Singing “

I see where A.O. Scott of The New York Times has listed Murray Lerner’s documentary of Bob Dylan’s performances at the Newport Folk Festival between 1963 & ’65, The Other Side of the Mirror, as one of his critic’s picks for the week, and given it a brief review here. I’ve had the DVD sitting atop my TV set since summer, when I bought it the instant it became available at the ever entrepreneurial bobdylan.com website. I’ve been planning to see I’m Not There, but the only location in

The funny thing is, he’s as changeable here as I suspect he is with six different folks portraying him in the Todd Haynes film. That may be overstating it, but only a little. What it’s really like is that feeling you have when you see some friends maybe once a year and their kids are teenagers – one year they’re kids, the next long and gawky and infinitely awkward & the year after that they seem to be complete adults who tower over their parents. Dylan in The Other Side of the Mirror is only a little older, really, going from the age of 22 in 1963 to 24 in 1965. In the process, he’s not only transformed, but the whole of American pop and folk have as well, dragged along in the wake of his effortless density as a songwriter.

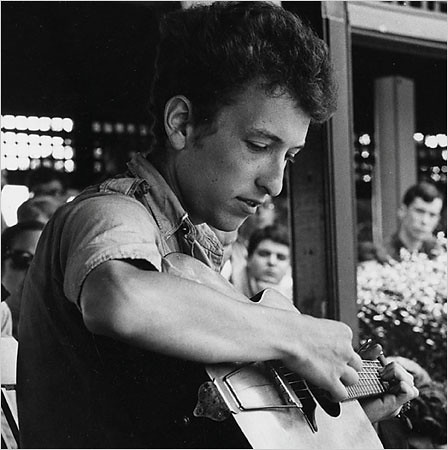

In 1963, Dylan is nervous, humble, earnest, seemingly hyperconscious of the experience & expertise, not to mention talent, surrounding him as he sings “North Country Blues” while Judy Collins, Doc Watson & Clarence Ashley listen intently, merely the most famous of the large crowd attending an afternoon workshop on which they too were probably on the bill. Dylan at this point has already written “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Masters of War,” “Girl from the

By 1964, Dylan is complete a star & conscious of it. The opening scene for that year is of Dylan at the topical song workshop singing – for the first time before a large audience – “Mr. Tambourine Man,” newly penned. You can see Pete Seeger sitting silently, looking down, frowning, trying somehow to fathom what is “topical” about the “jingle-jangle morning” in which “I’ll come following you.” According to Lerner in his interview,

Lerner is incredibly fortunate in that Dylan sang two songs at more than one festival, first “With God on Our Side” in 1963 and 64 – twice in 1963, both times with Joan Baez, the first at the workshop – a version that is widely known and deservedly famous for its appearance on one of the Newport anthology albums that appeared in the 1960s – then in her performance on one of the evening shows. The second is “Tambourine Man,” which Dylan sings only at the workshop in 1964, but reprises in the 1965 concert after he was persuaded to return to the stage and do a couple of acoustic numbers (the other is “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” Dylan’s farewell to Newport) after the raucous crowd reaction to the intense & brilliant – but decidedly paradigm shattering – performance of “Maggie’s Farm” and “Like a Rolling Stone” (another song completely unfamiliar to the crowd, tho it had just been released as a single) with electric versions accompanied by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

Considering its content, it may seem curious that the key element differentiating the performances of “With God on Our Side” is Dylan’s relationship to Baez. At the workshop in 1963, they’re giggly young lovers, she’s the superstar and he’s very much her project – as he was Pete Seeger’s, the two determined to let the world know how good Dylan is and make him famous (be careful what you wish for). At the 1963 evening concert, tho, Dylan & Baez are all business and it’s very straightforward – and it's not as good a performance, frankly, because of this. In 1964, Dylan & Baez have evolved into good friends – you can see his affection in his grin as he looks at her while they sing, really an extraordinary moment given Dylan’s “head down, focus on the song” performance mode that he’s made the hallmark now of a long career.

With “Tambourine Man” in 1964, it’s very much the serious get-through-the-song Dylan onstage at the workshop. (He was, in fact, still carrying the lyrics around in his pocket, as I learned when he sat next to me at a party during that festival and I asked what he was writing – he pulled a thermal photocopy of “Tambourine Man” out of his coat pocket to show me.) In 1965, after very distinct choruses of booing to his electric set, he was coaxed back onstage by Peter Yarrow and had to ask the audience for somebody to throw him an E harmonica – there’s a clatter as dozens hit the stage – and Dylan then gives what I can only describe as the most intimate performance of that song I’ve ever heard.

The politics of the

By 1965, nobody makes any attempt to thwart the gods of audience adulation. Dylan’s workshop appearance has a vast audience and his evening concert closes the festival (as it had in 1963). The ’65 concert is legendary as the moment that folk let rock & roll through the door. In addition to the evening concert, two songs electric, then after he’s talked back onstage, two acoustic, the film also shows Dylan’s afternoon sound check with the Butterfield Blues Band (sans Paul Butterfield, who is visible in a single shot, watching from a distance). Dylan of course used Mike Bloomfield, the best rock guitarist ever not named Hendrix, on the recordings of Highway 61 Revisited, as well as Al Kooper who replaces

Given its controversy at the time, it’s ironic that this live version of “Maggie’s Farm” is the best arrangement & recording that song has ever had. For one thing, the Butterfield Band had a cohesiveness as a unit that The Band (nee The Hawks) never valued. Whereas Dylan’s own arrangements during the entire period up to the enforced hiatus due to the motorcycle accident the following July are effective, if sometimes ethereal, the hard-driving blues sound of the Butterfield Band has often struck me as an opportunity not taken by Dylan, and “Maggie’s Farm” is my evidence for that. It is the

The final element that holds all of this together, curiously, is Peter Yarrow, he of Paul & Mary, who serves as the emcee for all but one of the events Lerner has captured of Dylan. It is Yarrow who says, of the 22-year-old Dylan in 1963, that he has “his pulse on his generation.” It is Yarrow who has to cope with tens of thousands unhappy customers as Dylan completes his 1964 evening concert so that Odetta & Dave Van Ronk don’t get left out. It is Yarrow who beseeches Dylan to come back and do a couple of acoustic numbers in 1965, telling the audience to be patient, “Bobby has to find an acoustic guitar.” It is Yarrow who scolds Dylan & the Butterfield Band that they have to have their settings “down cold” because they won’t have a chance to fix it during the concert. He’s a funny presence, very much the figure of Before as Dylan passes through folk music – more so in this documentary than Pete Seeger, who’s only visible for the finale of “Blowin’ in the Wind” in 1963 and the topical song workshop in ’64. Yarrow’s binding presence is, like Dylan’s repetition of “With God on Our Side” & “Mr. Tambourine Man,” another instance of Murray Lerner’s incredible luck putting together this almost perfect presentation of Dylan’s career as a folk musician. This is one of those works where everything turned out just right.