Back when mastodons roamed the earth & all television was in black-&-white, I could mosey up to Cody’s Books on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley & find, as part of its poetry section, the current edition of a publication known as the New Directions Annual (NDA). But even more significantly, at least from my perspective this morning, was the fact that I could also find last year’s edition as well, and maybe the year before that. These rather largish collections – NDA ran between 400 & 500 pages – did not disappear the way magazines tend to, the instant the next issue arrived.

In one sense, the New Directions Annual was a remarkable publication. The 1951 issue, to pick one example, included Tennessee Williams, Kenneth Rexroth, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Harold Norse, George Seferis & May Swenson. At that moment, Rexroth would have been the only one with any significant name recognition. The 1942 edition – a bit before my time – advertises Pound & Williams & Kafka as well as Christopher Morley & Katherine Anne Porter. The 1937 edition offers Cocteau, Stein, Williams, Cummings, Henry Miller, and William Saroyan. The 1952 edition: Edward Dahlberg, Ginsberg, Cummings, Kafka, Ashbery. Again: well before the publication of Howl or Some Trees.

By the time I arrived on the scene in the mid-1960s, James Laughlin was getting on in years & his unerring interest in “what’s next” was gradually being eroded by writing that was just an extension of the landmark advances he’d captured in his pages decades before. It’s worth noting that among the thousands of books I own, including the “San Francisco Scene” issue of The Evergreen Review & all the double-issues of Poetry from the 1960s, I don’t today have a single copy of any New Directions Annual. The contributors above are what can be found out from various rare book dealers on the web.

New Directions – the full title was New Directions in Prose and Poetry: An Annual Exhibition Gallery of New and Divergent Trends in Literature – came to mind this week because it was cited as evidence by one of two sets of folks who’ve complained lately that I’ve misallocated their publications in my “recently received” lists – putting both Zoland Poetry and A Sing Economy down as journals, when each is an annual anthology. A Sing Economy is a publication of flim forum, which tries to accentuate the non-journal nature of its annuals by giving each a new name. Last year it was Oh One Arrow.

My first reaction was that, if it were still being published today, New Directions Annual would end up on my journals list as well. It came out periodically – you could set your calendar by it, if not your clock – consisted of almost all new work or new translations, and there was no general principle of editing that you could identify other than an aversion to the School of Quietude. That describes, even to this day, a majority of the journals of poetry in the English language. And NDA wasn’t even restricted to poetry.

If I look at, by way of contrast, a volume like Reginald Shepherd’s Lyric Postmodernisms: An

Anthology of Contemporary Innovative Poetics, just out from Counterpath, it’s immediately clear that this is an anthology. It’s not a periodical, tho in fact Shepherd has edited more than one anthology (and I believe is currently editing another), and if he offered them on a regular basis from the same press, perhaps he could make an annual or biannual out of these projects. It’s immediately clear what the editing principle is. It includes work that has appeared elsewhere previously – the acknowledgements page is a dead give-away – which reinforces both Shepherd’s editing principles and the argument that it’s not a periodical. Indeed, Shepherd reinforces all of this by offering a statement on poetics from each of his contributors.

On any of these counts, neither Zoland Poetry or the different one-shots from flim forum pass muster. This doesn’t make them any less interesting, but it does make them less anthologies. So far as I can tell, the sole grounds on which they would be called such is from a desire to survive on a bookstore shelf longer than a journal, and presumably over by the poetry rather than next to Playboy or Popular Mechanics. Those are not ignoble desires, but they have more to do with the incompetence of bookstore stocking trends than they do the genres these journals would mimic.

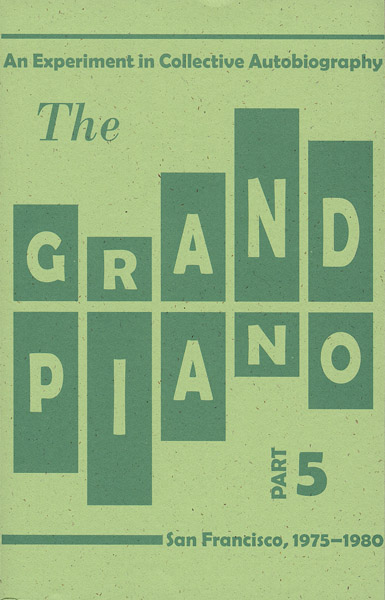

A more complicated case might be The Grand Piano, the series of books being produced on a roughly quarterly basis by a collective of poets, yours truly included, documenting the history of Bay Area language writing in the 1970s. If I use my same criteria – does it appear predictably, does it have a clear editing principle, does it feature work that has appeared before – I get a different skew on the answers. It does appear predictably & in that regard is like a journal, but it has a strong editing principle – each issue has the same ten contributors, each time in a different order – and the work is being written precisely for the book at hand. In this sense, I wouldn’t call any volume of The Grand Piano a journal or an anthology, tho it partakes of some elements of each.

In like manner, there have been journals -- Chain was one, Poetics Journal another – that have focused each issue around a theme. Tho the editors of neither proposed their publications as anthologies, both come closer than either Zoland Poetry or the flim forum one-shots. Their publications demonstrate a strong editing principle above & beyond “what’s new.”

Does this really matter? I think it does in terms of how poetry gets organized on shelves, and also in our heads, and in how (and what) things get preserved. An anthology is always an argument and the book is better the stronger the argument happens to be. I think Shepherd’s volume, for example, is an excellent argument for what I would call Third-Way Poetics in contemporary America, but I also know that Reginald wants to argue against the notion that there is any such thing as third-way poetics – he has a completely different argument, and I think that’s a much more complicated discussion (which I hope to get to before too long). I can’t tell you what the arguments for A Sing Economy or Zoland Poetry are, though there is good work in each publication. What this almost inevitably means, though, is that, if I happen to be around in another 30 years, I almost certainly will still have Lyric Postmodernisms on my shelves, but these annuals will have moved – as journals almost always do for me – into some cartons in the attic.