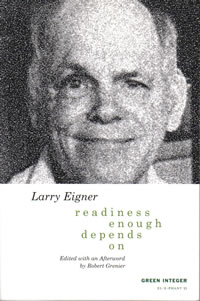

It took me a long time – seven years – to read Larry Eigner’s last works, readiness / enough / depends / on. Green Integer is the post-avant press least likely to send me a review copy of anything, and I never see its wares in bookstores unless I happen to be visiting Small Press Distribution in

It’s no accident that In the American Tree is dedicated to Larry. His impact on my generation was enormous. While he’d originally become known in the 1960s as one of the Projectivist Poets – he’s included in the “Black Mountain” section of the Allen anthology, tho he never visited the college to my knowledge & certainly couldn’t have been scoring his own speech for the printed page, given the impact that cerebral palsy had on his capacity to form words – Eigner really was a philosopher of consciousness who used poetry almost architecturally to sculpt the most marvelous observations of the particular, even when he chose the simplest categorical terms to plot this out. There is one poem in this relatively slender volume that is perhaps the apotheosis of this approach to the poem. Like most of Eigner’s works, it has no title other than the date of its composition, “

hills

earth

sky

night

clouds

Five nouns, no waiting. It proceeds from the particular to a more general category – hills are a synecdoche for earth, and one might say further that sky performs the same role for night. But not really. We have shifted from the physical to the temporal. That shift is in fact one of the meanings of the final term clouds. What is the relationship between the observable and these larger categories in our lives? If sky leads us to night (or alternately day), where does clouds take us? What ultimately do clouds mean? Is there a storm brewing or are these the lollipop puffballs of a serene evening? Eigner doesn’t answer that question.

It’s not unreasonable for a person unfamiliar with Eigner’s work to counter, when they hear a reading like the one above, that I’m getting an awful lot from five of the blandest words in the English language. To which really the only answer would appear to be that if you read all of Eigner, all two or three thousand poems that have appeared in books & journals, that he would type into his letters (or, worse, write with the faintest of pencils – his penmanship was worse than his speech, and for the same reasons), you’d realize that this text above can’t really be read any other way. Eigner’s economy of vocabulary and means may have once been prompted by the physical challenges of his palsy, but I think he must have understood almost at once the limitless power of brevity. He is, as a result, the most exacting of poets – if a word is two spaces to the right, there is a reason for it. Nothing is casual here, even for a poem that can be read in fewer than five seconds.

This also accounts for the sometimes strangely torqued grammar that, for example, can be found in this book’s title. I’ve always thought of this as what Eigner learned from Charles Olson in much the same way that his conciseness owes a debt to Robert Creeley. The key term in that sequence is in fact its last: on. Readiness enough depends on. What is that state of dependency, of contextuality, that lurks in this preposition? It’s as tho these maximally taut first three terms were driving through that last one – it’s no accident that the syllable count here moves steadily downward: three, two, two, one.

I was surprised to discover that Larry wrote just six poems in the nine months after I moved to

nice and how many times

Written on November 17, it’s one of the rare ones with a title, “Might Gertrude Stein Lie Open to Criticism?” to which the poem sounds like a joke response until you start to allow all the possible meanings of nice to filter in, that extra space between it and the four remaining words all the punctuation in the world. To this Eigner appended a note which editor Robert Grenier proves wise enough to leave in: I guess this is / what I had, though / now, dec. 9, it / seems to be. This is indeed what Larry Eigner had at the end of a long and fruitful life. As you permit all the possible connotations from that last phrase – it / seems to be – rise up & drift away, you realize just how very much that was.