The city of

Sweet God, it is lonely to be dead. Sweet Good, is there any God to worship? Sweet God, you stand in

Now Emily Dickinson is floating down the

This 1956 poem by Jack Spicer, which first appeared in The Poker, no. 5, in the winter of 2005, is taking on something of a promiscuous history. It appears in the current issue of The Massachusetts Review, devoted to GLBT writing, and is reprinted, with credit to the Mass Review, in the current edition of Harpers (subscription definitely required). Both, being

One can only imagine what Jack Spicer would have made of an appearance in Harpers, at least once he’d stopped puking his guts out. The cosmic joke at the heart of Book of Magazine Verse, the volume that was in press when Spicer died at the age of 40 in 1965, is that none of the magazines for which this diffident, supremely geo-centric author “wrote” his poems would ever have deigned to print them.

Not only did Spicer proleptically assume automatic rejection by The St. Louis Sporting News (now just The Sporting News) and Down Beat, two publications that didn’t (and still don’t) normally print poetry, but also by Ramparts, the SF-based Catholic theological journal that, in the 1960s, transformed itself into a radical antiwar publication (Mother Jones is a pretty direct descendent of Ramparts), Poetry – which by 1965 was regularly publishing Louis Zukofsky, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley &, most pointedly from Spicer’s perspective, Robert Duncan – and The Nation (whose poetry editor at the time, Denise Levertov, Spicer despised as she did him¹), but even an emergent post-avant mimeo rag such as Vancouver’s Tish and the apparently non-existent Vancouver Festival.

Spicer was very protective of his outsider status. He would allow his mimeo magazine J to be distributed as far east as

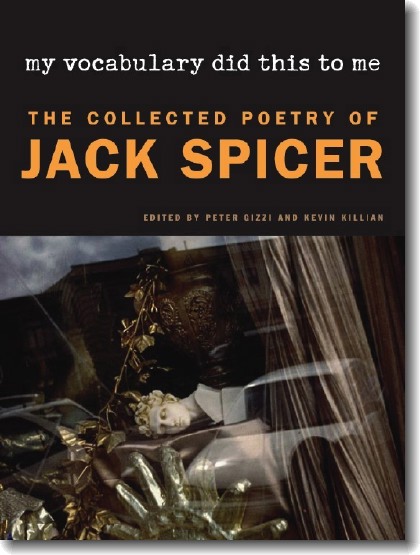

In the past several months, tho, works by Spicer have turned up in both Poetry and The Nation, part of the run-up to the publication next month of My Vocabulary Did This To Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer, edited by Kevin Killian and Peter Gizzi. Having seen the manuscript at different stages of editing, I can say without hesitation that this is one of the great books of the 20th and of the 21st centuries. Gizzi & Killian have done

a tremendous job.

Still, it is very strange to see Jack Spicer’s poetry turn up in places where it never would have done so in his own lifetime.²

§

Today’s Philadelphia Inquirer has a feature on the city’s Car Share program entitled – in 80-point type on the front of the Magazine section of the paper – “Drive, They Said.” Is this the largest print in which an allusion to Robert Creeley has ever appeared? And who at the Inky besides editor John Timpane & book reviewer Carlin Romano will even recognize it as such?

¹ Spicer appears to have seen her as a homophobic bluenose, an enemy of poetry. She seems to have seen him as a racist alcoholic. The fact that, in the mid-1960s, she was still something of an acolyte of Robert Duncan’s certainly did not help.

² I believe Spicer did send his poems both to Poetry and The Nation, both of which, true to his expectations, rejected them.