You start to realize that Todd Haynes has nailed it, produced something close to a miracle, a reasonably big budget motion picture with A-list players that is as intelligent as its audience, even before you’re through the opening titles to I’m Not There. Very close to the last thing I did in 2007 was finally get together with a number of friends, have a big old Cajun meal at Carmines & head over to the Bryn Mawr Film Institute where the so-called Dylan biopic is finally playing, albeit only at 1:30 in the afternoon & 9:45 at night. Tho the Bryn Mawr, in spite of its collegiate name, tends to skew to boomers, we saw it in a large theater with a sparse crowd – had everyone else see this film downtown? Or is it that the absence of a

It’s not any single shot that convinces you of this at first – tho some of them are stunners, especially the pans of lines at what appear to be homeless shelters or food missions – is that Moondog waiting in line? – as it is the constant shuffle between shots, now in black & white, now in color, this image grainy, that one clear as contemporary cinema can manufacture. Everything you’ve ever heard about six different actors portraying Dylan, not one of them actually named either Dylan or Zimmerman, pales against the realization that this film is not six sequential vignettes, but rather going to be a continual shuffle of all six, from beginning to end, that its fundamental commitment is to keep you off balance from train ride to train ride. That is a brilliant challenge to take on, probably the most difficult thing any director can attempt. The film that follows is not perfect, but it is damn near close enough to keep all its major promises.

I had found myself finally approaching this film with some trepidation – how many times have I heard great things about a film only to be let down by the actual experience itself, which turned out not to be nearly as terrific as the film I’d imagined beforehand? I was almost certain that having heard so many of my friends – and especially my poet friends – rave on about I’m Not There, that I was in for another round of that experience. To my surprise, it was quite the opposite. I’d long ago stopped believing that American cinema could make a film like this – this was a level of complexity only possible in the longpoem – so when I actually began to realize just what Haynes was doing, I had a hard time sitting still in my seat. The last time I was this excited in a theater was probably the opening night for Antonioni’s Blow-Up or Godard’s Weekend, both of which came out 40 years ago. Those films at the time struck me – as does I’m Not There – as miracles, moments when the collaborative process that is a movie has come together to produce something extraordinary.

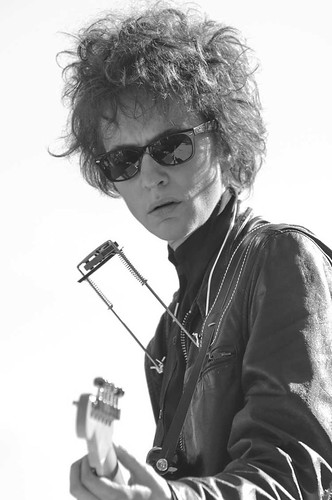

The secret to I’m Not There is simple – everyone knows the story, even down to the bullshit fictions of a childhood that Dylan put out early in his career, so there is no need here to tell it again (indeed, the weakest moments in the film are the few instances where Haynes does feel the need to recreate an historic moment, as such, whether it’s debacle of the civil rights award speech, Dylan the born-again preacher, the reaction to Maggie’s Farm at Newport, which Haynes at least has the sense to satirize – right down to Pete Seeger with the ax – or the fact that Dylan was always credited by the Beatles as being the first one to turn them onto drugs). Instead, I’m Not There most often references, alludes, plays with the details. Thus a twelve-year-old African American who calls himself Woody Guthrie finds himself riding boxcars with hoboes & tells them he’s been writing songs for Carl Perkins & playing backup for Bobby Vee (which in fact Dylan briefly did, Vee’s band being the one post-doo-wop Tin Pan Alley act to come out of the same Midwest North Country as little Bobby Z). It’s a point, like having Guthrie’s motto – This Machine Kills Fascists – scrawled on his guitar case, that makes sense only to a knowing audience (or, much later, Cate Blanchett as the Mighty Jude Quinn, alluding in passing to Brian Jones “and his groovy cover band”).

If you don’t know Bob Dylan, if you don’t know the details of the lore surrounding him, I’m Not There is apt to seem entirely opaque – why is a tarantula crawling across the screen? Why does Blanchett ride a motorbike off screen followed by the sound of a crash & a single (now suddenly in color) image of bike & body covered in the woods? Why do Quinn & Arthur Rimbaud & Jack Rollins seem so completely uncomfortable in their own skins when questioned & prodded by the media? What’s going on here with this paunchy, scraggly, middle-aged Billy the Kid, portrayed by, of all people, former “Sexiest Man in the World” (and one-time Paoli resident) Richard Gere? Most of the reviews – even extremely positive ones like that of Roger Ebert – have seemed at a loss with this sequence in Riddle,

Besides the story that everybody already knows, the other elements that hold this fabulous collage together are (1) Haynes’ sense of rhythm, which he only loses once or twice as scenes carry on too long (cf. the aforementioned Beatles’ appearance in the midst of the too-long run-up to the revelation of a BBC producer – made to look & sound exactly like George Plimpton – as Mr. Jones).; and (2) Cate Blanchett’s ballsy spot-on performance. Because the six Dylan surrogates and their tales are shuffled throughout, Blanchett’s on screen continually from beginning to end. If there ever was any question that she’s the best actor of our generation, this should put it to rest. There isn’t any role for which she wouldn’t be the right performer – she could do Barack Obama, Tony Soprano or Jabba the Hut if she had to, and she’d make a great Tinkerbell. Here you will be shocked to recognize afterwards just how many times her performance made you realize (a) oh yeah, Dylan’s a woman, (b) this really isn’t a guy in this role and, conversely, just how much of the time you were completely oblivious to the question of gender altogether. It’s never really the point Haynes is making, tho he clearly wants us to consider the degree to which Dylan benefits from being in touch with his feminine side (which is why the material confronting Dylan’s unreconstructed sexism – “I love women. Really I do. I think everyone should have one.” – is so important).

Haynes’ strategy makes great sense in trying to tell the story of someone for whom the contradictions are what matter most. I’ve noted before that my favorite part of any motion picture is almost always that period at the beginning where the viewer is being pummeled by details that have not yet gelled into a coherent & increasingly narrow narrative that resolves finally into a chase scene. Haynes has made a motion picture that strives to be entirely composed of opening moments. It’s amazing just how much of this he’s able to do. As the credits began rolling, I said out loud “I could see that again tomorrow.” When the time comes, I’m Not There clearly is a film to buy, rather than just rent.

¹ One of the small surprises of the film is just how much of the singing is Dylan himself, not the recordings of the “sound track” double CD, even tho that turns out to be the best collection of Dylan covers ever assembled.