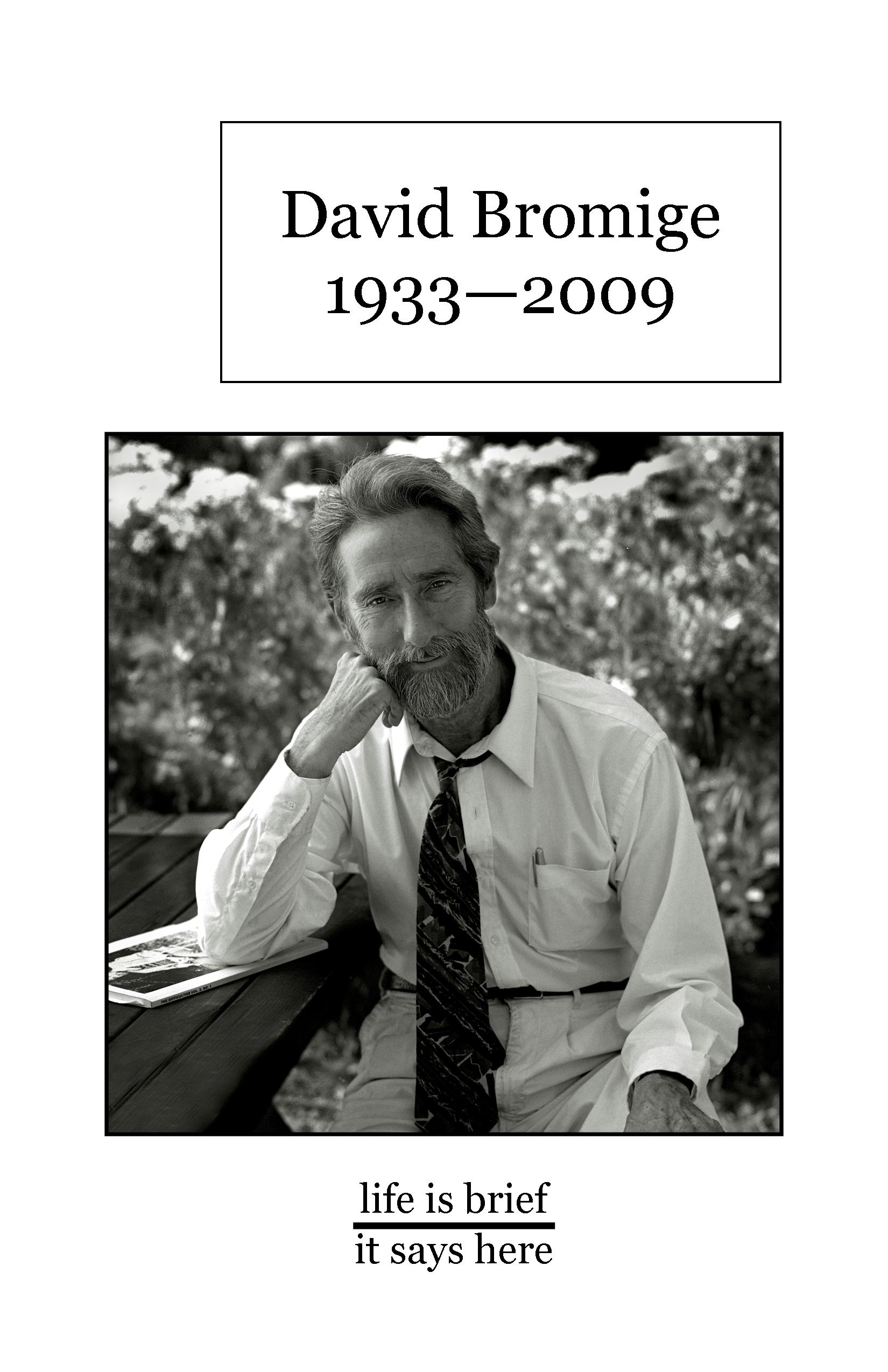

In the 14 years and two months since we – my wife, my then-three-year-old sons & I – first moved to Pennsylvania, there have really been just two moments when it felt like hell to be so distant from the Bay Area. The first occurred early in 1996, still in the depths of our first real winter here, when Larry Eigner died. The second will be this Sunday, when there will be a memorial service for David Bromige at Ragle Ranch Park in Sebastapol from 1:00 to 4:30 pm (further details, with map, behind that link).

David was like an older brother to me, tho looking at those dates above I realize that he is closer to my parents’ age – six years younger than my dad, seven than my mother – than he is to mine. There is nothing I have written in the 41 years since I first met him that doesn’t have some tinge of his influence about it somewhere, even to my use of ampersands or the spelling of tho at the beginning of this paragraph, a last nod to what I once heard David call Robert Duncan Spelling, tho Duncan got it from Pound as Pound did from Blake, etc., an acknowledgement of the changeable and personal dimensions of language. And of a heritage that reaches back centuries, to the days when Shaxberd cld spell his name any way he damn pleased. Or pleas’d. Or pleasd.

When the first issue of This came out in 1971, David had already published six books. David never once played the “I’m the older poet” card with us youngsters, and if he could easily have garnered more fame had he just stayed what he had been in his youth – the heir apparent to whole SF Renaissance scene – he moved on from that with no sign of a second thought. His first appearance in This, in its third issues in 1972, was a far cry from the circuitous sentences & magesterial line breaks that had characterized his earlier books. Instead, he presented a series of six works from a larger (and I believe otherwise unpublished) project called “Homage to N. Rosenthal.” One piece was a single word: prettier. Two others were works of a single line, including the epic Get off my tits. One was a couplet as complex & mysterious as any two-line work I’ve ever read:

light work but

dear materials

You have to hear how that couplet opens & closes around the liquids of the two els that bracket this work to appreciate just how fine David’s ear could be. At one level, this poem might be read as being “about” writing, but at another, deeper level, it’s a celebration of the a sounds in its second line. Nor is the vowel sequence of the first – i, o, u – any less exquisite. Ditto the way hard consonants shut each one-syllable word of the first line, yet appear just twice – at the opening of dear and within materials.¹ David makes this look / sound effortless, but clearly it’s not. It’s a compression of formal detail at a level of force a new formalist, so-called, couldn’t even imagine. Just two years after Melnick & I weren’t sufficiently courageous to gamble on Robert Grenier in the Chicago Review, this couplet shows that David’s not only reading Grenier, but thoroughly gets it, to a degree that would take some of us (me, for example) several years still.

I think David held his relationship to what was soon to be known as language poetry every bit as lightly he did his relation to the New American Poetry. What was interesting about this new work evolving in San Francisco interested him; whatever he found tedious, was easily ignored. When his doctoral committee at Berkeley balked at the first draft of his dissertation – it wasn’t sufficiently tailored to the MLA idea of prose – David decided that it was the degree itself that was unnecessary. He had what he needed to stay at Sonoma State & he’d done the thinking that was the actual core of the project. The rest ultimately was unimportant. As I think the many statements that can be read at the David Bromige website his son Chris has put up make clear, teaching for David was really about his students. He showed no interest in using the position to build a power base or an institution.

David had two gifts that stuck with him throughout his life. First, he had the best sense of the tension between line or linebreak & the sentence of any writer I have read. He might have learned this from Duncan, Creeley & Olson, but it was something he took deeper than any of his masters. Which may be why, when he started producing the little prose poems of Tight Corners & What’s Around Them, many of his devoted readers gasped. For the master of the line to forego his most powerful tool underscored just how serious he was about moving on as a poet.

Bromige’s second gift was that he was the finest reader I’ve ever heard. His voice, a warm baritone, combined with an accent that held equal measures of his childhood in Britain, his young adulthood in British Columbia & his life as an American. As I told Carolyn Jones of the Chronicle the other day, listening to David gave you a sense of what Dickens might have sounded like as a post-avant poet. But a Dickens tempered with the likes of Louis Dudek, Fred Wah, Robert Creeley & just possibly some American noir slang as well. You can hear a number of his East Coast readings on PennSound, but for me the archetypal Bromige events were always the ones in the Bay Area where David might know as much as 75% of the audience personally. David’s give & take with the audience between poems was as much a part of his presence as the poems themselves. All I have to do to hear David at his best, is just to think of them – they’re quite etched in my imagination, going all the way back to the reading at the Albany Public Library in 1968 where I first heard David, reading with Harvey Bialy & introduced by Paul Mariah. David Perry, a Bard grad & acolyte of Robert Kelly who was a fellow student of mine at San Francisco State, had coaxed me out to that event so that I could hear Bialy, who was fine. But it was the other reader, with this not quite British, not quite placeable accent, with this resonant voice & fine wit, who flat out blew me away. 41 years later, that remains one of the most eventful readings in my life.²

So this Sunday, starting at 1:00 PM Pacific Time, I will be turning my heart & my thoughts toward Sebastapol & toward the great gift that was David Bromige and to the people who loved him.

¹ Really at the start of the second syllable, a “soft” echo of the d in dear, the t serves almost as a pause to set up the flourish of the couplet’s final phonemes.

² Hitchhiking on my way home afterward that night, I got a ride with another of the event’s attendees, one David Melnick, who has likewise turned into a lifelong friend & influence.