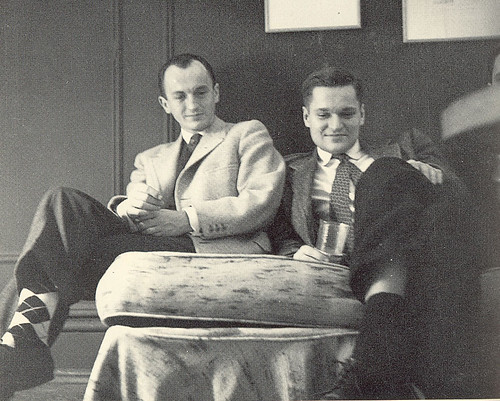

Frank O’Hara (left) & John Ashbery, 1953 (photo by Kenneth Koch)

Back when Robert Duncan & Jerome Rothenberg were just about the only poets actively advocating for the work of Gertrude Stein – Richard Kostelanetz, somewhat younger, came later, bringing with him the energy to get a lot of her work back into print – the one poet who seems to have actually grasped the implications of her literary interventions & to have brought them over into his own poetry is John Ashbery. What I’m thinking of, specifically, is the coloration of words & the impact this has on the affect of any given textual surface.

One sees it, of course, early on in Stein – it’s almost the point of Tender Buttons. As she writes at the start of “Breakfast,”

A change, a final change includes potatoes. This is no authority for the abuse of cheese. What language can instruct any fellow.

A shining breakfast, a breakfast shining, no dispute, no practice, nothing, nothing at all.

A sudden slide changes the whole plate, it does so suddenly.

An imitation, more imitation, imitation succeed imitations.

Stein’s work recognizes what Robert Creeley would only much later be able to articulate theoretically as

A poem denies its end in any descriptive act, I mean any act which leaves the attention outside the poem. (1953)

In other words, poems are not referential, or at least not importantly so. (1963)

Yet if nouns don’t name objects that exist outside the poem, what is it they do? As Tender Buttons suggests & Ashbery will spend a lifetime demonstrating, they color the text. After all, as Stein says in “Poetry and Grammar,”

Poetry has to do with vocabulary just as prose has not.

Today, there are many clear instances of this – the way Clark Coolidge drains referential terms from The Maintains (This Press, 1974) only to bring them back again in that book’s companion work, Polaroid (Big Sky, 1975), or how Larry Eigner would use the most generic of nouns – tree, sky, cloud, bird – almost architecturally in his poems. But certainly the poem where I first noticed this is in Ashbery’s “Into the Dusk-Charged Air,” one of the great poems in Rivers and Mountains. Although it is not the title work of that book – a brilliant gesture, given its focus precisely on the names of rivers throughout the world – nor the “long poem” masterwork (“The Skaters”) that in some ways makes this volume a rehearsal for Ashbery’s Double Dream books, the function of names in “Dusk-Charged Air” is unmistakable:

Far from the

The brown and green

Like the Niagara’s welling descent.

Tractors stood on the green banks of the

Near where it joined the

The St. Lawrence prods among the black stones

And mud. But the

Wind ruffles the

Surface. The Irawaddy is overflowing.

But the yellowish, gray

is contained within steep banks. The Isar

Flows too fast to swim in in, the

Courses over the flat land. The Allegheny and its boats

Were dark blue. The Moskowa is

Gray boats. The Amstel flows slowly.

And so forth for another 3.5 pages. I’ve always thought of “Dusk-Charged Air” as being the next step for Ashbery after “

I thought that if I could put it all down, that would be one way. And next the thought came to me that to leave all out would be another, and truer, way.

clean-washed sea

The flowers were.

These are examples of leaving out. But, forget as we will, something some comes to stand in their place. Not the truth, perhaps, but – yourself. If is you who made this, therefore you are true. But the truth has passed on

to divide all.

Against the radical disruption of leaving all out, as in “Europe,” poems like “Into the Dusk-Charged Air” or, say, “Farm Instruments and Rutabagas in a Landscape,” the famous sestina that lies at the heart of Double Dream of Spring with its own landscape populated by the characters of Popeye, seem to offer the same lesson from a very different angle. The use of names in each was, at the time these poems were first written, so atypical as to burst out at one not unlike the image of a Brillo box or a Cambell soup can or Jasper Johns’ use of the American flag.

Thus if poetry is about vocabulary & poems themselves are not referential, we have – no one is more clear about this than Ashbery – a hierarchy of vocabulary. At the pinnacle are the three great orienting pronouns, I, you and we, followed very closely by proper names – Rappahannock or Wimpy or whatever – followed by nouns, as such, then adverbs & verbs and then all other words. It is worth noting that what puts the three pronouns at the pinnacle is their implication of presence, these invariably are the pronouns of immanence, as he, she and they are not.

Because he is so attuned to the implications of this hierarchy, one might in turn order all of Ashbery’s poems by how they utilize it. A poem like “Into the Dusk-Charged Air” focuses in at the level of the name, but Three Poems is a book almost entirely lacking in them. The absence of is so pronounced that when one does turn up – “dull Acheron” on page 21 for example – it comes as a jolt even when, as here, the point is precisely its non-jolting nature. This, in turn, elevates the role of the three pronouns, all of which appear on the first page, and in a sequences that seems not accidental or even casual – at least not here where Ashbery is setting up the project as a whole. The privileged pronoun, at least in “The New Spirit," and the earlier stages of this book, exactly as Ashbery suggests on, is you, a term that is decidedly slipperier than either I or we, because, as here, it can – but doesn’t have to – imply writer as well as reader:

You are my calm world.

*

You were always a living

But a secret person

*

Such particulars you mouthed, all leading back into the underlying question: was it you?

*

And yet you see yourself growing up around the other, posited life, afraid for its inertness and afraid for yourself, intimidated and defensive. And you lacerate yourself so as to say, These wounds are me. I cannot let you live your life this way, and at the same time I am slurped into it, falling on top of you and falling with you.

*

You know that emptiness that was the only way you could express a thing?

*

To you:

I could still put everything in and have it come out even, that is have it come out so you and I would be equal at the end of our lives, which would have been lived fully and without strain.

*

Is it correct for me to use you to demonstrate all this?

*

You private person.

*

And so a new you takes shape.

These are just a smattering of the you statements that appear over the first twenty pages of “The New Spirit,” so that when the speaker of the poem proclaims

we remain separate forever

we just don’t believe it, particularly when this self-same sentence continues after a comma,

and this confers an admittedly somewhat wistful beauty on the polarity that is our firm contact and uneven stage of development at this moment which threatens to be the last, unless the bottle with the genie squealing inside be again miraculously stumbled on, or a roc, its abrasive eye scouring the endless expanses of the plateau, appear at first like a black dot in the distance that little by little gets larger, beating its wings in purposeful and level flight.

Reading this text for who knows how many times over the 35 years I’ve owned this book, I find it hard not to laugh at the passage that follows, given the directness of its statement about the referentiality of the poem:

I urge you one last time to reconsider. You can feel the wind in the room, the curtains are moving in the draft and a door slowly closes. Think of what it must be outside.

If you can hear in that passage the allusion to Creeley, to Hamlet, even to Faulkner’s own use of the arras veil, all the better. For a text that literally, deliberately, goes nowhere – and does so again & again – “The New Spirit” and all of Three Poems is filled with such magical moments that are, as I read it, the point.

This is not a point that can be made through exposition as a hierarchic argument, a flow chart of consequences, syllogisms locking into place. It demands instead a process-centric approach to meaning. There is a reason that Ashbery’s poems, even the contained lyrics of the Double Dream books, resist, as I wrote the other day, “going anywhere.” Nowhere is this resistance more fully enacted than in Three Poems.