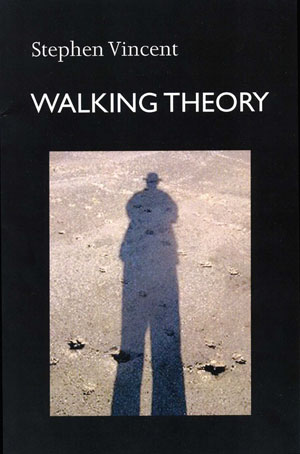

Saturday afternoon, I came back from a long walk in Jenkins Arboretum – it’s azalea season here in Chester County & the arboretum is one of the great azalea & shade gardens – brought in & opened the mail, then lay on the couch with the three new books that had come that day & promptly fell asleep. When I woke, refreshed by that rare (for me) phenomenon of a mid-day nap, I thought to glance through the books & opened Stephen Vincent’s Walking Theory from Mark Weiss’ Junction Press. I started reading & just couldn’t stop. It’s not like Walking Theory is a chapbook – it’s 84 pages long – and for me reading anything longer than a one-page broadside-brochure in a single sitting is quite unusual. But Walking Theory is not a usual book. These are the poems Stephen Vincent has been preparing to write his entire life. They definitely pass the “take the top of your head off” test. I went cover to cover without even sitting up.

The walk as a unit of writing is not new to Vincent – his last book was called Walking & the relationship between the two volumes reminds me a little of how, when you saw David Antin’s first couple of books of talks, you sensed yourself in the presence of a supple & evolving form that one could expand & explore potentially for the rest of one’s life. It’s an experience-based unit of writing, not unlike “the sitting” – still the most common & least acknowledged verse unit there is – and one with some history & orientation. One could trace it, especially through, say, Phil Whalen or the circumambulations of Gary Snyder, back to the travel writing of

Walking Theory is a book of elegies, so that the walk itself is not just a mode of urban (and in some instances coastal) exploration & a good form of exercise for someone getting comfortable with the second half-century of his existence, it’s literally about walking off grief, directly, indirectly, every which way. Grief is as essential to this process of walking as breathing is to meditation. But one could say just as easily that walking is as essential to grief, etc. You can’t separate them out, the chicken from the egg of emotion. This book is pure emotion:

Grieve in the morning.

Grieve in the afternoon.

Grieve. Grieve.

Your mother. Your father.

You friend. Your lover. The brother,

sister, son and daughter.

Unto the fourth day, unto the fifth,

upon the waters. Upon the night. Upon the day.

Grieve.

Or, also from “Elegy in Red”:

Go away little

death Angel.

Get off my back door.

Isn’t your father lonely?

Your mother home alone?

Go away, go away

little death Angel.

Break bread with the ancestors,

with the long dead.

Break bread with the moss on the oak,

Heaven leaves her morsels

on a stone.

Or, still deeper into this same poem:

How to put the death raft out.

How to put my brother’s body on the raft.

How to sing the song, a farewell song.

How to garland the raft with flowers.

How to pick the man or woman to guide the tiller.

How to watch the raft float by.

How to know the stream flows dark and deep.

How to know he will not come back.

How to know when to sing.

When to witness the trail,

the tracks and wheels,

the grooves in the earth

that brought him to

this river’s bank.

How to know when to weep.

It’s a misrepresentation, really, of Walking Theory, for me to quote only these works with so much parallelism. There is a ton of play here, and a shining wit – this actually isn’t a “heavy” or gloomy book in the slightest, once you acknowledge that grief also is a part of life. Vincent has a good sense of the line – I think that’s self-evident above – and a good ear for the spoken word as well. Some of the very best passages are pure quotation, such as these two from the long title poem:

35

”How are your dreams, Mom?”

”Oh, the other day, I wish

I had written it down. It was fantastic.

It was really something. I remembered it

All day long. It’s too bad

I didn’t write it down.”

36

”The sun is always sending out

bursts of energy.

I’ve been on one

Since early this week.”

Anonymous Voice, KPFA Radio, June 2004

Stephen Vincent has always been a personal poet & in his early work, such as his selection in Five on the Western Edge, the collection Vincent edited & published of Bay Area poets in the mid-seventies¹, I felt that to be a weakness, that it led toward sentimentality. But instead of stripping the personal out of his poems, Vincent has done just the opposite: he’s embraced it to a degree that I haven’t seen outside of the early books of Allen Ginsberg. Doing so, the sentiment, that buffer between what we feel & what we think we should feel, is what’s been stripped away. The result is a luminous record of a life, a family & a community. Walking Theory is a terrific book.

¹ In many ways Five is as good a record of