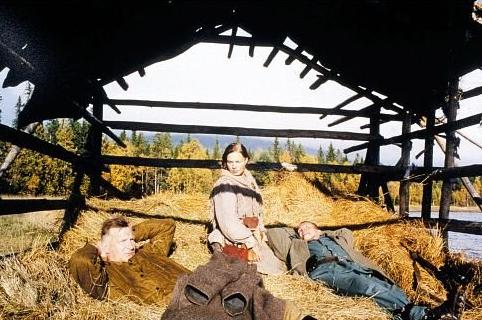

L-R: Viktor Bychkov, Anni-Kristiina Juuso & Ville Haapasalo star in the 2002 film Cuckoo

A couple of weeks ago I saw a film that I have not been able to get out of my head. Two of the other foreign films I’ve seen lately have been by the director Fatih Akin, German by birth but Turkish by heritage, a subject that films like Head On and The Edge of Heaven tackle with great insight. I’d read something somewhere that wondered, since the

Yet the film that’s been haunting me isn’t either of Akin’s, tho I’d recommend them both. Instead, it’s a little Russian comedy called Cuckoo, filmed in 2002 by Aleksandr Rogozhkin, something

The set-up is fairly simple. It’s 1944, the last days of World War 2, and a Finnish sniper is being punished by his comrades, essentially sentenced to death. They’ve set him up for a suicide mission, chained him to a gigantic boulder, dressed him in a German uniform, and left him there to starve, or be eaten, or possibly shot or bombed as he’s more or less out in the open, unprotected save for a rifle that he uses only for its telescope. In theory he’s supposed to shoot as many Russians as he can before they shoot him. At roughly the same time, and not so far away, the Russian army has ferreted out a subversive and is sending him back to the main battalion and hence back to

At which point he is found by a young Lapp woman who literally drags him back to her nomadic encampment where she nurses him back to health with some reindeer soup made from milk & blood – there’s a great scene of milking the reindeer. A member of the last nomadic tribe in

It becomes one once he’s finally free and makes his way down to the encampment. He presumes the wounded Russian is militantly anti-Finn, the Russian presumes he’s a fascist – the Finn actually understands the implication of the word “fascisti” but can’t make the Russian understand that he’s not. The word “democracy,” or at least its Finnish equivalent, is not in the Russian’s vocabulary. Yelling out the names of anti-war novels (War and Peace, For Whom the

Much of the rest of this film is watching the three characters develop relationships without understanding one another’s language. They talk to one another as if they’re being understood, but the listener invariably hears only what he or she wants to hear, and responds accordingly. They keep this up for over an hour. It’s a brilliant, even stunning tour de force.

This may sound like a very thin premise on which to build a motion picture, but it’s not a one-joke trick so much as a meditation on language, expectation and interpretation. I suspect that this film works best if you know one – but only one – of the three languages, tho my own feeble Russian vocabulary – never more than a hundred words to begin with – has eroded over the years, so it would be more accurate to say that I understand the sound of Russian more than I do the language. Sámi, on the other hand, sounds unlike either Finnish – which it is related to – or Russian. The script is carefully written, although I wonder if the jokes that come cross in English subtitles work quite the same way listening to this film in any of its three primary languages. For example, Rogozhkin, who wrote as well as directed the film, never allowed Anni-Kristiina Juuso, his Lapp star, to see the entire script (which was in Russian), instead giving Juuso her lines in Finnish – she’s a Lapp radio broadcaster in addition to her acting – who then translated them herself into Sámi.¹ A fair amount of the cognitive dissonance between the three gets muted – or I presume that it must – when one is reading subtitles all in one language. Is it really the same film? The broader acts of cultural misconnection – as when the Finn builds a sauna that the other two find useless, or when he tries to explain to the Russian that he studied philosophy in college and wanted to be a poet but lacked the talent – work much better in the context of the film than they do writing them out here.

I won’t explain how this film turns out – there are major plot twists and serious risks involved, not to mention a long mystical sequence when Anni wolfishly attempts to howl one of the characters back to life by blowing in his ear – other than to note that the rules of comedy prevail. Tho in the end, when you see the officer marching back to Stalin’s Russia in 1945, rather than to, say, south to Helsinki, you have to wonder if he has done any more than to delay the doom that awaits him.

In some sense, this is a film intended to be viewed by foreigners. Not in the way that a French flick with Juliet Binoche is targeted at the American market, but rather because it positions each of us unalterably as foreigners. If we can’t get all of it, it teases us with the possibility that we didn’t get any of it. Subtitles only complicate the problem.

You can imagine Wittgenstein just loving this film. This is, after all, something of his later vision of the problem of language. Just because we speak and write the same tongue, I think you can understand what I’m writing here. And you think you understand what I’m saying. Yet I know I have readers who profoundly don’t get it, or who get it exactly wrong. And I know that just because I’ve never – not once in over 40 years – been able to finish a poem by Richard Wilbur or Mark Strand without nodding off doesn’t mean that this is necessarily the only conceivable response to their writing. But the people who gush over such work might as well be Martians. It’s impossible to know exactly how to value what they’re saying, when what they say seems to be so totally against the evidence of this grey, bloodless conformity. Yet I was struck, moved even, by Kirby Olson’s confession in the comments stream the other day that he doesn’t “get” poetry that’s not funny – that closes off maybe 80 percent of literature, something he’s actually paid a salary to teach. And it explains why the poets he does value, even at their best, lack subtlety. The chromatic changes of a Larry Eigner poem are, for me, sometimes as intensely beautiful as a clear summer sky. And there’s nobody I’ve ever read, not even Dickinson, who comes close to Eigner’s ability to make statements of great complexity appear utterly simple.

Cuckoo does a great job of showing how people who can’t possibly communicate actually do get things done, not so much in spite of it all as through it all. A lot like an Eigner poem, it feels pretty simple when you watch it. But if you’re like me, you’ll be playing it over in your mind weeks & weeks later.

¹ I’ve been told – tho I have no way to judge the validity of this – that most Finns have never met a Sámi speaker. It’s true that there are just 20,000 Sámi who speak nine different related languages, tho