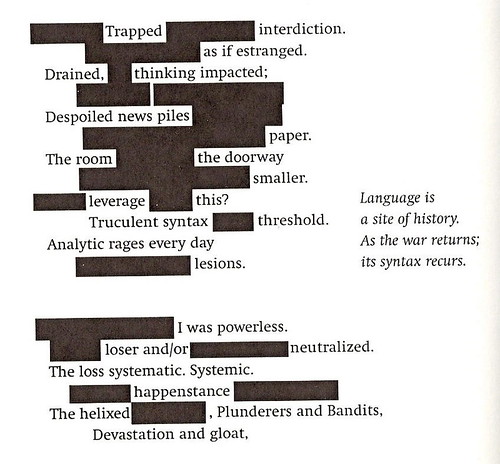

My instantaneous reaction on first seeing Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ Draft 68: Threshold was that it looked very much like my own FBI file. Here are the second and third stanzas:

It does not take much to figure out where the initiating theme of the “unsaid,” the effaced, the “roar of the missing,” which runs consistently through what DuPlessis calls the “line of eleven” of her life poem Drafts, happens to be.

In fact, even before the first redacted line “goes black” in the eighth line of the first stanza, there has been a more subtle erasure:

This what you wanted

When you said you wanted “more”?

The absent term is, whether present or past tense, and which could appear either before or after the initial This is so slight, so apt to be skipped over in our own daily speech, that it’s omission here might not even be felt. It might be below the threshold of recognition.

Plus, the key term in this first sentence, literally the subject, This is not defined, at least not yet. Are we alluding to the text here at hand? A key literary journal of the 1970s? The project that is Drafts? The whole idea of poetry after not just

It is the sixth sentence where suddenly we get the full package of syntax, and it has the feel of water suddenly bursting through a wall or dam¹: You have stumbled across terrain and / Still could not escape this twisted langdscape. That last neologism is, however, a huge (and deliberate) stumbling block. No wonder sentence 7 asks What words? And the eighth, tho it has a final period, feels cut short (again deliberately): Eroded, choked, and stun.

It is here where we get our first black block of redacted text – an entire line’s worth. If it is a single word, it is a long one, since the block takes up the space of 40 letters, indented roughly three (unlike lines 2, 4 & 6, which have all had an indent equivalent to a tab bar: 5 spaces.) The question here is obvious – it’s the same one that I had when I first saw my FBI files some 30 years ago: What’s behind the block?

But, also like my FBI files, which were photocopied from a redacted original, there is no way here really to find out. Unlike, say, Joyce’s Finnegans Wake notebook up in the archives at SUNY Buffalo or the Archimedes Codex in

Which is a detail that has kept me awake at night. There are, I would think, two distinct ways to do this. One is to write actual text, then to block it out so that what remains carries within itself the weight of the missing. The other is the far simpler: the blocks are graphic elements only – there is no real “missing” text. Making it something of a game: is it or isn’t it. And if it is, if there is truly “hidden” writing here, is it something we will confront later, perhaps in Drafts 87 or possibly 106?

It is at the end of this first line of blocked, blacked-out text that DuPlessis writes the sentence that gives rise to the title of this book: You wanted to torque. That is a sentence that can be understood so many ways, from the purely linguistic to the completely erotic. And certainly the text above the redaction suggests something akin to a dreamscape & the psychological. But you ended up here – that may be the most frightening line in all of DuPlessis’ work. I don’t see how it can be read as anything other than an accusation, recalling as it does the opening lines of Dante’s Inferno. What follows is yet another incomplete sentence: Impotent rages locked in these mazes. Five syllables on each side of the caesura – we’re intended to hear the near-rhyme. The next line says what was evident the instant we confronted the look of this page: The page is slowly turning black. Note, however, that here there is no terminal period, because what follows – the last line of the first stanza – is our second moment with these redacted blocks:

My mind immediately wants to plug in the word as into that first block, but frankly I don’t know what to do with the two that end this sentence (note the period!). This is what I think of later in the second stanza (the first of two printed at the top of today’s note) as a truculent syntax threshold. Although, it is worth reminding myself, that’s not what that later phrase says either, exactly.

My point is not to close-read Threshold (tho ultimately I don’t see how you can read DuPlessis any other way) as it is to point to dimensions in the text that reverberate from section to section along the “line of eleven” within the sequence that is Drafts, to suggest just a little what this second direction of reading will get you to. You can see why, in one sense, reading Drafts is an athletic event. There are very few poets who build so much in to an extended text, to write with concision & density that we more often associated with writers of short, compacted texts (early Creeley perhaps, Rae Armantrout) and do so over such a broad expanse – Drafts is 622 pages long, just through number 76. And, as I suggested on Monday, the potential feels limitless. If Drafts is exhausting, it is in the same sense that, say, viewing all of The Godfather is similarly draining, because it engages all of the reader, all of the author, and all of the world.

¹ Recall the six-lined stanzas of the “failed” sestina in Drafts 49: Turns & Turns, an Interpretation.