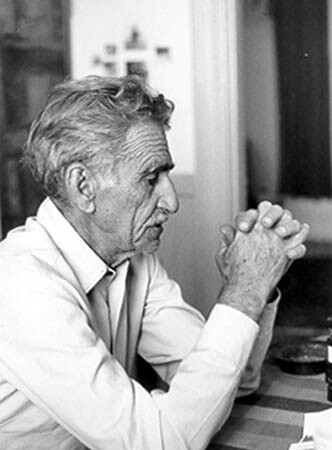

I was somewhere in the vicinity of 20 to 22-years-old when, during an intermission at a marathon antiwar reading at Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco where I was hovering, as was my wont, at the periphery of a crowd that surrounded Robert Duncan, who had just read, when Mark Linenthal, whom I knew from his role as the director of the San Francisco Poetry Center, approached with a granite-faced man and said to Duncan, “Robert, I want you to meet George Oppen.” I can recall also Oppen’s first words to

My second regret, unfortunately not an uncommon one for anyone who was a renter for decades, especially in an area like San Francisco or the East Bay, where one is forever having to balance space & the needs of one’s book collection, is that I no longer appear to possess one of my favorite volumes of that period, four decades ago, a copy of Oppen’s first book, Discrete Series, published not by Oppen himself, but a chapbook reprint done by Ron Caplan out of Cleveland. At a time when everyone I knew seemed to own copies of The Materials, This in Which, and Of Being Numerous, I was just about the only person I knew who owned a copy of that.

I’d acquired my copy of The Materials early on, I don’t know where, almost certainly at Cody’s or Moe’s in Berkeley or (far less likely) City Lights across the Bay. This in Which I’d appropriated, the old five-finger-discount, the first time I’d ever seen a copy, from the university bookstore at UWM, the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, in the summer of 1967. Rochelle Nameroff, my wife at the time, and I couldn’t believe our good fortune. Here was this old Objectivist, actually alive & writing again, producing great work. There are poems there, such as “Street,” as fine as anyone has written:

Ah these are the poor,

These are the poor –

Humiliation,

Hardship . . .

Nor are they very good to each other;

It is not that. I want

An end of poverty

As much as anyone

For the sake of intelligence,

‘The conquest of existence’ –

It has been said, and is true –

And this is the real pain,

Moreover. It is terrible to see the children,

The righteous little girls;

So good, they expect to be so good . . .

Ellipses, as they say, in the original. There are small moments here that I don’t think I fully understood or appreciated as a young man, the doubleness created by “An end of poverty,” rather than the more standard preposition to. Or the reiteration in that last line, which at the time I might have read as sentiment rather than the certainty of horror. Or that most curious of words, Moreover, concluding the longest of this poem’s disjointed, half-broken sentences. This is a poem that works precisely in all the ways its syntax appears not to.

But the poems of Discrete Series, composed between 1929 & 1934, spoke to me then, as they do to me now, with a directness I find nowhere else in Oppen’s work. It’s not simply that they were the poems of someone in his early twenties, the same age I was when I came upon that volume at Serendipity Books in

Thus

Hides the

Parts – the prudery

Of Frigidaire, of

Soda-jerking –

Thus

Above the

Plane of lunch, of wives

Removes itself

(As soda-jerking from

the private act

Of

Cracking eggs);

big-Business

This poem operates like a tiny Moebius strip in that the dangling final noun-phrase big-Business is precisely that which “Hides the // Parts – the prudery / Of Frigidaire.” There is, in any consumer business, including one as simple as a lunch counter, a radical gap between that which is customer-facing & that which is not. This dissociation between public & private is paralleled by that alienation that transforms any “private act” into labor for pay. Thus if the gaps of “Street” stand for just how good those righteous little girls won’t be soon enough, and how and why, the vertigo of sheer terror, the unmarked ellipses of this earlier poem stand for processes no less brutal, but hardly inevitable. Only one of these exists in a world in which political action is even conceivable.

I will always be an advocate for the earliest Oppen. Far from the unrealized works of a beginning writer, they show us the poems of an optimist, someone who has not yet adjusted to the permanent defeat that was Stalinism. The later work, at least through Of Being Numerous, is no less luminous, but its relationship to the world is chastened, perhaps even depressed. This of course leads to my last regret – those twenty-five years between poems.

ж ж ж

A Celebration of

George Oppen’s 100th Birthday

100 minutes of talk & poetry

Hosted by Rachel Blau DuPlessis & Thomas Devaney

& featuring

Stephen Cope, George Economou, Al Filreis,

Michael Heller, Ann Lauterbach, Tom Mandel,

Bob Perelman, & Ron Silliman

Today, April 7

3805