“The words are my life” is a peculiarly American sentiment. It is what connects Louis Zukofsky, who actually coined this claim, to Walt Whitman as well as to Ezra Pound, as well as to Beverly Dahlen, Rob Fitterman & Rachel Blau DuPlessis, the animating principle that underlies all attempts at the true long poem, or what might more accurately be called the life poem. In

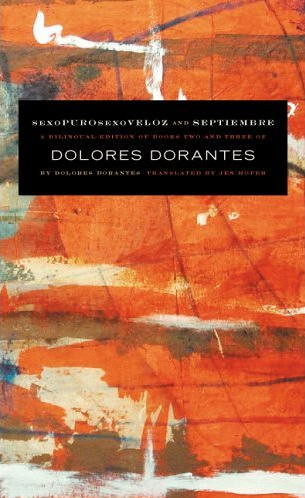

Dolores Dorantes is both the title & author of this work, which in fact consists of two books – SexoPUROsexoVELOZ & Septiembre – that are volumes two & three of this project. (It’s a little unclear if the first volume still exists, having apparently been folded into these texts.) Dorantes’ frame of reference, so far as I can tell, is far removed from North American poetics – I see no concern here with how this might intervene into our poetry discussions, tho she often employs literary devices that will seem familiar to anyone who has read Spring & All or any of the New American Poets: a deft free-verse line; willingness to use the page spatially for rhetorical reasons; a willingness to jump discourses in a single line. Here is one relatively simple passage from the first volume:

COME WITH THE BOATMAN

a madness

– forbidden –

inside you the she-deep you

Beneath a dress

you’ll brandish the sickle

anchor my tide will devour

HTML can’t replicate the small caps of the first line (or maybe it’s that I can’t), but you can see, even here, when it is a continuous voice & perspective throughout that the seven-line passage is filled with shifts marked by letter & punctuation. One might argue (were one a dunce) that the image of woman as ocean is by now a cliché, which it might be were it not for the allegory of the boatman constructed upon it, placed in within a context in which “you” – is that the second person here, or the first person addressing herself? – contains something interior associated both with the sickle (an image both of peasant life & a political party) & its formal kin, the anchor. This passage can be read any number of different ways, all depending on how the reader fills the you in the fourth & sixth lines – make it a man & you have a gender-bending moment, make it a woman & you have an instance of same-sex eros, make it the author & it’s something else again. Make it yourself, well, it could be any one of the above, couldn’t it? Dorantes, the author, has no interest in separating these out for us, which leads to a very particular kind of text, one that is continually in process, never settled.

I would compare the experience of reading her work, especially the first of these two projects, with looking at a mobile, except that one tends to look at mobiles from a stationary position exterior to the process, where Dorantes’ texts feel far more interior & indeterminate & the reader has fewer opportunities to step back & take it all in. Imagine instead a waterslide at a theme park built into and through a giant mobile – then turn the humidity way up. Dolores Dorantes feels more like that.

Septiembre is the more stable of the two works, and here Dorantes can sound at times almost like George Oppen. Imagine this as a section of Of Being Numerous:

The world (before) defending itself

now lies

upon men

They move it

voices moving tides

Without will (the world)

desolate

we carry it ourselves

(in ourselves):

multitude

Like Oppen, Dorantes is a profoundly political poet, tho her own politics feel far from the 1940s Popular Front that was coin of the realm for the Objectivists. Ultimately, tho, any

A word about Jen Hofer’s role here as translator. For many years already, she’s been doing important and powerful work making the poetry of

When Kent Johnson – who along with Forrest Gander has been doing some of this himself – excoriates contemporary (or recent) American poetry for paying too little heed to the project of translation & the literatures of other languages, I have to agree with him, even when I’m the person at whom he’s wagging a finger. I may excuse my own lack of a second language – a single homophonic translation of Rilke does not get me a pass – as a consequence of my working class education (nobody expected me to go college & my own college record sort of shows that), but it doesn’t mean that I don’t also feel this absence as a lack. So, from my perspective, Jen Hofer is all the more valuable, as are Kent & Forrest & anyone else doing this work, because I can’t get to this writing any other way.