The last time I saw Norman Mailer on the television – I never met him personally – he was on C-Span2 on one of that channel’s all-book days, talking at

One test of a great novelist, any great writer really, I’ve always thought lay in the size of their vocabulary and the ease with which they deployed it. I always come away from Shakespeare, for example, hyperconscious of how much more there is to the language than what I normally hear in daily life. Just this past week, after a phone presentation with one of the customers on my day job, a multibillion dollar global systems integrator, I got an email from the lead person on the customer’s team, thanking me for using the word “loquacious” & reminding him that a world existed where such terms could be used.

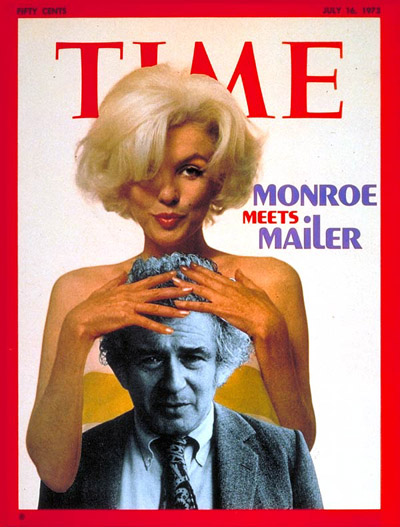

After the high modernists, especially Joyce & Faulkner, the two novelists who do the most to expand one’s vocabulary are Henry Miller & Norman Mailer. DeLillo & Pynchon aren’t bad in this regard, either. Miller of course is better known for the frankness of his writings on sex, but it’s the vocabulary’s scope that persuades me, not just the use of an occasional four-letter word.

With Mailer the two books that I find matter most are Armies of the Night, easily the best prose work about American political life in the 1960s, and the remarkably off-kilter Why Are We in Vietnam? I’ve always felt that latter book was an attempt to channel a later version of Jack Kerouac in a way that directly anticipates, of all people, Donna Haraway & Greg Tate. Here is just the first paragraph of “Intro Beep 1”:

Hip hole and hupmobile, Braunschweiger, you didn’t invite Geiger and his counter for nothing – hold tight young

It doesn’t quite work, which actually proves to be an important part of its charm, critical to the linguistic vertigo that sucks the reader in. 224 pages of this can feel exhausting, but you aren’t actually going to open up to the work until you get to that moment, not some sort of suspension of disbelief, but rather through disbelief completely. It’s a move that takes Mailer out of the pallid circuit of Bellow, Roth, Doctorow & Updike & places him more fairly against Kerouac, Olson, Melville. While I like Doctorow, only Mailer can write with the intensity, word to word, of those poet-novelists even if it doesn’t come through in everything he did.

Here be some links that popped up in the days since he died:

Boston Globe photo essay

Tributes from various folks,

including the President of France

From around Atlanta