Several contributors to the comments stream Tuesday noted the distinction between narrative and plot, and they are of course entirely correct on that point. Plot is narrative at its most vulgar, just as the novel constructed entirely around a single character is but a step in the direction of dramatic monolog, that (mostly) dead end of the Victorian era.

Narrative in the purest sense is the unfolding of meaning over time. It moves in the direction of plot to the degree that it becomes figurative, something that can occur in very small increments. This is why (and how, for that matter) a painting can be called narrative simply because it presents a scene. In works of mine that deploy the new sentence, such as Ketjak, Tjanting and many of the sections of The Alphabet, many if not all of the individual sentences can themselves be understood as narratives, often on two & sometimes three levels. First there is an unfolding of meaning in the sentence itself –

A sequence of objects which to him appears to be a caravan of fellaheen, a circus, begins a slow migration to the right vanishing point on the horizon line.

– then there is a frame set up by what comes before and what comes after otherwise “discontinuous” sentences –

The implications of power within the ability to draw a single, vertical straight line. Look at that room filled with fleshy babies. We ate them.

– then, in certain works, individual sentences evolve & elaborate as they reoccur during the course of the work –

A sequence of objects, silhouettes, which to him appears to be a caravan of fellaheen, a circus, dromedaries pulling wagons bearing tiger cages, fringed surreys, tamed ostriches in toy hats, begins a slow migration to the right vanishing point, signified by a palm tree on the horizon.

Bob Perelman was, I think, the first person to observe that in Ketjak sentences themselves function as characters. Indeed, even juxtapositions have a life of their own – the distance between the variation of “The implications of power” that occurs in the final paragraph of Ketjak in The Age of Huts (compleat), which now reads “The power implicit…,” and “We ate them” is four pages, the first on 97, the latter on 101. In Ketjak2: Caravan of Affect, one section of The Alphabet, that distance will double when the book comes out from

All of this is narrative, tho relatively little of it could be associated with plot at the level of the signified, the referential illusion that is realist fiction’s proto-cinematic trope – and which gives way directly to the origin of cinema, so that today a book is judged realist more by how “cinematic” its writing seeks to be than ever was the case in the days of Dreiser and Norris.

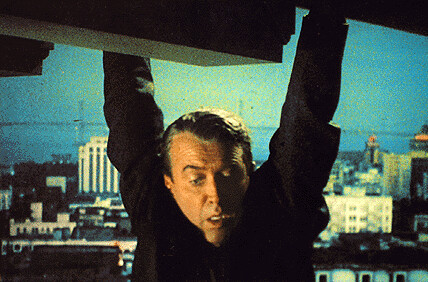

Cinema, of course, can be every bit as sophisticated in its use of such devices – the films of Abigail Child are every bit “as narrative” in this sense as any work of fiction & far more so than your formula chaser, be it James Bond or Jason Bourne. Films like Rear Window or Blow-Up are all about the construction of narratives, and a film like Vertigo kicks it up a notch from there.

Peter Davis makes the point (without using these exact words) that certain poems can today function as a mode of flash fiction. His case in point, Bill Stafford’s “Traveling Through Dark,” tho, sort of the high point of American kitsch, functions not so much as an efficient narrative as it uses plot to set up the arch-silliness of “I thought hard for us all – my only swerving –,” a perfect instance of feigned & posed seriousness & just possibly the single most pompous line ever written. Pomposity figured as caring is in fact a good example of what I meant by the pathological aspects of the

Even a poem like Aram Saroyan’s

has a beginning, middle and end. Engaging the history of typography, it has a social context and makes a point. One might even see in Saroyan’s humor here the same flash of personality one intuits from “I thought hard for us all” (except which poet would you rather spend time talking to at a party?). Strictly as a narrative poem, on the same terms as

My argument would be that these shared levels are only a few of the many pleasures of the Saroyan poem – the play of the letter n as it appears to the mind both before and aft the root m triggers a level not even present in the two sermons. Saroyan’s work is the most complex of the three, and once you realize that, the awkwardness of the others becomes their overwhelming feature.

So, yes, perhaps I should have used the term plot to indicate vulgar narrative on Tuesday. Contemporary poetry is not less narrative today, just less apt to confuse these levels, far more apt to ask the question: narrative to what end?