During his life, I knew Jason Shinder only by his anthologies – Eternal Light: Grandparent Poems, Divided Light: Father and Son Poems, First Light: Mother and Son Poems, The Poem I Turn To: Actors and Directors Present Poetry That Inspires Them, Birthday Poems: A Celebration – and by his work with the YMCA, a niche quietist writing program that likes to pretend it’s diverse & confuses pompous with prestigious. At least in conversation, I’ve used the anthologies to explain why I don’t contribute to theme-based collections, even when well intentioned.¹ These collections, which promise to foreground sentiment in the most mawkish manner, represent everything about the School of Quietude I find cringe-worthy. They remind me that underneath every Grant Wood-style heartwarming American portrait lies a Ted Nugent-esque wingnut with a semiautomatic in the gun rack. And they remind me why Clement Greenberg felt it so important to oppose kitsch in his critical writing – precisely because it represented fascism with a human face.

Which is to say that I was unaware that Shinder had been Allen Ginsberg’s assistant. When Howl: The Poem that Changed the World came out, edited by Shinder, I thumbed through it, didn’t think it was especially well done even if I half-subscribed to book’s basic premise, and didn’t buy it. It never occurred to me that its editor was this same Jason Shinder I had seen in these other contexts.

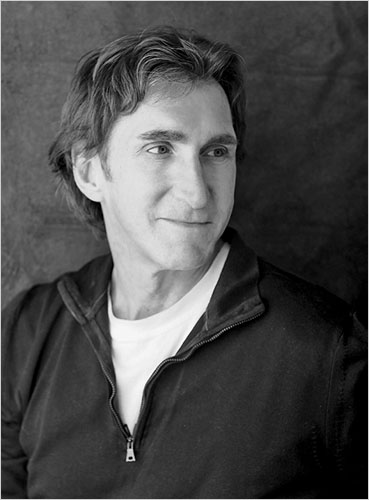

So that when I opened Stupid Hope, Shinder’s posthumous collection lovingly edited by four friends – Sophie Cabot Black, Lucie Brock-Broido, Tony Hoagland & Marie Howe – I was completely unprepared for what I was about to find:

Afterwards

I remember the shame I felt after the news

of the illness that I was not as lovable

as I thought. I must have done something

wrong. And then

I was content in my disappointment

which kept me alone. It was a kind of courage

that allowed me to go on without comfort.

It was a kind of beauty when there was no one

I wanted near.

Or

Poetry

What I am saying is not my true condition.

And what do I do if I am but am not?

I have my own life but it is not persuasive to me.

What she was doing, there was no way to remember it.

I can never find a color I love.

I believe I will love but get the day wrong.

I don’t do what my friends say I do.

These are spare, unflinching, brilliant poems, utterly without sentiment. Or maybe not without sentiment, but understanding it in a new way, as the tonal cover we extend to loss so that it is not too horrible to look at.

Winter

If I could stop hoping for a month,

stop praying for a month, I could be alone again

with God in the old way, in a room at the end

of a hall and ask why it gets late early now.

Shinder’s poems transcend their SoQ roots, I think, for the same reason that Rae Armantrout’s acts of linguistic vertigo can make it into The New Yorker. The poems are so pared down that readers who do not come to them with the same set of shared assumptions about poetry don’t get bogged down in the trappings of their larger social context. Would I feel the same way about Shinder’s earlier books, all published by houses like Indiana and Sheepmeadow, presses to which I pay almost no attention? I really have no idea. Facing one’s own death – especially as Shinder did in the poems – can have a profound impact on how one conducts one’s art. But Shinder suffered with the cancer that finally killed him for at least a dozen years. Possibly he’s one of those quietists – like Wendell Berry & Jack Gilbert – who has always been worth reading. I don’t know. But I intend to find out.

¹ Short version: it’s the wrong way to read poetry. It’s precisely where the “news” in poetry is not. Such anthologies always discredit whatever theme they seek to advance, whether it’s anti-war poetry or works about third cousins twice removed.