A quick note here in response to something Curtis Faville wrote in the comments stream to the links list of January 29:

Funny no one has mentioned [Larry] Fagin and [Clark] Coolidge's On The Pumice of Morons, their parody of Maya Angelou's 1993 Inaugural Poem for Bill Clinton's first term.

Surely no one has written a worse poem–

"Take it into the palms of your hands,

Mold it into the shape of your most

Private need"

Is one of my favorite worst lines. Tee-hee.

Why has no one else "risen" to the occasion to parodize this latest most pedestrian effort by the fake officialdom of literature?

Ignoring for the moment the question of whether parodize is what happens to the verb parody when it goes to

But the second (and far more important) is that Alexander’s place in poetry is nowhere remotely akin to that of Maya Angelou, and that Alexander’s poem reflects none of the pomposity that left Angelou open to an attack such as that ventured by Fagin & Coolidge. I’ve heard complaints over the years that On the Pumice of Morons was racist and/or sexist – I don’t think it was the former. Fagin & Coolidge’s real crime lay in making excessive sport of someone who had already made herself ridiculous in public.

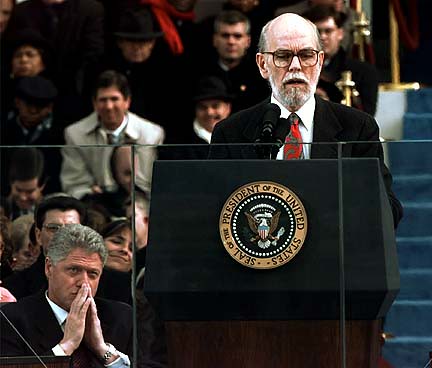

Nobody took such liberties with Miller Williams after his inaugural poem for Clinton’s second term:

Of History and Hope

We have memorized

how it was born and who we have been and where.

In ceremonies and silence we say the words,

telling the stories, singing the old songs.

We like the places they take us. Mostly we do.

The great and all the anonymous dead are there.

We know the sound of all the sounds we brought.

The rich taste of it is on our tongues.

But where are we going to be, and why, and who?

The disenfranchised dead want to know.

We mean to be the people we meant to be,

to keep on going where we meant to go.

But how do we fashion the future? Who can say how

except in the minds of those who will call it Now?

The children. The children.

And how does our garden grow?

With waving hands – oh, rarely in a row –

and flowering faces. And brambles, that we can no longer allow.

Who were many people coming together

cannot become one people falling apart.

Who dreamed for every child an even chance

cannot let luck alone turn doorknobs or not.

Whose law was never so much of the hand as the head

cannot let chaos make its way to the heart.

Who have seen learning struggle from teacher to child

cannot let ignorance spread itself like rot.

We know what we have done and what we have said,

and how we have grown, degree by slow degree,

believing ourselves toward all we have tried to become –

just and compassionate, equal, able, and free.

All this in the hands of children, eyes already set

on a land we never can visit – it isn't there yet –

but looking through their eyes, we can see

what our long gift to them may come to be.

If we can truly remember, they will not forget.

I challenge anyone to think of a worse line than The disenfranchised dead want to know.

But Lucinda’s dad has always been someone who took his quietism seriously. A much more diligent formalist than the poem here (And how does our garden grow?) might suggest, Williams has stuck with the same mid-tier college publishers he’s been with his entire career. There were no parodies of this timeless epic perhaps because it took care of the job itself. And there was no real target. By 1993, Angelou had been receiving the usual trade press prize nominations – National Book Award, Pulitzer – for over 20 years. Not so Williams, tho he was at least Angelou’s equivalent in experience. And not so, Alexander.

The other dramatic difference between Angelou in 1993 & Williams four years later & Elizabeth Alexander’s experience this past month has to do with the changes in communication that have taken place since the mid-1990s. Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning” predates even the Buffalo Poetics List, the first serious attempt at a listserv for poets just then starting to come online with email, by over ten months. While Tim Berners-Lee had written the code for the first World Wide Web server in 1990, the first true browser, NCSA’s Mosaic, wasn’t released until the middle of 1993.

I don’t think that any of us – not even the worst acolytes of futurephilia – entirely appreciates what happened there. When Angelou read her piece on television in 1993, it accorded her a concentrated boost of media exposure that had been unheard of in American poetry since, at least, Robert Lowell’s face on the cover of Time magazine in 1964. The only way Fagin & Coolidge could respond was via a chapbook, with its belated arrival & dodgy distribution. Against the one-time millions who saw Angelou on television, and the somewhat smaller number who ultimately purchased the Random House edition of On the Pulse of Morning, Fagin & Coolidge had a response that figured at best in the hundreds. As that link to Angelou’s edition notes, there are at least 30 copies of that puppy floating around used book emporia some 16 years later. Abebooks turns up nada, zero, zip for On a Pumice of Morons.

Within five days of the inauguration, I was able to post Elizabeth Alexander’s video from her appearance on the Colbert Report. Where response to Angelou’s poem was constrained by access to existing media – I’m unaware of any “the empress has no clothes” reviews in such midcult venues as the New York Review of Books – which left it to Fagin & Coolidge & copies sold at the counter at such shops as City Lights, Moe’s & Cody’s to note the cloying mawkishness, Alexander’s poem – arguably the best one ever read at an inauguration, regardless of its limitations & her profoundly inauthentic reading style – was critiqued & put down from a wide range of positions almost immediately.

One of the issues confronting all mainstream media in 2009 is precisely an inability to control access to commentary. Just as the rise of cable has gutted broadcast television, the rise of the net is having a direct impact on institutions – trade publishers, bookstores, libraries, newspapers – that have all been complicit with regards to the question of concentration of resources. Do-it-yourself commentary fundamentally changes the equation. While this presents issues for younger poets – how to construct an audience being the obvious one – it also presents profound opportunities.

I noted here the other day that Arielle Greenberg & Rachel Zucker’s Starting Today website, with its 100 poems for the first 100 days of the Obama administration, almost exactly duplicates Stephen Vincent’s parallel project, Omens from the Flight of Birds, for the first 101 days of the Carter regime in 1976. Both projects are, I suspect, fraught with the same difficulties – I dare Cornelius Eady not to cringe at the sight of his own sloppy sentimentality in a quarter century, regardless how praiseworthy the notion – but it makes infinitely more sense, time-wise, distribution-wise, and ultimately project-wise, to do this on the web. That isn’t going to help Eady or Alexander any, but it will change what we do in the long run, and the ways that we do it. Just having access to every inaugural poem since Robert Frost shuffled his around & recited one that Kennedy had requested (and that Frost remembered) rather than the one he’d written ought to give future sacrificial poets pause for thought.