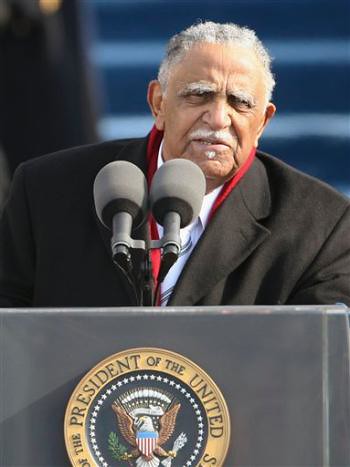

There were three instances of poetry during the inauguration of Barack Obama: the anointed inaugural poem by Elizabeth Alexander, and then two different parts of the closing benediction by Rev. Joseph Lowery: the opening, which quoted, sans attribution, James Weldon Johnson’s great “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” sometimes referred to as the “Negro National Anthem,” and then again at the end, when Lowery, the 87-year-old civil rights hero who co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with his friend & collaborator, Martin Luther King, in 1957, pulled a moment seemingly out of the history both of the black church and do-wop dee jays¹, with

we ask you to help us work for that day when black will not be asked to get in back, when brown can stick around ... when yellow will be mellow ... when the red man can get ahead, man; and when white will embrace what is right.

It’s conceivable that this also is a quote, from the work of Muhammad Ali.

At the one inaugural party we attended later in the day – really more of a “Get outa town, George Bush” affair – I found that the suburban progressives of Chester County had not recognized the Johnson quote and were divided on Lowery’s later contribution, depending on whether or not they thought that humor was appropriate for an inauguration. (It was my favorite moment of the whole inauguration, if that tells you anything.) One school counselor told me that her high school only gets one “news” channel, Fox, and that Fox’s Talking Heads chatted over Alexander, making the poem impossible to hear. Others who had heard it found the poem “nice,” but uninspiring. I was repeatedly asked who Alexander was, answering that she’d taught with Obama at the

One of my sons, tho, who has heard quite a bit more poetry than most of my suburban friends, was more interested in Alexander’s stilted delivery which paused. After. Every. Word. He wanted to know if Alexander had had a stroke. I had to explain to him that there is a kind of poetry in which writers do read. Like. That. It’s intended, I added, to underscore the thoughtfulness and urgency of the poem. “Shouldn’t the text do that?” he asked. I didn’t have an answer for that, at least beyond my Cheshire-like grin.

¹ One can almost hear Jerry Blavat, “the Geator with the Heator, the Boss with the Hot Sauce,” saying these lines.