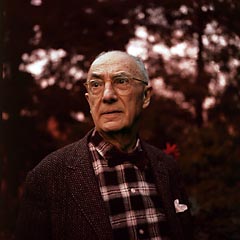

Photo by Jonathan Williams

Somebody who signs him- or herself as Barnes – I have a few cousins with that surname – wrote in yesterday’s comments stream:

"...Jeeze, Doc, I guess it's all right

but what the hell does it mean?"

Aside from the comic way it’s raised, that’s a perfectly legit question. A click on the link in the poem’s title would have brought Barnes, or anyone else, to the full text as I was reading it yesterday morning on the

Narratively, the poem is not that difficult. A man’s lover has departed. He contemplates the residual stain – what my generation has tended to call “the wet spot” tho further on it appears possibly to be some residual semen shining still upon his own “horned branches” – and thinks of her, wondering if he will ever see her again. Or see her again in just this way. The act itself, figured in that stain, makes everything in the world seem far more lucid, even hallucinatory. Williams takes this idea & just runs with it. Some 50 years after this poem was written, people would begin talking of such reactions as “a heightened state of awareness.” It certainly is that.

For a man who made a lifelong reputation for himself as a love poet on the basis of his poems for his wife,

And for a poet who, some 16 or 20 years after this poem was written, would be associated with the neo-Marxian Objectivist poets, and functionally a scientist to a degree that any medical doctor is, Williams is also a writer who greatly trusts the irrational, what I would actually prefer to call, as here, the transrational. Making sense is not one of the critical requirements of verse – indeed it far too often just gets in the way of a much more direct treatment of our feelings & sensations. In the name of Ezra Pound’s only dicta for how to write, “direct treatment of the thing” is very often the exact opposite of treating it objectively.

I love the reiteration here of yellow yellow yellow – that’s the moment when the poem really abandons any literal sense of narrative reality¹ & Williams discusses exactly the impact of this sense and how it transforms the material world. That is the function of this stanza & it seems to me one of the elemental tasks not just of love & sex, but of poetry as well. Poems read with too much concern as to “what the hell does it mean” will always miss at least half of life, maybe much much more.

¹ Why yellow, which is hardly the color of semen? Is it the room, the light at that time of day, the color of the sheets or walls? We’ll never know, but the specificity of the color is as important as the fact that Williams did not write off-white off-white off-white.