The “bad girl” in the arts is not new, but it has had a new lease on life in & around poetry & performance art since Kathy Acker – who rarely acknowledged the degree to which her novels functioned as part of the poetry scene – rewrote so many of the rules 35 years ago. Karen Finley, Leslie Dick, Dodie Bellamy, Tracy Emin, to name just four, have all demonstrated very different ways of being transgressive, especially around issues of the body & sexuality, in the years since.

Chelsey Minnis adds her name to the roster with a volume that wants to be outrageous, Bad Bad, from Fence Press. It’s a complicated project and one that demands the writer put herself out there for all pretty much to see. But it’s not, in the usual sense, a “difficult literature” – one can, in fact, plow right through the book.

I read Bad Bad three times in the process of judging the William Carlos Williams Award earlier this year and it joins that list books that I was unhappy I couldn’t give some kind of prize to, because it’s really very good. But reading it again after a couple of months hiatus, I find myself noticing its limitations more. This is a terrific book, yes, but it could have been a devastating one, and there’s a difference. And on a fourth reading it starts to show up.

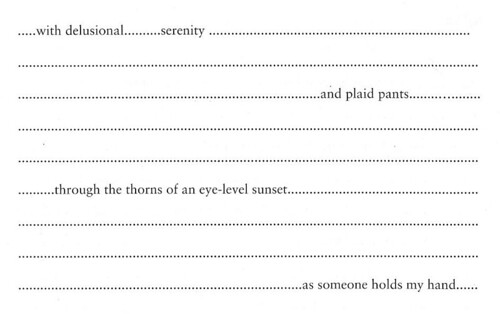

Essentially Bad Bad consists of three types of work. First, thirty pages of prose-poem prefaces, a total of 68. Then a series of nine poems that would actually be very airy, just a few lines scattered around the page were it not for many rows of dots connecting them almost into a prose structure. And then finally some poems in a relatively conventional format. Each section is noticeably weaker than the one preceding it. Reading the book, I’m convinced that this is intentional – it’s part of the larger set of transgressions. But as a reader of the book, I’m not convinced that this is the best strategy. Like a lot of “uncreative” poetry from the conceptualists, this is actually more interesting to think about than it is to read.

But the prefaces here, on the other hand, are simply glorious. Here is “Preface 30,” my personal favorite. All of the ellipses are in the original:

Once I became a poet I could not be taught to be a poet…

It is like wearing a slit slip under a slit skirt…

Now I am careless of my statements…

And it feels good…like a champagne bidet…

I should not have poetry as a vanity and I should not have it as a career…

But I should have it!...like a doorknob covered with honey…

I would love to read the book for which that truly was the preface, but this is not that book. You can hear the pout of the narrator, half valley girl, half Eurotrash ingénue. At the same time there is, in almost every line, some remarkable observation. That first sentence is, as anyone who’s been around the scene for awhile will recognize, exactly on target.

The second section is roughly seventy pages long, but contains considerably less in the way of words than the prefaces. Not atypical is the following, picked pretty much at random:

The dots really do transform the text. The sensation is not unlike the experience of reading Ronald Johnson’s redaction of crossed-out original. This is very much a denial of blank space as a field, as those periods are intensely linear. In other places, it’s worth noting, they don’t go all the way to the right margin, and they cluster or spread out.

Underneath all this speckled energy, very much the same kind of persona emerges, totally irritating, totally charming. But it’s really in the final section, fifteen moderately conventional post-avant poems (one is a time-line), that the role of persona is most deeply underscored here. And my association in those poems was not with Kathy Acker at all, but with somebody completely different albeit from the same generation, the late Darrell Gray, especially of the Philippe Mignon poems, more satiric & less subtle than Kent Johnson’s more recent heteronyms.

At one level, this is all quite good. But on another, Minnis doesn’t quite pull the trigger – this is a work that cries out to be outrageous, but after Kathy Acker or Dodie Bellamy or the films of Carolee Schneeman¹ actually fucking her boyfriend of 30+ years ago, Minnis’ sort of kiss-and-tell hints about an unnamed mentor come over ultimately as coy.

But this fits with the book’s downward spiral structure, its use of truly dreadful headline fonts (see the cover above, readable enough at the 180 points – or whatever it is – there, but genuinely inhuman at 12 points in the “Prefaces”), not to mention the choice of pink – a Jeff Koons sort of “bad bad” – for the cover, rather than the black with a dog collar aesthetic of an Acker. Cheesy, instead of sleazy.

I think there are all kinds of questions here about how much of this is in Minnis’ control. Maybe all of it, but if you believe in the persona & equate it with the author, maybe not so much. And a lot of what you think about this book will probably depend on how you answer that question. After four times through, I find myself with different answers on different occasions. I don’t know that this means I’m getting closer to “the truth.” That remains elusive.

¹ Schneeman was never a “bad girl” that I can tell since she has always lacked the one thing that binds all the bad ones together – a sense of shame, some concept of all this being somehow dirty. Hers truly is a sex-positive position, with no sense of what Sianne Ngai calls Ugly Feelings. It’s interesting to contrast how Acker relies on this framework of social (and self-) condemnation whereas a later writer, such as Dodie Bellamy, is far more playful with these borders, able to evoke & examine but not be ruled by them.