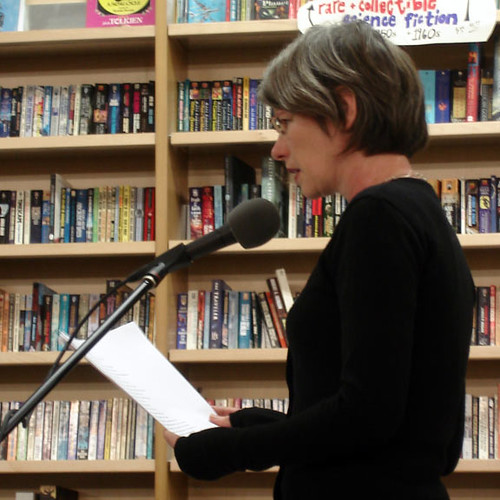

Finally, I got hear Lisa Robertson read for the very first time the other evening. It was one of those events that make perfectly clear just why Robertson has twice finished first – in 2004 & 2006 – as the writer most often cited in Steve Evans’ annual list of writers whose books people are thinking about. Or why the Chicago Review would think to devote a major feature to her work. Not that this was a surprise, really. You can see it in the books plainly enough, such as The Men, which I reviewed here, or Rousseau’s Boat which I reviewed nine months earlier. Or Debbie: An Epic, great scandalous title that that was a decade ago.

Not surprisingly, Robertson is a writer who takes a long time constructing a text. In the Q&A session that followed – one of the best I’ve heard, tho it was short, just because of the depth & candidness of her responses to questions – she indicated that The Men entailed going through work that was already six-years-old and editing out apparently massive amounts of text. She read the very opening & closing passages of this at

This helped to explain to me the discursive tone that Robertson reaches in her work. She loves, as any reader would soon guess, the language of philosophy and her nouns tend to be, as she puts it, “indexical” more than referential:

They elaborate a cogitation. In this way I arrive at the thought of them. Increasingly their oxygen is my own and I in my little coloured shoes to please them. Their revolution is permanent and mine a decoration. When the trees smear their sky, when their poems are the periphery of the West, when they swim from their silver docks, I swim too and we communicate in water. This was September, there were three of us, and one was a man. I feel passionately about their gardens.

This passage, from The Men: A Lyric Book, is not atypical. It’s constructed rather than expressive, although you can sense the politics & bitterness of Robertson’s irony in a sentence like Their revolution was permanent and mine a decoration. Yet it is never clear just how much we should ever take “I” to mean “I” in her work in any literal way. Instead, she likes to accentuate the degree to which things refer to their categories, rather than to a specific instance, by setting them as plurals: their poems, their silver docks. Thus the most referential of sentences – This was September, there were three of us, and one was a man – functions not to clarify the tale so much as to measure just how far from the referential the rest of the language here really is.

This mode of discourse creates an air of distance & Robertson is masterful at controlling just how much & to what ends she chooses to direct it. I imagine that someone might someday spell out a spectrum, not unlike Zukofsky’s “integral” of upper limit song, lower limit speech, only more horizontal, extending from the most aesthetic philosophical discursive mode, say Michael Palmer (or even John Ashbery), to the most social or political, say Barrett Watten. It would be easy enough to place Robertson on that spectrum, much closer to Watten than to Palmer, save that she frames everything in ways that are uniquely feminist from the inside and also distinctly Canadian. Which is to say that her work proposes other axes quite at different angles from this one. To an American ear (and a male one at that), each of these Others can feel like a critique. It’s not that there aren’t American women involved in just this same critique – Carla Harryman, Lyn Hejinian, Bev Dahlen, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Rae Armantrout, Jean Day all immediately jump to mind. Nor that they don’t employ some of the same devices. Or that there aren’t other Canadian poets who don’t likewise explore this territory, such as Jeff Derksen. But there really is only one Lisa Robertson, and we’re very lucky that the number is that high.

PennSound has recordings of three readings by Lisa Robertson here, and A Voice Box has another here.