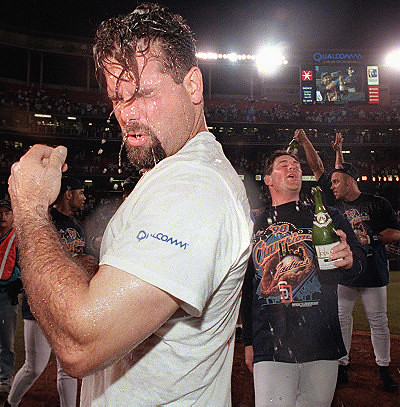

A muscled-up Ken Caminiti celebrates

winning the 1998 National League championship

with champagne. Caminiti, the 1996 NL MVP,

would be dead in six years.

Lyle Alzado was the first professional athlete I was aware of to cop to using steroids. Alzado was a football player who played for the Denver Broncos, Cleveland Browns & L.A. Raiders from 1971 into 1985. Alzado, who later became a professional wrestler & occasional actor, blamed steroids for the brain tumor that killed him at the age of 43 in 1992. What I remember about him – what made him stand out at the time at a position, defensive end, where frankly few football players ever garner fame – was the intensity with which he performed. Alzado on the field seemed driven by an insane rage. This made him very effective closing in on hapless quarterbacks, tho it also led to more than a few penalty flags over the course of his career. That’s a perennial problem with loose cannons: they go off in all directions.

Thursday’s report (PDF) to Major League Baseball (MLB) by George Mitchell reminded of this, in part because the years of Alzado’s career really predate baseball’s admission of its own “drug problem.” When Alzado died, the controversy of the role of steroids in his death caused these medications to get written up in all the sports sections. One of the side-effects, it seemed, was “’roid rage,” emotional volatility that was a direct reaction to many steroids. And quite effective at intimidating opponents on the field, at least if it was directed in the right direction.

Reading those articles at the time made me realize that I’d already seen one transparently obvious instance of ‘roid rage on the baseball diamond. It occurred in the 1990 American League championship series, which pitted the

This doesn’t mean that the Mitchell report is much of a document, however. With the exception of a couple of interviews that MLB effectively coerced, most of the documentation in the report amounts to old news clippings and hearsay. None of it would stand up in a court of law and most of the players named are not of the Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds type elites. Even without chemical enhancements, Clemens and Bonds were the best pitcher and best hitter of the era. If you don’t believe me, look at Bond’s strikeouts, which border on non-existent. That kind of coordination is not enhanced by muscle mass – if anything, just the opposite. Yet nobody has come close to Bonds in the last several decades in the old basic “see the ball, hit the ball” side of the game.

Which is why steroids don’t help every player – one of the 91 current or former players named in the report was David Bell, a hardnosed hustler of a third baseman who was a so-so fielder and an even worse hitter.

Ball players will do anything to survive and excel. Not long ago, an episode of Mythbusters demonstrated conclusively that corking a bat actually robs it of somewhere between ten and twenty percent of its power. Yet how many players have bought into the urban legend about the power of the corked bat and gotten caught – and suspended – for actually compromising their hitting power? They might as well have been hitting with microwaved poodles. The funny thing is that more than a few of these players have hit home runs with these compromised bats – the placebo effect is strong. As Yogi Berra says, “90 percent of baseball is half mental.” Whether Gaylord Perry threw the illegal spitball or not was a lot less important than the belief players had that he did. Perhaps he only threw it often enough to get caught and keep the myth alive.

What all of this means, I think, is this. Baseball has been abusing drugs much more widely, and for far longer, than the Mitchell report suggests. Olympic doping scandals date to the 1950s. The days when ballplayers could simply scoop up some “uppers,” “greenies” as Willie Mays used to call them, from a bowl in the locker room may be behind us, but it’s telling that the Mitchell report doesn’t address the ongoing problem of methamphetamines in the game. Just what would those day games after a night game look like if some folks weren’t buzzing around on speed?

I’m prepared to wager that there has not been a game since at least 1975 – if not 1945 – in which a minimum of two players on either side were not somehow “enhanced.” After all, Mitchell got 91 names basically from a Lexis-Nexis search plus a pair of interviews. What if he’d had subpoena power and access to the trainers for all thirty teams? We’re not talking dozens of violators, we’re talking hundreds, perhaps thousands. Just look at Wikipedia’s list of athletes penalized in doping scandals, only a tiny fraction of who played baseball. Which means that it has been the norm, not the exception. Athletes will do anything to improve the odds in their favor. If there is a culture of acceptance, they will push the envelope that much further. Is this any worse than software programmers living off of Jolt and working until three in the morning, or fighter pilots in Iraq using “go pills?”

It can be for the players. Steroids are nasty meds. Most any asthmatic in the

Performance enhancing medications simply underwrite the much broader drug culture in sports, which includes hard drugs and bad habits like needle sharing. I’m not concerned that a ball player may get high. But I am concerned about a Ken Caminiti dying of an overdose or an Alan Wiggins dying of AIDS. That’s the real price of drugs in sports. Just like rock ‘n’ roll.

What is most depressing here is the charade of mock righteousness on the part of owners and baseball executives – including the Giants’ Brian Sabean who was warned about Bonds’ activities and never spoke up, and Bud Selig, one-time owner of the Milwaukee Brewers during this very same period (ever check out the muscles of Rob Deer, Bud?) … and even that former owner of Texas Rangers & one-time employer of Sammy Sosa, George W. Bush. It’s the owners far more than the individual players who are culpable in this sad affair. If there is a culture of permission, it begins there. Relatively little of this could occur without the tacit acceptance of baseball execs, anxious to see their product performed at the “highest” level. If there are a few casualties along the way – Hey, I’m not the one shooting myself up in the butt every day. And pass me that cosmo. If Selig wants to hand out suspensions or expulsions, these are the folks who should go first. Don’t hold your breath.

The other group that I find completely appalling in all this are the sportswriters, a profession itself that has always lived large off of chemical enhancements, in its case mostly alcohol. The thought of one more self-righteous diatribe from a red-eyed sports hack about the “purity” of this pastime – the very same game that Cap Anson organized in the 1870s to expel players of color & which threw its world championship in 1919, and which brags to this day about the feats of Babe Ruth, who hardly ever inhaled a sober breath (and died of cancer young because of it) – well, it troubles my sleep.