I’ve been reading Geoffrey Young’s The Riot Act very slowly. It’s one of those delicious books that you never want to end. In one sense, Geoffrey Young is the poet Billy Collins & Ted Kooser both would like to be, writing self-contained works that are narrative marvels and accessible to just about any reader of English. Dig:

Because of You

A few years ago

I charged into each day

for the game of it,

not sweating the past,

not constructing

a future, but today,

because of you,

I want to drive

to Coney Island

in a light snow,

cross the beach

to the water’s edge

and watch the flakes melt

on contact with wet sand.

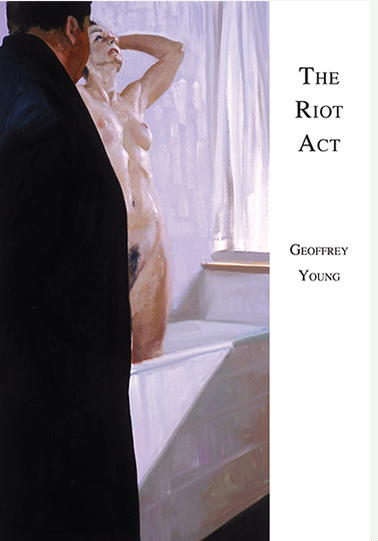

Riot Act is just studded with gems like this sonnet. It’s narrative in the same sense that the Eric Fischl painting on the cover of Geoff’s book could be called narrative, in that the simple juxtaposition of details convey vast worlds beyond themselves. Not only that of Brooklyn, love, of the way values evolve over the course of a life, all framed here against the limitless potential of nature – the ocean, the sky, even the land – but Young manages also to write the kind of poem we might have associated 50 years ago with the likes of David Ignatow, the poem flowing in a single movement to the utter closure of “wet sand,” a noun phrase every bit as soft as the image it presents.

Here’s another sonnet, “Down the Garden Pathology,” which confronts the implications of globalization & climate change:

After great pain a formal

invitation comes to return

to the sidewalks of daily life.

Dishes in the sink await our love

of verismo as fruit flies

await their apotheosis in garbage.

Share-croppers played checkers

with bottle caps; will our unborn

grand-children know orthodontia?

Our islands sink below the reach of satellite?

Each child of privilege shall hold

her guts in hunger, the way

a parking lot looks after rain,

The way they say you lose everything to gain.

The beginning of this poem is a little mysterious. It almost sounds Ashberyesque, not unlike the way much of the rest invokes, to my ear anyway, the work of Jimmy Schuyler – the way the scales tip awkwardly on a phrase like apotheosis in garbage, yet also perfectly poised. Note how the rhyme in the final couplet brings you right back to that same sound in the poem’s initial noun phrase, great pain. Or how that capital T at the head of the last line pulls you away from narrative closer to something like song.

A lot of Young’s poems are like this, contrasting some horrific – yet often unspecified (as tho we’ve agreed not to mention it) – event with the plainest details of daily living. Denial and its consequences – I almost wrote rewards – is an obsessive theme here:

After lies and torture the feds finally order

Lobster and bubbly for the detainees,

Retooling their bricked-in personalities

With freedom’s glaze and lexical radii

As payback for the orange-clad years

Of boredom, sweat and fear. You want

Emergency infusions of allegro juice? You got it.

Justice at last, country-less integers?

Persist, oh captured hard luck cases.

I bow before the cult of your resistance,

Its mission chair. Loose lips install chips.

Bill me for sorcery at the tree factory, Hill.

Historians who dig for truth in Harmsville

Must first breathe the stench of Living Death.

As ironic as that final sentence sounds, coming as it does after a line that slyly invokes both Clintons, at some level it’s absolutely literal. This is the War on Terror viewed as through a David Hockney painting. The mismatch is positively chilling.

It may seem odd that Young, a longtime gallery owner and contemporary art consultant, who lived in

But the move east appears to have been good for him as his writing has developed further into something that is at once reminiscent, say, of first- and second-gen NY School poets while at the same time surprisingly committed – imagine a political Ron Padgett or Bill Berkson tackling the themes of Kafka. The Riot Act comes in three parts, 34 sonnets – the jacket somewhat diffidently calls them faux sonnets, but there’s nothing faux about them – a series of prose works, only one of which extends past the second page, and a final suite of “occasional poems.” I’m not done with this yet and really don’t want to talk about the two final sections. It’s the sonnet sequence that has completely floored me – there are more varied and totally intriguing instances of what this form might be for the 21st century than any other book I can recall. Geoff Young is a sonneteer on a par with Bernadette Mayer or Laynie Browne. Here is, in his thoroughly narrative mode,

Of Wetness

With crayon,

from memory,

a child is trying

to draw the roiling

heave and swell

of whitecaps

in a passage

of choppy waves

while a parent

at twilight

at the kitchen sink

chops onions

dabbing at

unwanted tears.

What strikes me is the degree to which these lines could have come straight from a poem by William Carlos Williams in his Spring & All phase – one of the section’s three epigrams is Williams’ “To me all sonnets say the same thing of no value.” Or consider how Young toys with Valery’s argument against fiction while simultaneously invoking Frank O’Hara in the sequence’s title poem, “Why I Don’t Write Novels”:

A man approaches a closet,

opens the door, reaches in,

selects a shirt, slips it off

the hanger, replaces hanger

on rod, turns from closet

with shirt in hand,

and without shutting closet

door, walks into bathroom,

stands in front of mirror,

puts shirt on, watches

his hands buttoning it, loosens

his belt, tucks shirt into pants,

tightens belt, smiles at

the glass, leaves the room.

There is a calculated austerity here – we don’t know the type or color of the shirt beyond its having buttons, many of the articles are clipped off – “walks into bathroom, / stands in front of mirror, / puts shirt on” – against which the sheer love of narrative construction scrapes. Yes, fiction has to get characters dressed & out the door, but it is true also – as Young shows us here – that poetry can do all these very same things with far greater concision & power. The Riot Act is a fab book and “Why I Don’t Write Novels” is must-read material for anyone interested in the possibilities of sonnet form.