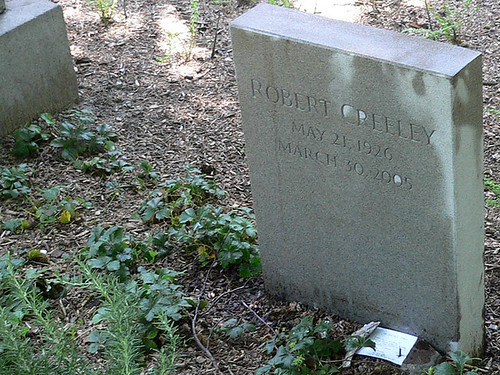

photo by Tom Raworth

We are no doubt going to see a fair number of books quite like Mark Jay Mirsky’s memoir, Creeley, published as a chapbook by Pressed Wafer of Boston. When someone who is important to a lot of people dies, the survivors stand around and tell stories – in eulogies, over drinks at wakes & later in memoirs. The stories are loving & a few of them might even be scandalous, as their point isn’t to discuss the poet’s oeuvre or career, but rather the person. And hardly anything humanizes an individual more than their flaws. Many of the New American Poets have been the subject of terrific memoirs, most notably Charles Olson, Frank O’Hara & Ted Berrigan. Creeley, who functioned more or less as the dean of American poetry for close to 40 years, is certain to have his.

The novelist Mark Jay Mirsky isn’t necessarily the person you would expect to be the first one out of the chute with such a venture, perhaps because his aesthetics don’t seem especially Creeley-esque, or because he seems such a quintessential New York guy, or just because he’s 13 years younger than his subject, young enough so that Bob was always going to be the Elder in that relationship. Elder brother, as it happens – Mirsky seems to have turned to Creeley as much for life lessons as for those concerning writing, and – like so many other younger writers – discovered a remarkably open & generous person, willing pretty much to share anything.

So we see Creeley very much in the mode that will be familiar to so many younger writers – and at 60, I’d include myself and anyone in my own age group there as well. Creeley was born the same year as my own mother, one ahead of my father, which means that he went through his life tasks pretty much at the same time as did they, although my own dad got through his three marriages much faster than Bob.

But we also get to see Creeley the drunk & Creeley the brawler, even more so than in Ekbert Faas’ abortive bio. This is a side of Creeley that I never saw personally, tho it was impossible not to hear about it in the 1960s. I recall one discussion among young poets in the 1970s as people tried to guess just how much Creeley spent on alcohol each month – the final consensus was something like $300. Mirsky’s take on this actually is much less lurid than the tales one heard – he describes Creeley’s friends in Bolinas getting out of his way at the bar as he tried to take on anyone who would fight, Creeley literally falling against the pool table, blackening his one good eye & only the next day discovering that nobody had clocked him one in legitimate combat.

For such a short book – just 24 pages – Mirsky is quite a rambler. Some episodes are here not because they’re about Creeley so much as the fact that they’re simply good stories. The best example of this is a tale involving the British novelist Ann Quin:

Bob was reading with Ted Hughes and, I think, Auden, at that grand theatre by the

Some years later, Ann walked into the sea.

Creeley may be the occasion for this tale, but it’s hardly about him. We never learn what he read, nor how he comported himself alongside such hobnobs of British conservatism as Auden or Hughes, nor functionally anything else about this reading. Indeed, not only is this not a book about Creeley the writer, but I’ve virtually never come across a memoir that shed less ink on that side of a poet’s life.

One area where Mirsky does cast new light concerns something I’d never thought of in quite this way before – the breach between the New Americans and the Boston Brahmins that was so central to the division between post-avant &

the quintessential Harvard man of a certain period, hair meticulously combed, suit and tie with the touch of modesty that bespeaks the glass of fashion

– being genuinely vicious about the country bumpkin Creeley. Creeley’s father had been a doctor, but had died when Bob was quite young, leaving the family pretty much in poverty with only the mother’s inadequate salary as a nurse to sustain them. Olson’s father had been a mailman. Indeed, hardly anyone among the

So Mirsky’s Creeley isn’t the whole of the man & doesn’t even approach the writing, as such. But it’s a useful – and voyeuristically enjoyable – road in to thinking about one of the two or three most influential poets of the past half century, and the elements that went into making him the particular poet he became.