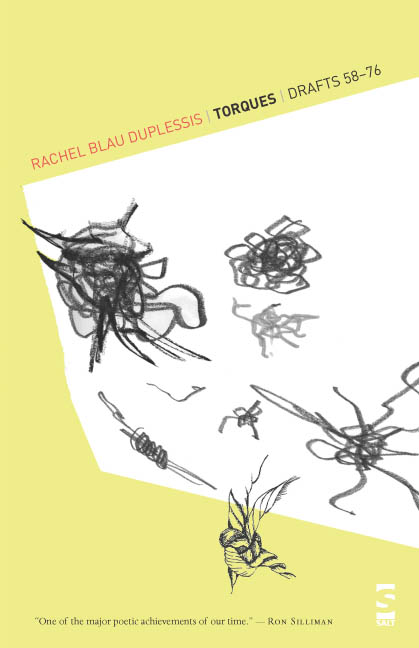

The only thing I’ve ever been able to find “wrong” with Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ marvelous life poem Drafts is the idea that some day it’s going to end, and that day is drawing increasingly near. Torques: Drafts 58-76 incorporates DuPlessis’ fourth pass of 19 poems – there is one “unnumbered” piece that was gathered in her last volume. The plan has been to have six cycles, tho I more than once have argued for more. More than any other text, Drafts has made me understand the difference between the longpoem and the life poem, and I read Drafts, like “A,” like The Cantos, like Bev Dahlen’s A Reading, like my own project, as an instance of the latter.

DuPlessis started Drafts in 1985 & the first two numbers first appeared in Leland Hickman’s great journal, Temblor, two years hence before being collected into a volume entitled Tabula Rosa, published by Peter Ganick’s Potes & Poets Press. I listened to Rachel read from Torques a week or so ago, then sat down with all my DuPlessis books going all the way back to Wells, published as a Montemora Supplement in 1980¹, and Gypsy / Moth, a chapbook that contains two poems from the sequence that makes up the first half or so of Tabula Rosa, “from ‘The ‘History of Poetry.’”

Sometimes the smallest things at, or surrounding, or before, the conscious beginning of a life poem will point you to things you might not notice until much much later. For example, Ezra Pound – a poet DuPlessis has characterized as “haunting” her work – sets up The Cantos so that one numbered section feeds right into the next in a way that is not nearly so sculptural or angled as are the individual sections of Mauberly. You can see Pound actively worrying about this connection right at the start. He ends the first canto with a colon – “So that:” – and ends the second with “And” followed by an ellipsis. It’s a curious step back from the abrupt shifts of Mauberly or those he gave to Eliot’s The Waste Land, and by the time we’ve reached the Van Buren cantos, the sameness from section to section, passage to passage, has begun taking its toll. It took the fall of Italy & Pound’s capture by the U.S. Army to finally shake him loose from this, which explains in part why the Pisan Cantos suddenly feel like such a great forward, even as they were written when Pound himself was almost certainly psychotic, writing on toilet paper in a cage in World War II’s version of Gitmo, awaiting trial for treason.

Happily, DuPlessis has had her own wits about her since Day One. Following Louis Zukofsky’s sense of the part:whole relation in the life poem more than Pound’s, she has characterized Drafts as a “series of autonomous, but interdependent canto-like poems.” But this process of cumulative poetry and of writing through, even writing over other texts – exactly what she refers to here as torquing – is what one finds in both “Writing” and the excerpts from ‘The “History of Poetry.”. Even in Wells, written entirely in the 1970s, we find DuPlessis engaging Grecian figures, the work of Emily Dickinson, the serial forms of George Oppen, offering us in one piece, “Oil,” alternate endings, even as they confront the present & the world (“Oil” is an extended metaphor for menstruation, a topic still not found all that often even in today’s post-feminist verse).

“The ‘History of Poetry’” – note exactly how those quotation marks fall – and “Writing” both read, twenty years later, like rehearsals for Drafts. “’History’” has never been published in its entirety & “Writing,” though it is included in the section of Tabular Rosa entitled “Drafts,” and is mentioned² in the acknowledgements to Drafts 1-38, Toll, has never again been published with it. Personally, I still want to see “The ‘History of Poetry’” complete in its own volume – I have no idea if the missing parts constitute 2 pages or 200 – with perhaps Wells and “Writing” combined in a volume of its own as well. This is because I think DuPlessis is one of the poets whom we need to have entirely available at all times. And I don’t want to wait forty years for the Library of America to figure this out.

It was Robert Duncan & Charles Olson who first recognized that one practical lesson of Ezra Pound’s Cantos was that writing is always also reading, not in the theory-driven fashion one might take from Derrida, but insofar as each of us walks around surrounded by (invaded by) these constellations of articulation that are our educations & literary passions. Not that one needs to get the footnotes – that is almost always the wrong way to read anything – but insofar as these voices whisper to & through us. Both “Writing” & “The ‘History of Poetry’” show DuPlessis wading right into this issue, trying to sort & shake things out. In Drafts she takes what she has learned there & turns with it to confront the world. Which may be why Drafts feels social, even political, overtly so at moments – tho not in the narrow sense of that term – rather than literary. In one way, I’ve always thought that Rachel Blau DuPlessis actually writes the work that Amiri Baraka always talks about writing, but never really does.

So it is no surprise that Torques is a masterpiece. DuPlessis is completely on top of her game & willing to do just about anything if it will further the poem. I find that I read one section and then have to think about it for days before I’m willing to go onto the next – that’s an effect I associate with very few poems – a few sections of “A,” individual sections of The Pisan Cantos, Barrett Watten’s Progress – & more akin to how I feel after a truly major motion picture (Children of Paradise, Weekend, Blow-Up, Pierrot le fou, The Red Desert, Ran). If you read a section of Drafts & it doesn’t completely drain you – and haunt you – you’re just skimming.

More tomorrow.

¹ Available here in PDF format from Duration Press.

² Where it is referred to as the “pre-Drafts work.”